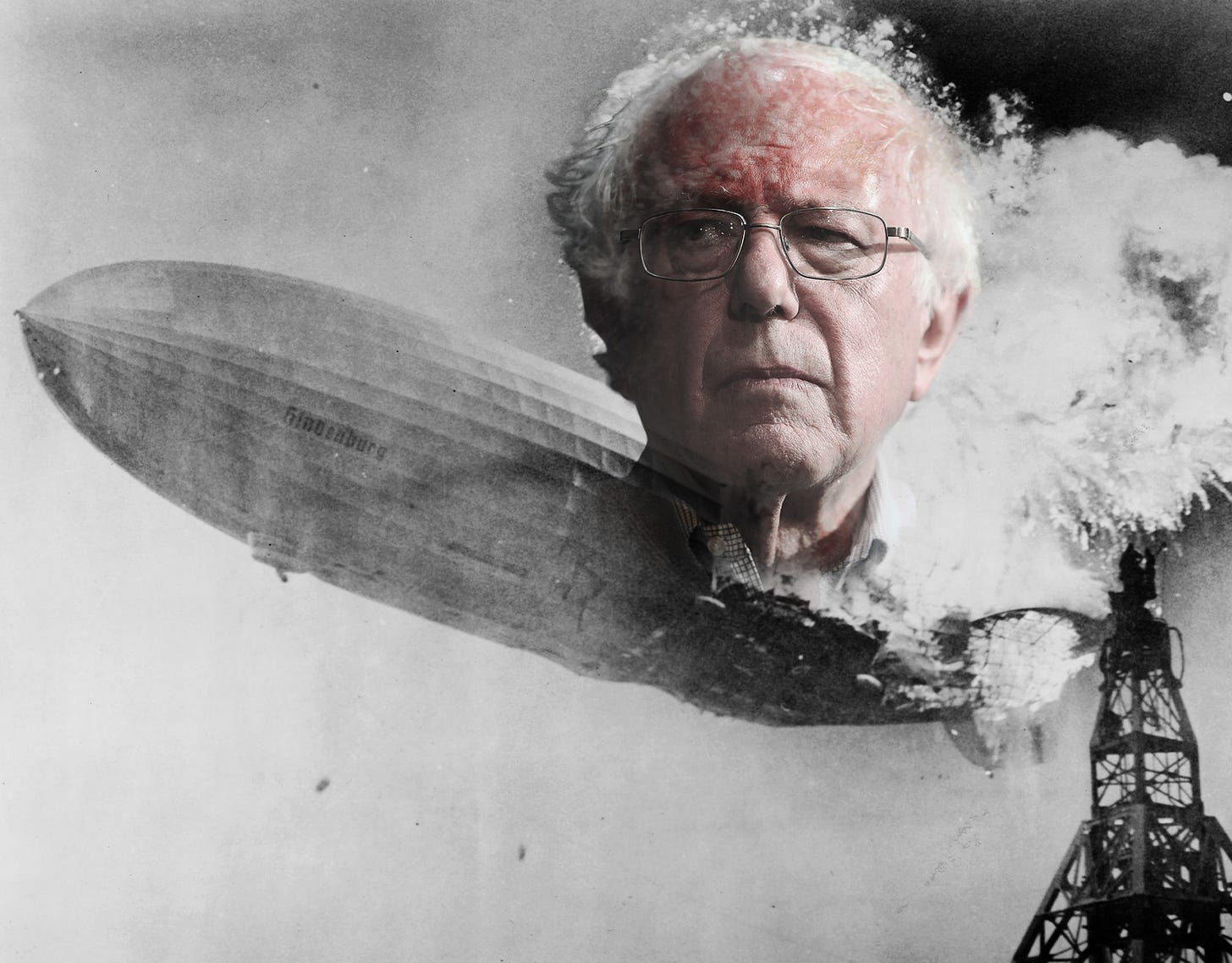

This Is How Trump Would Destroy Bernie Sanders

Bernie is Trump's dream candidate.

He's back—with a vengeance.

Bernie Sanders is having yet another political moment, this time the result of a belated realization that his 2020 campaign is sturdier and more strategically balanced than the insurrection of 2016—auguring trench warfare through the primaries all the way to the convention.

He is, in short, the Democrats' waking nightmare: Sanders remains more likely to split the party than win its nomination. And in the unlikely event that he does, Democrats would then be tethered to the candidate of Donald Trump's most ardent dreams.

