A Defense of Art for Art’s Sake

Concerns over “relevance,” argues Jed Perl, obscure the reality of art’s eternal role in the cultivation of the individual spirit.

Authority and Freedom A Defense of the Arts by Jed Perl Knopf, 176 pp., $20

In politically tumultuous seasons, an old argument over whether art needs to be justified according to political or social standards returns to the pages of national newspapers and magazines. Can the arts matter if they don’t take up the central moral and political challenges of the times?

In this slim but powerful volume, critic Jed Perl, a longtime writer for the New Republic before that magazine’s implosion, provides a moving and passionate defense of the arts in and for themselves. He notes that the question of the intrinsic value of art is one he never expected to need to address. For him, it is a given. For others, it has become a questionable hypothesis.

The book’s six thematically connected chapters can stand alone as individual essays, and they blend Perl’s deep cultural expertise with autobiographical stories that illustrate the power of art to fundamentally change a person’s life. As a professional cellist, I approached the book with great interest, but also some anxiety: Wondering about the future of Beethoven and Schoenberg in a TikTok- and Twitter-dominated world keeps me awake at night. Perl’s book offers reassurance that great art has a justification and a future regardless of the apps people use to access it—and regardless of social media’s ability to shorten and damage our attention spans. The two words of the book’s title are poles that Perl’s arguments move between. A core question that comes up repeatedly—“what’s the point?”—speaks to the first pole, of authority. What’s the point of a Vermeer painting or a Mozart piano concerto if it doesn’t concretely improve society? The assumption underwriting this kind of question is that the work of art does not exist on its own authority, and so needs to borrow it from elsewhere. Perl writes,

The idea of a work of art as an imaginative achievement to which the audience freely responds is now too often replaced by the assumption that a work of art should promote a particular idea or ideology or perform some sort of civic or community service. Instead of art-as-art, we have art as a comrade-in-arms to some supposedly more stable or socially significant aspect of the world. Now art is all too often hyphenated. We have art-and-society, art-and-money, art-and-education, art-and-tourism, art-and-politics, art-and-protest, art-and-fun. Race, gender, and sexual orientation become decisive factors, often as a way of giving some readily comprehensible coordinates to the inherently uncategorizable nature of the artistic imagination.

What does Perl set opposite these attempts to borrow authority to justify art? The freedom of the artistic imagination, which invites audiences, readers, and listeners into its domain through the experience of the artwork. I frequently interact with people inside the art world—in music, theater, dance, and museums—who are beset with worry over how their work might be made more “relevant”—which is to say, how it might be made to bring about societal change. But I have never met, in any part of the world, a person of any economic class, racial background, age, gender, or religion who was not moved upon hearing a live performance of a Beethoven symphony.

Recently, I performed the seminal Bach Suites for solo cello in the lovely city of Antigua, Guatemala. I know some people at my concerts have never heard Bach before—and yet they are transfixed and deeply moved. Where is the “relevance” in this scenario? The answer lies in the music itself and nowhere else.

Perl takes on relevance in a similar way:

I want us to release art from the stranglehold of relevance—from the insistence that works of art, whether classical or contemporary, are validated (or invalidated) by the extent to which they line up with (or fail to line up with) our current social and political concerns. I want to convince a public inclined to look first for relevance that art’s relevance has everything to do with what many regard as its irrelevance.

Perl’s primary expertise is in the world of visual art, and some of his most fascinating explorations of the freedom of the artist begin in the studios of great painters. The studio—as well as the stage, the study, and the workshop—is a sacred space. What happens there is a subject he takes up in a chapter titled, “The Idea of Vocation.”

