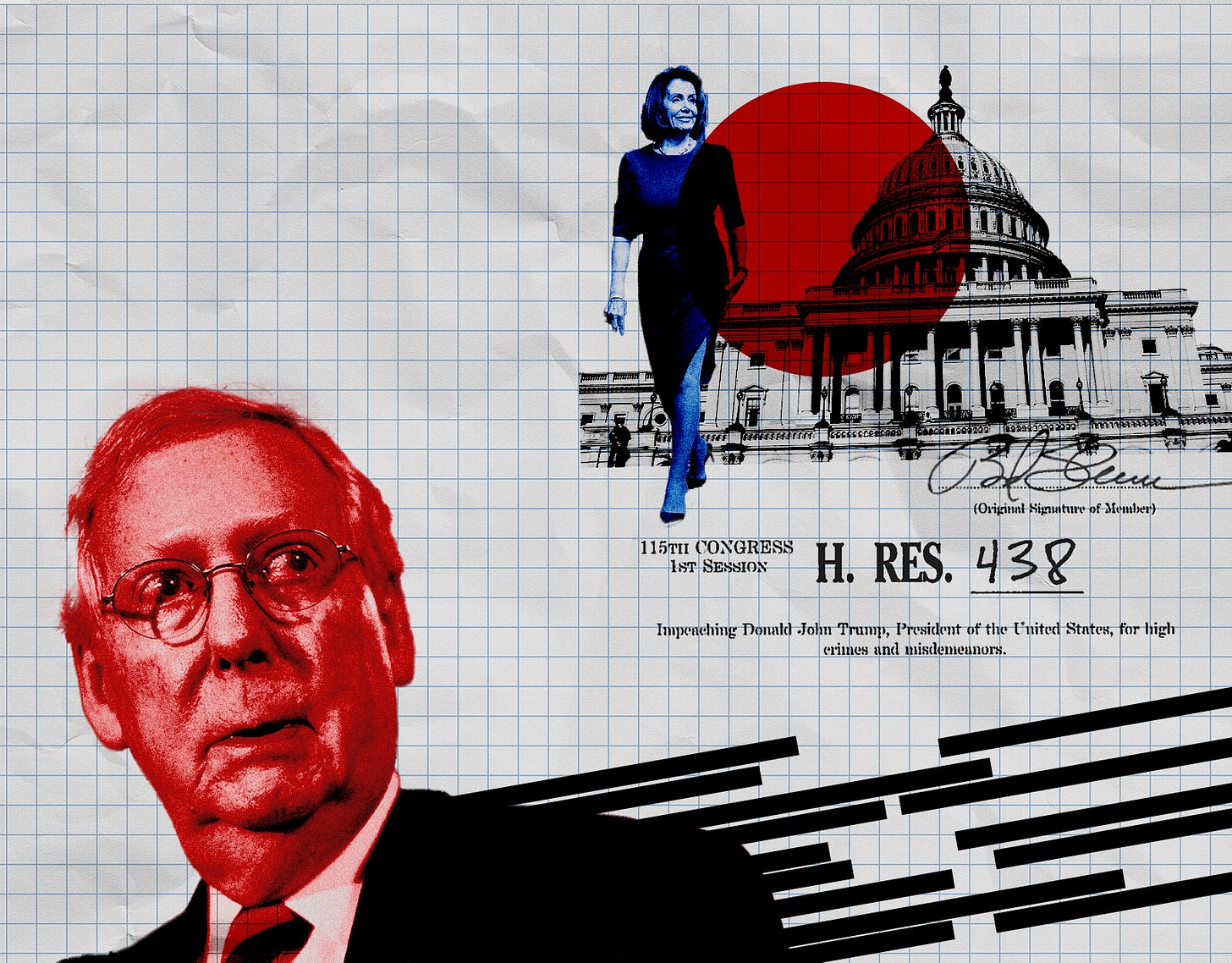

America's Mitch McConnell Problem

The Senate majority leader is a danger to the Constitution.

