The Commander-in-Tweet Isn’t Just Disrespectful, He’s Dangerous

Trump’s defenders say that his tweets are aimed at his base. Too bad the rest of the world reads them, too.

Three presidential administrations have had ownership of America’s longest war. President George W. Bush invaded Afghanistan in October 2001 after the Taliban refused to oust al Qaeda, the terrorist group responsible for the 9/11 attacks, in a manner that suited him. He then shifted the Pentagon’s focus two-and-a-half years later by ordering the invasion of Iraq, which allowed the Taliban to reverse the gains made by coalition forces during the first phase of the war. President Obama—who’d campaigned on a plank that there was a “bad” war and a “good” war—pulled U.S. forces out of Iraq while surging the number in Afghanistan. But by the end of his time in office, along with ordering the SEAL mission that resulted in the killing of Osama bin Laden, the head of al Qaeda, he’d lowered the troop level from a high-water mark of 140,000 to 9,000, using the claim that the hard-won reduction in Taliban-led violence against the central government would now allow Afghan forces to oversee to Afghanistan’s security.

Then, in spite of the fact that during one of the Republican debates his fellow candidate Jeb Bush told him he couldn’t insult his way to the presidency, Donald J. Trump did just that. Candidate Trump’s national defense message from the stump had basically been that “we don’t know how to win anymore” and he knew more about the threat than the generals did. Once in office, his first acts as commander-in-chief were to take credit for a Pentagon multi-year airplane contract that had been finalized during the Obama administration and to publicly blame military leaders for an ill-fated special operations raid in Yemen.

The three-and-a-half years that followed have demonstrated that President Trump is out of his depth when trying to lead the U.S. military. Instead of productively addressing NATO’s funding inequities, he tried to bully America’s treaty partners, most visibly at a summit in Brussels where the schoolyard dynamic was on full display, cliques and all. This unprecedented tension with our allies was against a backdrop of equally unprecedented statements where the president of the United States told the world that he’d fallen in love with North Korea’s brutal dictator and that he believed the Russian president’s claim that that country had nothing to do with American election interference in spite of the findings of multiple U.S. intelligence agencies to the contrary.

Then, President Trump pushed for the creation of the Space Force, a redundant branch of the U.S. military that will do little more against actual threats to the homeland than create new budget pressures in what are bound to be fiscally challenging years ahead. He spent $5.4 million for a new and non-traditional military parade on the Fourth of July after being wowed by the Bastille Day celebration while on an official visit to France. And more than once, the president has expressed a belief that the F-35 is invisible—not just stealthy but actually invisible.

On the military personnel front, “all the best generals”—as Trump labeled Mattis, McMaster, Kelly—have one by one left his administration, each in his own way frustrated by the president’s impulsiveness and inability to focus on details critical to national security. Mattis resigned in a letter that is arguably the most literary take-this-job-and-shove-it statement in the history of American government. Trump, never one to accept being bested in any way, told the White House Press Corps that he’d “essentially fired [Mattis]” and some months later called him “the world’s most overrated general.” Mattis responded by quipping at a formal dinner in New York that Trump had also called actress Meryl Streep overrated, so he was happy to be the “Meryl Streep of generals” because “at least we’ve had some victories”—a biting reference to Trump’s tweet about pulling troops out of Syria that caused Mattis to resign in the first place because he felt the move would hand the country over to ISIS.

Overall, Trump has shown through his speeches, press conferences, and tweets that his understanding of the military is not fully formed, as if he never gave the subject much thought in the sixty-some years since the Saturday mornings in the late 1950s when his parents dropped him off at the Lowes Valencia in Queens for war movie matinees. That’s the only way to explain the president of the United States making a statement like this: “When I took over, it was a mess. . . . One of our generals came in to see me and he said, ‘Sir, we don’t have ammunition.’ I said, ‘That’s a terrible thing you just said.’ He said, ‘We don’t have ammunition.’ Now we have more ammunition than we’ve ever had.” That line is pure Audie Murphy in To Hell and Back and fatally simplistic in an era where the principal threats to our forces are things like hypersonic weapons. (And any general who framed an actual inventory problem like that would be laughed out of the E-Ring by his fellow four-stars.)