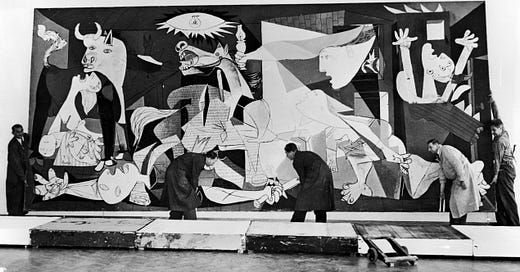

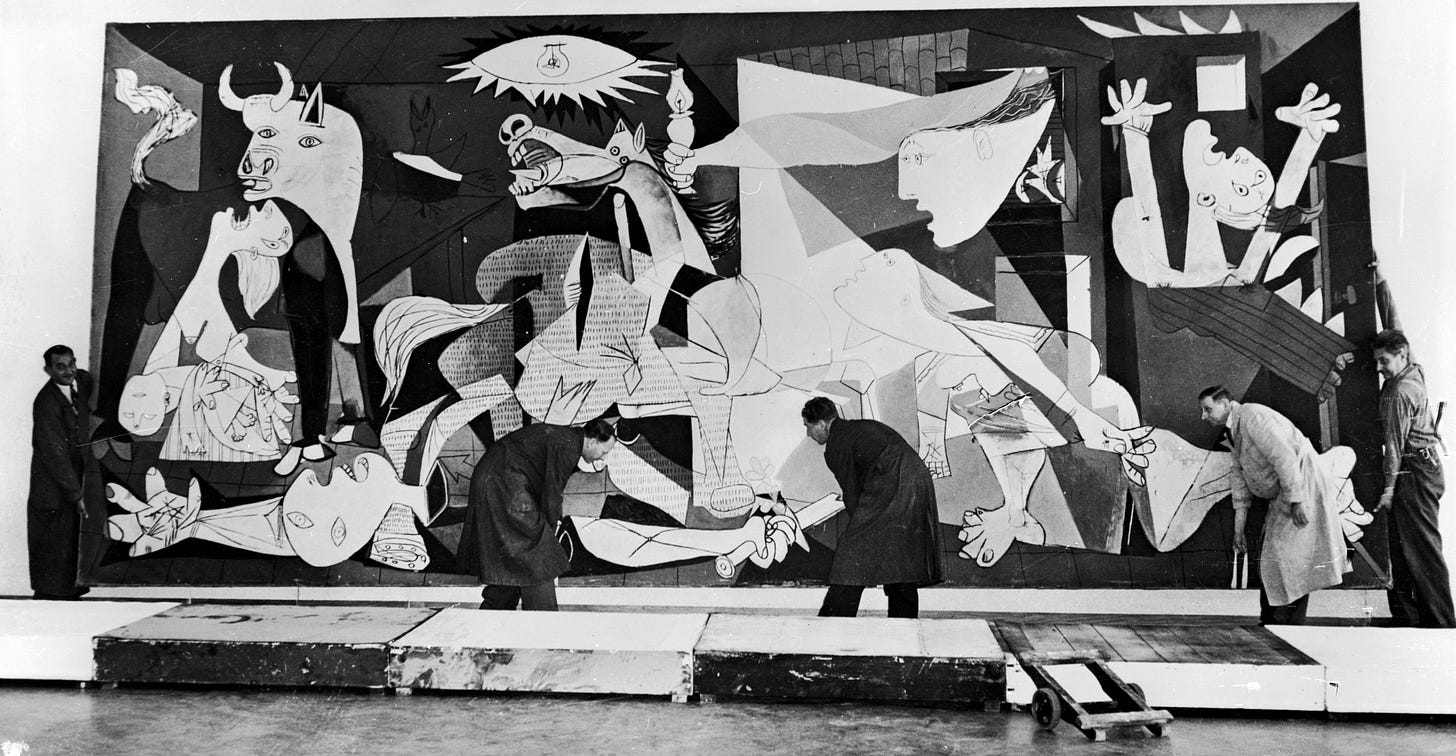

What does a painter do as he stands in front of a blank easel? What goes through the mind of a great tenor before going onstage to sing La Bohème? The half-dozen pages Perl spends on Picasso’s masterpiece Guernica give these questions a powerful and illuminating treatment. Perl takes us on a journey into Picasso’s psychological and emotional background as he outlines the complex history of the iconic painting. Far from simply emerging in a mechanical way as a response to the brutality of Picasso’s time, Guernica was created to bear the heavy themes of Picasso’s inner life. Perl describes the painting as “a meditation on human chaos, confusion, and agony that drew together themes that had long preoccupied Picasso.”

Perl employs the tone of the learned professor, but one whose fascination and curiosity have survived and even grown stronger through the decades. The experience of reading these essays is akin to taking a course in art. Perl frequently quotes great creators and artists, giving his book a feeling of grand and inviting context, like a friendly conversation at a dinner party. For instance, regarding the nature of vocation, I was particularly struck by Katherine Anne Porter’s observations about Virginia Woolf: “She wasn’t even a heretic, she simply lived outside of dogmatic belief. She lived in the naturalness of her vocation. The world of the arts was her native territory; she lived freely under her own sky speaking her mother tongue fearlessly. She was at home in that place as much as anyone ever was.”

Perl’s explorations of the complex relationship and inherent tension between authority and freedom also lead him down surprising paths. In a chapter that begins with an epigraph from André Malraux—“All art begins as a struggle against chaos”—Perl brings us into the wonderful world of fabric weaving via the German-Jewish Bauhaus-trained artist Anni Albers. In the 1950s and 1960s, taking cues from the weavers of ancient Peru, Albers created what she called “pictorial weavings.” Perl believes her treatise On Weaving to contain the clearest articulation of the way authority and freedom can work in tandem: “Great freedom can be a hindrance because of the bewildering choices it leaves to us, while limitations, when approached open-mindedly, can spur the imagination to make the best use of them and possibly even to overcome them.”

This brought to mind a reflection on the possibility of true improvisation from cellist János Starker, with whom I was fortunate to have studied: “It’s very seldom that anybody truly improvises, where he or she has never tried something before. Instead, improvisation is a selection process. You have four or five different ways of doing certain things, and you pick one because of the circumstances of the performance or how you feel in the moment.”

A great weaver and a great cellist speaking about their art: Perl’s hosted conversation even spills out beyond the pages of his book.

Authority and Freedom’s argument for the intrinsic value of art leaves readers with questions to ponder. This may be the result of both Perl’s inviting and creative combinations of memoir and learned analysis, which naturally elicit personal reflection, and arguments possibly left unfinished. Part of me wishes he had brought more strength, energy, and specificity to his case against those who would instrumentalize art and trivialize the individual’s experience of it. It is unclear how many people will find Perl’s argument convincing who weren’t already supportively listening from his section of the courtroom.

As for me, while I’m sleeping better, I also continue to reflect on the concern for relevance. How could “relevance” explain my love for Dante, which began in high school and was made permanent and invincible under the great Robert Hollander at Dartmouth? I don’t think the concept is ultimately useful for understanding a 17-year-old American Jew’s enthusiasm for a thirteenth-century Florentine Catholic poet. Taking it one step further: “relevance” is not the right tool for reaching the mysterious core of the relationship between any individual and the art that moves them. That’s what Jed Perl knows so well: that the only way to reach that core is to follow the music.

Speaking of, I think it’s time for some Schoenberg.