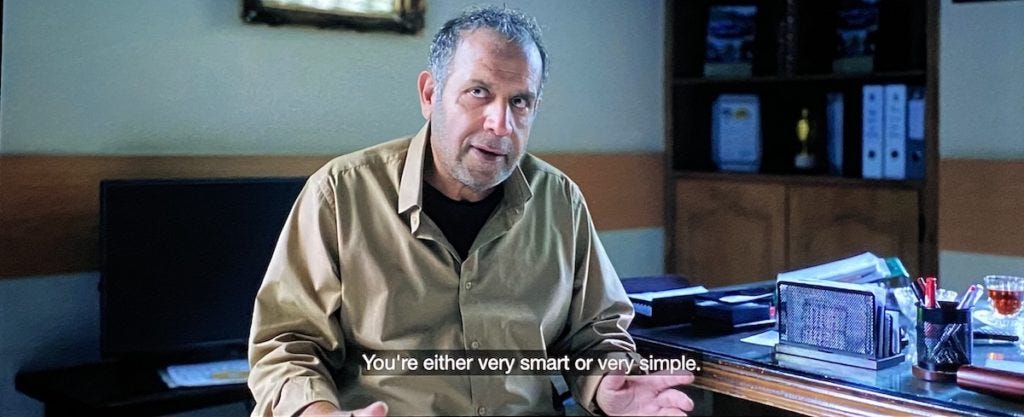

About three-quarters of the way through A Hero, one character says to our protagonist, Rahim (Amir Jadidi), “You’re either very smart or very simple.” The implication here is that Rahim—a prisoner who has become a cause célèbre after attempting to return a bag full of gold coins to its owner despite being on a weekend furlough from prison, where’s he’s serving a sentence for being unable to pay a debt—is either gaming the system or a dullard waltzing through life.

In truth, Rahim is probably just an average guy muddling along. But the pleasure of Iranian auteur Asghar Farhadi’s film is that it allows us to make up our own mind, and not only about Rahim. A Hero does not insist we like or dislike any of the characters. They’re all acting reasonably and rationally; realistically, though not always honestly.

A Hero has at its heart a lie, and the broader lesson here is that in the age of social media, of phones that keep track of every communication, of the omnipresent risk of virality, there are few lies that can remain intact for long if someone is committed to uncovering the truth. The film opens with Rahim exiting prison for his furlough and heading to the tomb of Xerxes to meet his brother-in-law, Hossein (Alireza Jahandideh), in an effort to partially pay off his creditor and receive permission to leave the prison.

Rahim has in his possession 17 gold coins, which will pay off about half of his debt. After his creditor, Bahram (Mohsen Tanabandeh), refuses the half-payment without Hossein backing the rest of Rahim’s debt—a favor Hossein is nervous to do, given Rahim’s lack of employment—Rahim decides to find the rightful owner of the gold coins. They weren’t his, you see, but a stranger’s left in a bag he found near a bus stop.

Except, that’s not true. It’s not true that Rahim found the bag; a woman he hopes to marry found the bag. But he cannot tell anyone about her because of Iran’s rulers’ medieval understanding of relationships between men and women. So, when the bag is returned and the woman who takes it dissolves into the desert dust, Rahim has difficulty explaining where the coins came from or where they went. Whether they existed at all, in fact.

Theories arise to fill in the gaps. Bahram believes Rahim made up the whole story to retrieve his honor. Social media gadflies suggest the prison invented the scheme as a way to deflect attention from horrible conditions within the prison itself. Text messages reveal Rahim’s timeline of events to be false. A ruse involving Rahim’s lady-friend casts doubt on his honesty. A video of Rahim attacking Bahram for his insults further damages his credibility. Rahim’s own retelling of the effort to turn the gold into currency doesn’t square with what we, the viewer, saw. The lies compound and compound until he’s hopelessly trapped within their web.

A Hero reminded me a bit of Parasite in the sense that both are, on some level, about liars and the debts they incur. Which in turn prompted me to interrogate my own knowledge of Rahim. Do we know for a fact that his debt was incurred because his business partner absconded with their seed money? Do we even know for sure how his lover procured that bag? All we really know about Rahim is that he’s willing to bend the truth to make himself look good in an effort to get out of prison.

Indeed, the most sympathetic character in the whole film is Bahram, who was forced to liquidate his savings and sell off his daughter’s dowry, destroying her prospects of marriage, to pay off the loan shark Rahim had taken money from. Bahram only did this because his sister was (is?) married to Rahim, and her complete absence from the film—despite the fact that their son, Siavash (Saleh Karimaei), has difficulty speaking and clearly needs the aid of a stable family—makes us wonder just what Rahim was like prior to his imprisonment.

Bahram’s frustration with Rahim’s newfound celebrity and the suggestion that he should have his past sins forgiven because he did the bare minimum to be a decent person is the most sympathetic emotion depicted in the film. And Farhadi deserves a great deal of credit for refusing to turn Bahram into a sneering villain; we might think poorly of him at first, but Bahram’s the first to see through Rahim’s charade.

For all the shifting perspectives and all the different narratives deployed by Rahim and his backers, for all the confusion caused by conspiracy theorists on social media, Farhadi has, interestingly, made a film about the absolutely concrete nature of truth. Truth is not slippery; truth is hard and fast. And Rahim’s decision to elide the truth to help himself and his lover and his family is, finally, the cause of many of his problems.