The elements are in place for Sanders to persist: He has a coalition of ideologues, working-class voters, and young people who despise our political and economic inequities. He enjoys the support of zealous advocacy groups. He deftly uses litmus tests of purity to outflank Elizabeth Warren on the Democratic left. And he has a cult-style group of hardcore supporters for whom no one else will do.

Sanders has fortified these strengths by becoming a better and smarter candidate. His rebound from a heart attack rallied his followers while imbuing him with a newfound residue of amiability. He has sharpened his attacks on Joe Biden over trade deals, the Wall Street bailout, Social Security and the Iraq war. Schooled by his shortfall in 2016, he is aggressively courting minority voters.

Sanders’ most conspicuous success is among Latinos: He has been seeding primary states with Hispanic staffers; assiduously connecting with Hispanic media and grassroots organizations; and targeting Hispanic voters in states such as California, Colorado, and Texas—all of which threatens Joe Biden's purchase on the Latino vote. And among African-Americans, polls show a growing acceptance of Sanders as a prospective nominee.

Bernie 2.0 is running so well in the first three primary states—Iowa, New Hampshire, and Nevada—that it is possible, if not likely, that in this fractured field he could win them all. In the fourth, South Carolina, he appears poised to finish second to Biden. By the end of February we could see a de facto Biden-Sanders race.

Beyond that, his staggering grassroots fundraising should propel him through the Super Tuesday states and then deep into the rest of the calendar. He has pockets of strength in battleground states such as Michigan and Wisconsin. On the stump and in debates, Sanders is built to last. He translates as authentic because he is: It's easy to remember what you've believed without surcease for roughly half a century.

But that's where Sanders hits the wall: ideology.

Sanders is America's least supple politician, captive to an unyielding inner vision which brooks no compromise. His candidacy is rooted in the unwavering belief that America is about to awaken to the rightness of his unwavering beliefs.

Take the crowd-pleasing title of his major campaign address: "How Democratic Socialism Is the Only Way to Defeat Oligarchy and Authoritarianism." Here self-solemnity meets opacity, the instinct to hector rather than seduce.

Sanders "democratic socialism" is not the socialism of Karl Marx. Rather, it is a dramatic expansion of the New Deal, spurred not by a Great Depression, but by Sanders view of a comprehensively unjust America plummeting toward plutocracy. In itself, this indictment of the status quo is grounded in observable realities: a concentration of wealth at the top; millions of Americans living an unplanned misfortune away from economic devastation; life expectancies defined by economic disparity; increasingly powerful corporations operating with too little oversight; the accelerating consolidation of political power in the hands of the wealthy few.

Thus, in the abstract, one can appreciate Sanders' idealistic specification of the "basic economic rights" which he argues are due every American:

The right to quality healthcare. . . . As much education as one needs to succeed in our society . . . A good job that pays a living wage . . . Affordable housing . . . A secure retirement . . . A clean environment.

The problem lies in the enormous gulf between saying and doing, political romance and legislative achievement. Rather than deal with the harsh realities of our politically, geographically, and demographically polarized society, Sanders imagines igniting a "political revolution" which sweeps all before him.

As he told the New York Times editorial board:

[That] means being an administration unprecedented, certainly in the modern history of this country, maybe going back to FDR. Maybe even beyond FDR. So, to me, what my administration is about is not sitting with Mitch [McConnell] in the Oval Office . . . negotiating something. It is rallying the American people behind an agenda that they already support. All right? This is, I think, what makes me a little bit different than other candidates, and that is not only will I be a commander-in-chief, I will be organizer-in- chief.

This turbocharged populist presidency, he continues, will stampede the previously adamantine Republican majority leader into compliance: "That's how change comes about: you make an offer to Mitch McConnell that he cannot refuse, and that is that the American people want to move in a different direction."

Put more starkly, Sanders proposes to effect this sea change by summoning from scratch a movement unprecedented in our political history: a permanent mass mobilization of a militant majority of voters—most of whom were previously passive observers—reanimated as unremitting progressive political activists bent on compelling a recalcitrant Congress to enact the Sanders agenda through an exponential expansion of governmental power.

The anti-gravitational grandiosity of this vision raises fundamental questions about its honesty and practicability, the danger that inflamed expectations will breed further alienation and, not least, Sanders' own grasp of observable reality.

But the most basic question is whether the nuts and bolts of his agenda would fuel his promised political revolution or, more prosaically, even help eke out a victory in November.

