A Nation of Promise

Tracing a man through history, from enslaved child to American citizen to great-great-grandfather.

[Editor’s Note: This essay is adapted from Ted Johnson's book When the Stars Begin to Fall: Overcoming Racism and Renewing the Promise of America, which is now out in paperback. Order a copy today. It’s phenomenal. —JVL]

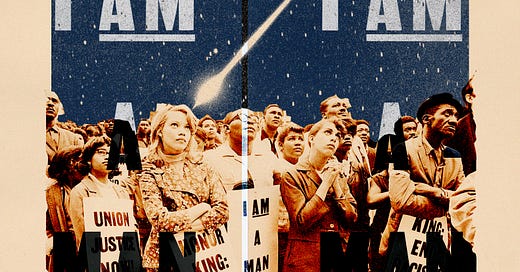

There are few things Americans want to be true more than the vision outlined by a young black preacher in 1963 at the foot of the Lincoln Memorial. With a melodic cadence etching divinely inspired prose into the nation’s conscience, he told us of his dream for a country that judges people based on the content of their character and not by the color of their skin.

Today, most Americans want his dream to be true because it aligns with the nation’s founding principles, which assert that we are all created equal with rights to life, liberty, and opportunity. We want to realize his vision because it would mean that we have finally managed to put the nation’s less-than-admirable record on race behind us. We want his words to become reality so that we no longer have to talk about racism and its effects on the United States and the Promise. If only we could skip forward to King’s dream, our democracy would be more complete—it would finally become closer to the vision of what it means to be truly American.

Yet while we want the dream badly, we do not agree on exactly what it is. Some of us believe the dream depicts a colorblind meritocratic society full of citizens who no longer see race. Others of us think it describes a nation where racial diversity is embraced as an invaluable feature of American culture without being determinative of our American experience.

And we do not see eye-to-eye on the exact problem that this vision for America is supposed to resolve: Does it remove racism as an overused excuse employed by people dissatisfied with the nation, or does it now free up the efforts and ingenuity of the many who have been bridled by its presence? That is, some want the dreamed America because it means racism can no longer be used as a crutch, while others will be glad that it can no longer be used as a cudgel. Those many who agree that racism divides us cannot seem to find common ground on what it is, what it does, how it is used, or even, somewhat surprisingly, who is harmed by it most.

Such disparate perceptions of what racism is and who is truly harmed help explain why racial tensions and conflicts are felt most deeply when they become public and emblazon our television screens, newspapers, and social media. There, we see black women scaling the Statute of Liberty in New York City and snatching down the Confederate battle flag in South Carolina. We watch as white women from Oakland, California, to Washington, D.C., make national news summoning law enforcement to minor interracial conflicts in public parks and coffee shops. We watch as shirtless black men confront heavily armored police officers in the dark of night, lit only by helicopter spotlights and burning cars. We observe white men with torches marching in ranks across university campuses screaming, “White lives matter!” and “You will not replace us!”—flames illuminating their faces as they hold a candlelight vigil for the nostalgic conception of the country of their fathers and grandfathers.

Instead of attempting to understand each other better, we quickly choose to take sides based on who we believe was wronged and who was justified in their actions or responses. And then, just as quickly, we move on. These incidents are viewed as unfortunate flare-ups of race relations instead of as symptomatic of some deeper, enduring national problem with racism that should command our attention after the latest fire has been extinguished. But a few strong political winds fan the flames of some other issue that grabs our attention, and the nation leaves the glowing embers of racial discord unattended, only to feign surprise that it remains an issue the next time we find ourselves ablaze.

A nameless entry on a U.S. census form epitomizes the current choice before Americans and the United States. Though the narrative arc of the presidential name my paternal great-grandparents gifted to the family—Theodore Roosevelt Johnson—seems quintessentially American, it is the missing name in my maternal lineage that is more apt.

Hoping to learn more about the cast of ancestral characters that my grandmother often recalled, I turned to the National Archives. This institution enshrines the sacred texts of our civil religion—the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the original Bill of Rights—and houses decades of census records.

Before the Civil War, enslaved black Americans were recorded on census forms only by age and sex—no names. Guided by my grandmother’s oral history, I found the nondescript listing of an eight-year-old black boy in the 1850 U.S. Census Slave Schedule. He was owned by the Fain family, which lived in the same patch of southwest Georgia where I spent childhood summers on my grandparents’ farm avoiding fire ants, chasing fireflies, and going to church with strong-willed folk on fire for the Lord.

Over three censuses, I traced his evolution from an unnamed enslaved child into an American citizen with the right to vote. By 1870, the United States recognized him as William “Bill” Humphrey, my great-great-grandfather, who appears in the census free of the Fain name. Instead, Bill unilaterally renamed himself to demonstrate kinship to his now-freed siblings—scattered from the lower left corner of Georgia to north-central Florida—who adopted the name Humphrey.

Similarly, the earliest citizens of the United States unilaterally decided to rename themselves. By the time of the nation’s founding, the word America had come to mean the New World, and residents of the colonies were often referred to as British Americans or English Americans. Our country announced itself to the world in the Declaration of Independence, opening with, “The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America.”

Since our inception, we have chosen to be called Americans, and the world today refers to citizens of the United States and the nation itself as such. In choosing this name, the nation-state’s first generation of leaders associated themselves with their vision of the possibilities the New World represented—the right to “institute new Government” and provide “new Guards for their future security” so that a country could be born that recognizes human equality and the attendant inalienable rights. America became the name of a nation of Promise.

And just what is the Promise? It is that all men and women are inherently equal, that each of us will respect and defend the rights and liberty of others, and that the state will not deny or unjustly hamper our equality or our exercise of liberty. The Promise is not the American Dream. The Dream is a question of opportunity and economic attainment. The Promise, however, is about a person’s basic value and the state’s fundamental obligation to protect one’s rights.

But promises cannot administer governance; only people within systems can. The United States became that governing entity, one that has often fallen short of the Promise imbued in the America that trails its title. The United States of America may be the official name of our country, but the United States and America are not synonymous. The geopolitical nation-state known as the United States is not the Promise; it is governed by its interests, even when they are antithetical to the Promise, as history has shown. In this regard, it is important that we have chosen American for ourselves and not United Statesmen.

The natural inclination of nation-states is to do what is in their best interests, but the natural tendency of people who call themselves Americans must be to do what is right and just in accordance with their professed ideals. For all the nation’s shortcomings over the course of its relatively short life, the tremendous progress it has realized is the result of Americans insisting it be more perfect. The work of real Americans is to compel the United States to ensure security and prosperity, not as ends unto themselves, but solely as a means to permit equality and liberty to exist unmolested.

The moniker American is not the exclusive terrain of the overzealous who drape themselves in the national flag and lather their words with clichés ripped from the civil religious canon, often investing themselves in the items of Americana more than in the principles of America and the people who constitute it. Rather, the purest form of America is found in the evolving lot who have helped the United States endure and occupy the mantle as the oldest constitutional democracy by fighting for incremental progress over the generations. We Americans are imperfect, succumbing at times to passions and self-interest, as fallible humans are wont to do, but our aim is straight: making the Promise more real and more accessible.

Whether we meet the challenge or not, we will inscribe our mark for posterity and for the annals of history. When the stars begin to fall, we get to decide if they are falling out of the sky as the Promise collapses on itself, or if they are finally falling into place behind the brightness of a new day and the unmistakable declaration that America will be.