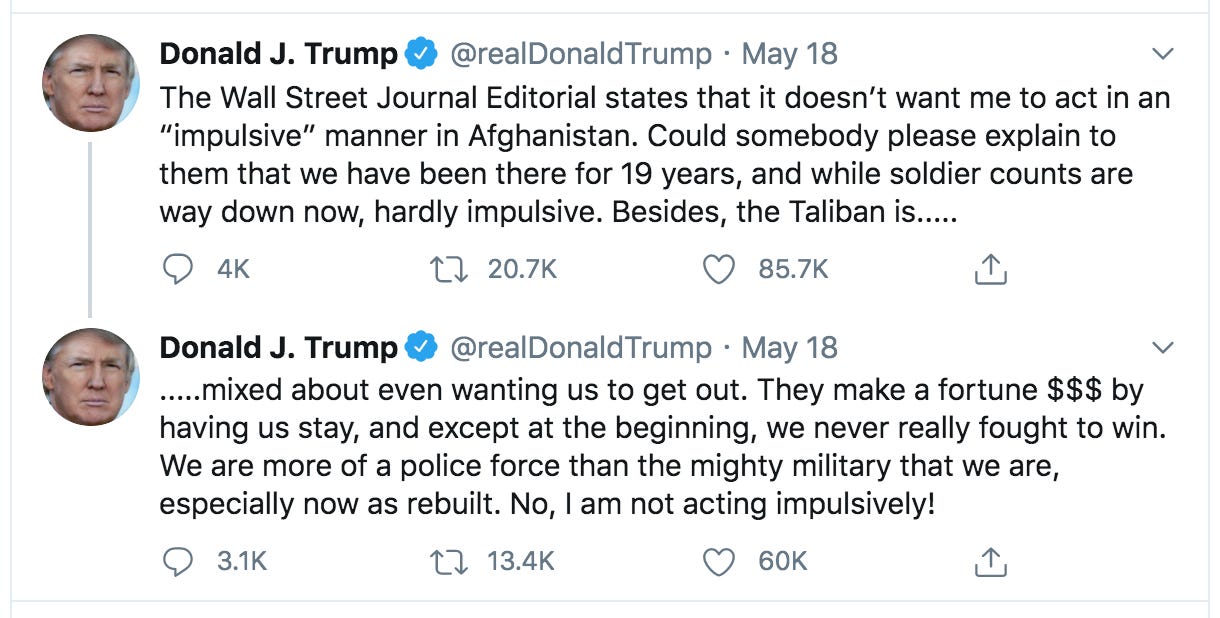

Most recently, President Trump tweeted this:

Never mind the self-own of the president denying he’s impulsive by tweeting the claim he’s not, what he wrote here is both insulting to veterans of the war and should be concerning to Americans at large.

For a guy who brags how much loves and supports the troops, the tacit statement he makes when he writes “we never really fought to win,” regardless if his intent is to simply slam previous administrations, is that those who gave their all in carrying out the missions they were assigned in Afghanistan wasted their time or gave their lives in vain. That’s a reckless tone for a commander-in-chief, who could well need the best and brightest to answer his call to man the all-volunteer military without hesitation, to strike in a chaotic world.

Hundreds of thousands of American service members have served honorably in Afghanistan, and they deserve defter analysis from their president than what Trump offers here. I saw the war firsthand as a journalist embedded with the U.S. Army’s Task Force Rakkasan in 2010. During that time, as I walked through the villages and rode along during air assaults and lived in the austere outposts in Paktika Province near the Pakistan border, I gained a full appreciation for the work American troops were doing there at that time. As well as keeping insurgents neutralized and away from trade routes and other areas of commerce, they shaped the attitudes of the locals by fixing the cell phone towers and handing out prayer rugs to shepherds and facilitating meetings of the tribal elders (known as shuras) in order that they might discuss subjects like how to get their girls into school for the first time and where to establish polling stations for the national election.

Which leads to the second major problem with this tweet combo beyond disrespecting our military veterans: The current commander-in-chief apparently lacks a basic conception of how military power might be proportionally applied in certain situations. When Trump makes the claim that we never fought to win in Afghanistan “except at the beginning” he ignores that the beginning of Operation Enduring Freedom (quickly changed at the outset from the religiously insensitive “Operation Infinite Justice”) wasn’t a 21st-century version of D-Day. The “invasion” was several dozen CIA caseworkers and Green Beret joining forces with Afghan warlords on horseback supported by a single carrier air wing based in the North Arabian Sea.

Of course, Trump is the same guy who, during a Department of Defense presentation about the need to recapitalize our aging nuclear weapons inventory, reportedly asked—in all seriousness—why we have nukes if we’re not going to use them, creating the impression on the briefers that the concept of deterrence was lost on him. (Remember when he was stumped by then-critic Hugh Hewitt over the nuclear triad? Simpler times.) So too, presumably, are surgical applications of our “mighty military” like counterinsurgency operations, no-fly zones, tanker escorts, and freedom of navigation missions.

None of this is a categorical defense of how the war in Afghanistan has been conducted over the long haul. As the Washington Post exposed in its “Afghanistan Papers” series last year, over the 19 years we’ve been there, a lot of the time our military leaders had little to no confidence that we’d be able to accomplish our national objectives in spite of their public testimony to the contrary. So, if Trump had tweeted, “Unlike my predecessors, I will not commit American forces overseas without a defined end state” I’d find less to fault him over. (While we are on the subject of definition, what are U.S. troops doing on our southern border again? And remind me what the Trump administration is negotiating as the terms for our exit from Afghanistan? So. Much. Winning.)

Trump’s defenders say that his tweets are aimed at his base, but, to our collective national embarrassment, the rest of the world reads them too. And it doesn't overstate the threat to worry aloud that his intellectual sloth and lack of precision in the words he chooses while addressing defense matters emboldens our enemies, both nation-state and independent actors. At first, they thought he was ballsy and crazy enough to act on his not-so-veiled threats about how big his button is and how he could end wars very quickly (read “nuclear option”) if he wanted to. But now they see that he’s just a functional illiterate with a short attention span.

That’s dangerous. Already Russia, China, Iran, and a resurgent Taliban are testing American resolve with greater frequency in places like the skies over the Baltic, the waters of the South China Sea and the Strait of Hormuz, and the streets of Kabul, even in the middle of a global pandemic. With each ridiculous tweet they fear us less.