Take his signature proposal, single-payer healthcare. A poll conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 60 percent of swing voters in the pivotal states of Michigan, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin consider it a "bad idea." Other polls consistently show that most Americans favor protecting their access to private insurance—including working people happy with the coverage their unions fought to secure. One wonders whether Sanders envisions using a general election campaign to undertake their reeducation.

Further, Americans of many stripes are endemically dubious about the quality and responsiveness of government programs. Having suffered the ministrations of their local Bureau of Motor Vehicles, they imagine standing in line, literally and figuratively, to receive mediocre healthcare.

Then there is cost. Asked about this, Sanders has said "I don't give a number and I'll tell you why: it's such a large number and so complicated that if I gave a number you and 50 other people would go through it say, 'Oh…'”

Instead, Sanders argues generally that all but the wealthy would save more—by abolishing premiums, copayments, and deductibles—than they would pay in increased taxes. But Sanders rarely mentions the failure of his home state of Vermont to enact a single-payer program—precisely because no one in either party could figure out how to pay for it. Come September, Trump would not be quite so reticent.

A candidate less doctrinaire than Sanders would appreciate that Republicans have gift wrapped this issue by attempting to abolish Obamacare and, with it, popular protections such as coverage for pre-existing conditions. All Democrats need do is give Americans a choice between private insurance and Medicare for those who want it. The alternative is electoral malpractice—a self-inflicted debate mired in charges that the Democrats are narrowing choice and raising taxes. Which is exactly what Bernie promises his nominal party.

This goes to another Achilles heel that Republicans have yet to exploit, but will: the daunting overall cost of Sanders' political revolution could double the federal budget. Working with Sanders’ own website, experts project an increase in spending far greater than that required by FDR'S New Deal or Lyndon Johnson's Great Society—roughly $60 trillion over 10 years.

Such an explosion in spending requires a massive increase in the federal deficit and/or significant tax increases on the middle class. Mark Zandi of Moody's Analytics estimates that the taxes on the wealthy proposed by Sanders cover only between 40 percent and 45 percent of his programs. The rest would be paid, directly or indirectly, by Americans at large.

Imagine, if you will, Sanders trying to explain to ordinary citizens why all this is good for them. And then try to envision them rushing to the political barricades, en masse, to support it.

To the contrary, Sanders’ enthusiasm for doubling the size of government feeds the perception that he is driven more by an ideological passion for federal power than a targeted desire to help Americans most in need.

For example, Sanders proposes to provide free public college for every applicant, no matter how wealthy, and eradicate $16 trillion in student debt—irrespective of the borrower's ability to repay. These proposals are not only gratuitously expensive but regressive: squandering taxpayer dollars on free college for the affluent threatens to short change programs for those who truly need them—whether working parents in search of adequate childcare, or unemployed workers who require job retraining.

For all but those impassioned with grand governmental designs, maximalist federal programs are not a good in themselves. And when excessive or ill designed, they diminish the credibility of those who propose them.

This applies doubly to a candidate who, heedless of impact, insists on calling himself a socialist. While less off-putting to young people, the label is anathema to the swing voters Democrats need. An annual Gallup poll shows that the percentage of Americans with a positive view of socialism hover in the mid-30s; a more recent survey by the Hill found that 76 percent of respondents would not support a "socialist" candidate.

No doubt Trump will use the rubric freely—and dishonestly. But Sanders' singular passion for the word, and the programs to match, would unduly help Trump hamstring Democrats in November.

All of which is why, according to the New York Times, "Trump's advisors see . . . Sanders as their ideal Democratic opponent in November and have been doing what they can to elevate his profile and bolster his chances of winning the Iowa caucuses." They seek to build Sanders up now so that, come autumn, they can pivot to accusations that Sanders is a candidate gripped by the desire to plunge America into freedom- throttling socialism—and worse.

A week after the 2016 election, Kurt Eichenwald of Newsweek noted that, of strategic necessity, Hillary Clinton had treated Sanders with extreme gentility. Trump would not have been so kind, Eichenwald continued:

So what would have happened when Sanders hit a real opponent, someone who did not care about alienating the young college voters in his base? I have seen the opposition book assembled by Republicans for Sanders, and it was brutal. The Republicans would have torn him apart. And while Sanders supporters might delude themselves into believing that they could have defended him against all this, there is a name for politicians who play defense all the time: losers.