The United States has a problem. The Constitution of the United States has a problem. The Senate of the United States has a problem.

His name is Mitch McConnell.

He’s the Republican senator from Kentucky and the Senate majority leader, and he’s fundamentally distorting our constitutional norms and damaging the health of American politics today.

The president has been impeached by the House of Representatives and one man stands in the way of a fair trial in the Senate: McConnell.

He has promised that there would not be a fair trial on the pattern of previous impeachment trials in the Senate, with rules negotiated by the two parties that allow for both sides to call witnesses and makes their cases.

He has laid down a diktat that the matter will be dispatched with as quickly as possible, without any witnesses or new documents.

He has repeatedly promised to violate the new oath he will take to do impartial justice—as has his Judiciary Committee chair, Lindsay Graham.

He has publicly claimed that the case is worthless before allowing the case to be made.

He has disparaged the sole power of impeachment of the other house of the Congress.

He has insisted that his caucus stay in lock step with him as if impeachment were a matter of ordinary politics, rather than an upcoming trial where all of his colleagues are equal judges of the House articles.

In sum, McConnell’s actions to date prevent the Senate from organizing the trial--whatever the ultimate verdict--in a way consistent with the constitutional design and with a sense of fairness in the body politic.

Consider, by contrast, the speaker of the House, Nancy Pelosi.

Like many people on her side of the debate regarding the impeachment of President Trump, we did not agree with all of her decisions along the way.

We thought, for example, that she took too long to move to impeach a president who has been abusing his powers in multiple ways that extend well beyond the two passed articles.

But we did not have the responsibility that she had for organizing a fair and difficult process under the unprecedented condition that the president would continue to abuse his power against every step of the inquiry, and that he would be aided by a compliant House minority, a faithless Senate Majority Leader and a fearful Senate majority.

Knowing that conviction in the Senate for any charge would be difficult, Pelosi was well aware of the electoral risks for her caucus and, much more important, a risk for the polity that her missteps might enhance the reelection prospects of a president who abuses his power.

In these circumstances, her commitment to the Constitution and her accomplishment in leading the House to well-crafted impeachment articles was remarkable and historic.

As the Federalist Papers explain, the Constitution was designed to induce ordinary politicians to translate their ambitions and their partisan positions into viable constitutional arguments—whether or not they were sincerely motivated by a constitutional understanding to begin with. As long as politicians felt constrained to show their constituents—and the public more generally—that they were living up to their oaths by responding to the arguments of partisans on the other side and making their own perhaps politically-motivated, but constitutionally-elevated arguments, this new vision of a constitutional republic could succeed.

One could see this dynamic at work at the outset of this impeachment inquiry. Speaker Pelosi announced an inquiry on her own authority, without a vote of the whole House.

In the past impeachments there were such votes, with resolutions tailored to the subpoena needs of the specific inquiries. But since the time of the Clinton impeachment the rules of the House regarding the power of committee chairs had changed and Pelosi believed that the new rules gave her discretion to launch the inquiry on her own.

She was attacked for this by Senate Republicans and the White House. These attacks were motivated by partisan desires to protect or defend the president, rather than any sincere concern with the Constitution—but the arguments had merit.

Partisan Republican defenders of the president had found a vulnerability in the speaker’s position. The Constitution vests the sole power of impeachment in the House, not in the speaker herself—unless the House formally delegated that power to her, which it had not done.

So Speaker Pelosi heard these criticisms and called for a formal vote of the House, similar to the processes in past impeachment inquiries. Having initially defended her discretion, she listened to her partisan critics and absorbed their arguments. She did not assume that the White House or the Senate majority leader had no right to criticize her procedural decisions.

Instead, she adjusted to the merits of the Republican position and its resonance in the public sphere. She came to understand that the indispensable need for the Congress to have access to relevant documents from the executive branch overrides the president’s privilege claims in impeachment proceedings and so it was important for those proceedings to unquestionably pass constitutional muster.