Here are a few tastes of what was in store for Sanders, straight out of the Republican playbook. He thinks rape is A-OK. In 1972, when he was 31, Sanders wrote a fictitious essay in which he described a woman enjoying being raped by three men. Yes, there is an explanation for it—a long, complicated one, just like the one that would make clear why the Clinton emails story was nonsense. And we all know how well that worked out.

Then there's the fact Sanders was on unemployment until his mid-30s, and that he stole electricity from a neighbor after failing to pay his bills, and that he co-sponsored a bill to ship Vermont's nuclear waste to a poor Hispanic community in Texas, where it could be dumped. You can just see the words “environmental racist” on Republican billboards. And if you can't, I already did. They were in the Republican opposition research book as a proposal on how to frame the nuclear waste issue. Eichenwald's list goes on. True, the GOP’s portrait of Sanders strips him of the grace notes which make life tolerable—context, nuance, the chance of personal growth, the wisdom that time brings. It fails to acknowledge that he emerged from a marginal early adulthood to become a capable small-city mayor. But, as JFK often said, life is unfair—and, as Sanders' own followers often exemplify, politics in the age of social media is soul-shriveling and feral.

Eichenwald's point is simple: from Clinton, Sanders enjoyed a privileged immunity. What Trump would dispense is Hobbesian savagery.

It’s little wonder that mainstream Democrats are petrified at the prospect of nominating Sanders: quite reasonably, they believe he will lose to Trump and take the party—to which he does not even belong—down with him.

They find his supporters fanatical and intolerant of difference, a wrecking crew in waiting. They fear his penchant for ideological litmus tests which are demonstrably unpopular. They cringe at his embrace of left-wing authoritarians in Latin America. They worry that the GOP would bury him in a tsunami of sludge—some of it exaggerated, some not. They believe that he would doom the more moderate House members in swing districts whom Democrats need to retain their majority, and eliminate their long-shot hope of retaking the Senate. They remember that in 2016 Sanders lost the primaries to Clinton, no paragon of popularity, by 3.7 million votes.

But Sanders has further marginalized himself electorally by helping divide the party's left. And in doing so, he has lowered his own ceiling, a misstep he could ill afford.

His hitherto friendly rival, Elizabeth Warren, hoped to consolidate progressives and reach out to moderates with a broad-based appeal. In response, Sanders resorted to self-righteous political narrowcasting rooted in doctrinal rigidity and and demographic divisiveness—forcing Warren to the ideological frontiers in her attempt to win over ardent progressives.

First, he chided her for deviating from his ferocious embrace of single-payer, however unpopular it is among voters as a whole. Second, his campaign cast her as the candidate of "highly-educated, more affluent people," as if those votes are less desirable than those of Sanders-style class warriors. As electoral politics, this calculated myopia breeds an inflexibility which kills coalitions and exacerbates disunity. But as a short-term tactic, it weakened Warren on the left and prevented her from becoming a more inclusive candidate. Sanders has ever had a taste for Pyrrhic purism.

From there, the conflict became even less edifying. Sanders' online supporters inundated Warren with ridicule; Warren claimed that Sanders told her that a woman could not win the presidency. When he denied this charge on the debate stage, Warren declined to shake his hand after the event concluded - following which, intemperate Sanders devotees assailed her with snake emojis. Sanders' people accused Warren of mischaracterizing a private conversation; hers accused Sanders with misogyny. The hope that either could unify the party abruptly evanesced.

In light of all this fractiousness, the case that Sanders and company make for his unique electability in November is political helium. Self-mesmerized by fantasy, they imagine repealing the laws of electoral gravity by energizing three otherwise disengaged groups into a decisive bloc: Voters who switched from Obama to Trump; Obama supporters who stayed home in 2016; and citizens who rarely, or never, vote at all.

Conjuring this newly-aroused coalition of the politically cataleptic requires magical thinking of the most tendentious kind. By what alchemy does Sanders transform these previously passive souls into zealous cognoscenti of democratic socialism? Single-payer healthcare? Free college?

Perhaps this could work with some cohort of young people. Otherwise, one suppresses a smile envisioning this coalition of the comatose swamping Trump in a sudden tidal wave of low information voters. If anyone can bestir low-information voters, it's that personification of low information, Donald Trump.

In Vanity Fair, Peter Hamby deconstructs the real-world difficulties of beating Trump by building a movement of lightly-informed, intermittent voters based on policy proposals and political ideology. Writes Hamby:

There are plenty of divisions in our conventional wisdom—insider versus outsider, progressive versus moderate, young versus old—but one of the biggest splits in American politics is simply between those who follow politics closely and those who do not.