Pelosi’s pivot made the House Democrats more responsible constitutionalists, more accountable to the public, and they made the case against the president for obstruction even stronger.

In contrast, what has Senator McConnell done in response to the Speaker’s request and the proposal of Minority Leader Schumer that the Senate tailor the Trial Rules for Impeachment to this case in a way that permits the House managers to make their case and the president’s counsel to defend him?

McConnell has shown contempt for the very notion of a fair trial.

Indeed, he and Sen. Lindsay Graham have announced—effectively pledged—that they will not follow the new oath that they will be required to take once the chief justice is invited to preside.

We need to be very clear on this point: Many senators and congressmen throughout American history have not lived up to their oaths, whether it be the regular oath they take upon election, or the special oath for an impeachment trial.

But we can’t think of any previous senator who has publicly promised not to follow their oath. And we certainly can’t think of others who, like McConnell and Graham, previously participated in an impeachment trial in which they purported to be faithful to their oaths and urged others to be as well.

It is not a case that McConnell and Graham are mistaken, or ignorant of their special duty. Rather, they know what they are doing, are conscious that it is wrong, and are willfully pursuing this course anyway in order to support a president whose prospect for anti-constitutional behavior had worried both of them during the 2016 election season. These are why their comments on the upcoming Trial are among the most contemptible by any Senators in American political history.

Fortunately, the ending of this story does not need to be written by Mitch McConnell. A small, bipartisan group of senators can fix this mess in an afternoon.

The main goal should be to enable both the managers for House and the counsel for the president to put on their strongest cases in a fair trial.

The Senate has other duties as well, and the reason for supplementary rules regarding specific impeachment trials in the past has been to balance the need for a full and fair trial with the other business of the Senate. This means there may be restrictions on the number of witnesses called and time allowed to question them. But the point of fair rules is not to constrain the ability of the prosecutors and defense attorneys to put on their best case. It is to make it possible for them to put on a robust case and to balance that need with the rest of the nation’s pressing business.The impeachment of the president of the United States by the House of Representatives is not an act to be trivialized or dismissed. The Constitution demands that the Senate take this action seriously. Senator McConnell is abusing his own office in his attempt to dismiss a trial before it can be conducted fairly.

If a bipartisan group of public-spirited constitutionalists on both sides of the aisle come together, they can tell McConnell that he will only get 51 votes for amending the Rules of the Senate for Impeachment Trials if he works with them to fashion a fair process that allows for crucial documents to be compelled to be produced, and a reasonable number of witnesses to be called—and for reasonable times and procedures be set.

Republicans should be willing to accept the witnesses the Democrats want called, and Democrats should be generous in permitting the president his number of witnesses. By generous, we mean that, contrary to Senator Schumer’s proposal, judgment on the relevance of the president’s witnesses should be made publicly at the trial, with the aid of the chief justice’s rulings, rather than ruled out now.

If the president wants to call Joe Biden, for example, so be it. Objections to particular questions to any of the witnesses, including perhaps the president himself, can be adjudicated at the trial by the chief justice and the senators, acting in their new role as fellow judges.

There is no good reason to fear a fair and complete Senate trial. The House managers will make their case, and whatever additional witnesses they can call in the Senate whose testimony was blocked in the House will be experienced public servants who will, we trust, testify truthfully and appropriately.

The president’s lawyers may be tempted to try to create what some of us would consider a circus, but the character of the president’s defense surely has to be up to him. In any case, the nation will survive a bit of a circus. And ultimately we need to turn to their common sense to judge the president and his defenders.

If conducted under rules acceptable to all Senators, as was the last Trial twenty years ago, at the end of the day, a verdict will be rendered that will vindicate the Constitution and convey to the nation a sense of a fair and orderly process. The only way to get to that outcome is if some Senate Republicans refuse to lower themselves to be the mere agents of an unprincipled and partisan leader and instead rise to the demands of principle and statesmanship.