It's a split that maps, if not perfectly, onto the gap which emerged between college and non-college-educated voters in 2016. The latter set are often low-information voters who view politicians and media with contempt, deciding to sit elections out. Trump has exploited them to powerful effect. This president has made politics about culture—not just policy. He found a way to attract new voters, particularly rural and non-college-educated whites who previously thumbed their nose at conventional politics. Because he's a pure attention merchant, he doesn't care what screen he appears on, as long as he is there. Because he lacks an ounce of shame, it all works, with or without the blessing of the legacy press . . .

Not since Barack Obama have Democrats had a figure compelling enough to overwhelm the information divides in our culture, to appear on all screens at all times and capture the attention of people who don't usually follow politics: black people, Hispanics, young people, low-income voters, and people who just think politics sucks. Obama, one recalls, was a uniquely eloquent and charismatic figure who, because he aspired to be America's first black president, became a phenomenon who transcended ideology. That's not Bernie Sanders—who, like Joe Biden, is another septuagenarian white guy.

On this subject, Hamby relates the experience of former Obama lieutenant Jon Favreau, who recently emerged from conducting focus groups worried about "off-and-on-Democrats who don't follow the news closely." Awash in cynicism and distrust, these folks expressed indifference to Biden and Sanders and—inimical to Sanders' theory of the case—a disdain for government itself. Reported Favreau: "No one could remember the last thing the government had actually done to improve their lives, except one woman in Miami who brought up the Affordable Care Act."

Hamby's inescapable conclusion is that Trump enjoys a huge advantage over Democrats among low-information voters. Similarly, Politico quotes a former senior member of the Obama campaign team who challenges Sanders' fundamental thesis:

My concern about Sanders would be just how low his ceiling may be. The argument Sanders would make is that he can turn out tough-to-turn-out voters. While many are progressive like the Sanders base, most aren't, most aren't connected to politics, they tend to be more moderate. I think it's a falsehood that all people not registering to turn out are looking for the most classically liberal candidates—that's just not true.

The path forward seems clear. The best chance for Democrats to win is by working with the electorate they have, not the latent would-be electorate Sanders imagines they might—maybe, possibly—conjure at some point in the future.

His candidacy rests on a dangerous dual delusion: that he can upend our electoral dynamics by imbuing passive Americans with an ideological fervor never seen before; and then spark a political revolution in which mass support for democratic socialism compels our otherwise polarized Congress to enact it.

Yet Bernie's acolytes see him as an all-purpose Pied Piper galvanizing a previously slumbering left-wing America into a permanent majority of political obsessives who, once awakened, will be just like . . . well, them. There is something oddly touching about this fever dream—and much that is awash in solipsism and bathos.

Here is Nathan Robinson in Current Affairs: "The democratic socialist vision is one that is worth fighting for. People who hear about it, understand it, and see it in action feel like they have been touched by something special. Why do you think Bernie supporters are passionate like no other candidates are? Why do you think they cried so much when he lost in 2016?"

Beats me. But Robinson thinks he knows: "It's because they had come to believe that old leftist slogan, A Better World Is Possible, and seeing that better world snuffed out before their eyes was crushing. We are for Bernie not because we love Bernie, but because we love humanity and have confidence in what it could be."

Just a thought: Any clear-eyed lover of humanity might focus first on the existential urgency of defeating a racist, xenophobic, and unstable president with no regard for norms, truth, the rule of law, the Constitution, other people, or the earth we inhabit.

So now, reality. Jim Messina managed Obama's reelection campaign in 2012. For several reasons, Messina told me, Bernie Sanders is the general election opponent Trump and his advisors most desire. His analysis goes like this:

Absent some unexpected cataclysm, the contested Electoral College map in 2020 will be the smallest in modern political history: Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Michigan, and, more difficult for Democrats, North Carolina and Florida. In all likelihood, the only state Democrats carried in 2016 which will be in play is Minnesota.

This mini-map of closely-contested battleground states, Messina emphasizes, requires success in two indispensable areas.

First, Democrats must reach swing voters—including suburbanites, blue-collar workers, rural Americans, Republicans disenchanted with Trump, and the independent-minded women who were so critical to flipping the House in 2018:

Here, Messina notes, Sanders virtually ignores the importance of pursuing these crucial groups on anything close to their own terms. Moreover, his strident rhetoric and uncompromising proposals are likely to repel more people than they attract.

After an extensive study of Obama/Trump voters in three critical Midwestern states that Trump carried in 2016— people who are one of the lynchpins of Sanders' argument for his electability—Messina found little evidence that they are waiting for Bernie. As they feel their lives getting harder, they focus on core issues like healthcare and the burden of working two jobs. But if one mentions socialism they swiftly shut down. Right or wrong, they're worried about bigger government and higher taxes—which, they believe, would make their lives harder still.

This bodes ill for selling the Sanders agenda. He lacks legislative achievements to cite as evidence that democratic socialism delivers results. It is easier for Democrats to advocate expanding Obamacare than to defend Medicare for all. Blue-collar Americans want practical help with their lives, Messina believes, not what they perceive as elaborate government schemes which are unlikely to pass—and which are anathema, as well, to many independents, suburbanites, and erstwhile Republicans whose modest hope is for sane and functional governance which lowers our political temperature.

In sum, Messina concludes that Sanders would put Democrats on the defensive among critical voters, stuck explaining why democratic socialism is the answer to their all-too-real problems, or the antidote to our crippling political dysfunction.

If you're spending too much time explaining, you're losing.

Second, Democrats will need to expand their electorate by increasing turnout.

Here, Messina believes that the Sanders approach is grounded in quicksand. Like other professionals, he doubts that Sanders can create a dispositive mass of occasional and non-voters in battleground states inspired by an ideological argument for democratic socialism—which polling already suggests would be likely to alienate politically-engaged swing voters who are far more likely to cast a ballot.

Nor is Sanders the only one who can arouse young people; they will respond to a credible candidate with a persuasive agenda on issues like climate change, gun violence, and affordable college. Then there’s this: Donald Trump is the greatest energizer of Democratic turnout since Hoover.

In 2018, both parties turned out the largest midterm vote in over a century. That was all about Trump. In 2020 Trump will stimulate Democratic turnout more than any Democrats can on their own. Unless, of course, the Democrats nominate a candidate who alienates more critical voters than he drives to the polls.

Indeed, former Pennsylvania governor Ed Rendell is among the many experienced professionals who see Sanders as a net electoral depressant: "Is Bernie right that his candidacy will produce more votes because there are some Sanders voters who won't vote for anyone else? Yes, he is. But that number is dwarfed by people who won't vote for Bernie based on his positions.”

The unique intensity of Sanders' supporters, Rendell adds dryly, does not translate to the breadth of appeal Democrats need to beat Trump. "If I go in and cast an enthusiastic vote for my candidate," he asks, "how many votes does it count as?"

Finally, Messina concludes, the Democratic candidate must suit the political zeitgeist after four years of Trump. In the modern era, our presidents have tended to embody a reaction to the previous president: Bill Clinton after George H.W. Bush; George W. Bush after Clinton, Obama after Bush —and, especially, the self-proclaimed quasi-populist superman, Donald Trump, after the cerebral, technocratic Barack Obama.

Trump has left us weary and fretful, a nation of people ceaselessly on edge. Sanders' "political revolution"—his heated language, sweeping proposals, and pledges of relentless confrontation in pursuit of his societal utopia, however heartfelt, are wrong for such a febrile moment. In 2020, Messina believes, Democrats need an antidote to Trump's shrillness, divisiveness, disloyalty, cruelty, vulgarity, volatility, and lawlessness. Most of all, they need a permanent escape from Trump’s inexhaustible, exhausting, and deeply destabilizing need for our attention.

All of which argues for a calm and collected unifier who promises his or her best efforts to transcend divisions, seek consensus, and tackle our most pressing issues—like healthcare, climate change, an infrastructure overhaul which creates jobs in the present, and retraining workers for the jobs of the future—in a practical way that people can actually believe will make their lives better. In shorthand, a candidate who can win.

Success in 2020 is not about waging an ideological crusade for which support is deep but narrow. It is about the gritty and pragmatic work of squeezing out an Electoral College victory in three or four states by appealing to the temper of those most likely to vote.

This may seem prosaic. But, for Democrats and for America, the difference between winning and losing is close to existential—the hope of healing our deepest wounds and reclaiming our collective decency.

For now, in our extremity, the task of winning is revolution enough. It cannot be entrusted to a man too blinded by his own imperatives to deliver us from Trump.