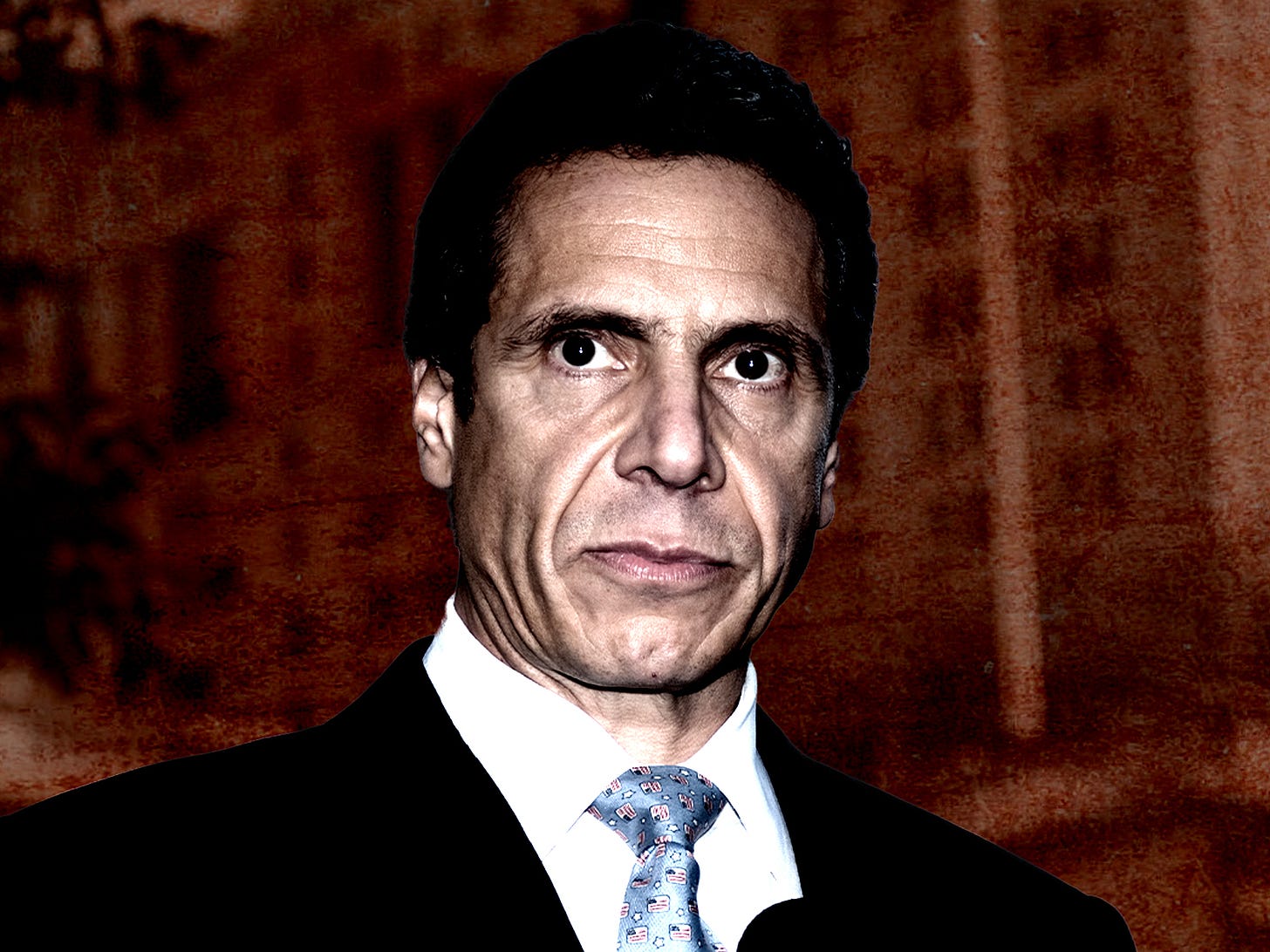

Andrew Cuomo Resigned Because the Democrats Aren't a Cult

Normal political parties can police their own.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo has resigned, thereby demonstrating once again the benefits a political party accrues from not being a cult.

Let’s stipulate to a few things: Cuomo probably did at least some of what he was accused of—and he seems to be admitting as such by saying that he’d “made mistakes.” Also, the Democratic-controlled New York Assembly, which was already part-way through an impeachment process against him, probably made it clear that, unless he resigned, he would be removed.

That made Cuomo’s choice pretty easy: He was guilty and he knew it. So he could fight it out and watch his litany of boorishness rehearsed on the news every night, not just in New York but across the country—and ultimately lose. Or he could resign on his own terms with whatever kernel of dignity he has left.

That choice isn’t dissimilar to the one offered to former Sen. Al Franken, who was driven to resign at the height of the #MeToo movement for far less serious allegations.

For people determined not to give Democrats credit for policing their own side, you could say that it was helpful that in both cases the person succeeding the beleaguered official was also going to be a Democrat. Then-Minnesota Gov. Mark Dayton, a Democrat, appointed Tina Smith to fill out Franken’s term, and New York Lt. Gov. Katie Hochul will take over for Cuomo as governor. So it’s not as if the stakes were astronomically high for the Democrats seeking to oust Cuomo and Franken.

But that also raises an interesting question: When the Republican party had an historically unpopular incumbent president and had the opportunity to impeach him and remove him from office not once—but twice!—why didn’t they do it? It’s not as if removing Trump in 2019 would have made Hillary Clinton president—it would have made Mike Pence president, and this was before he had been unpersoned as a traitor.

The obvious answer is that at the current moment the Democrats are a political party, while the Republicans are a personality cult.

The Democrats have active internal politics, even (perhaps especially) in a Democratic-dominated state. New York Attorney General Letitia James had no reason to fear reprisal—political or otherwise—for investigating the allegations against Cuomo and reporting her findings. The Democrats in the state house probably figured that their prospects as a party would improve without the weight of Cuomo’s alleged misdeeds around their ankles.

No doubt at least some Republicans felt similarly in 2019, even if they didn’t say so. But in the Republican party, criticizing, disappointing, or contradicting the dear leader is an offense worthy of expulsion—if not worse. That’s not to say Republicans don’t have some internal competition, but rather that, to the degree such competition exists, it is between actors competing to show fealty to the Supreme Leader who is himself above and insulated from any such challenge.

There are other explanations, too: The Democrats attract people, especially women, who care about this particular issue. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand is often identified as the driving force behind Franken’s resignation, and she has prioritized issues of sexual harrassment and sexual assault, especially in the military. But that may also be because only the Democrats have room for such people. The Republican party has delighted in elevating serial abusers to prominence, and anyone who made even a peep has been immediately declared persona non grata. The Republican party is a organization where the tolerance of sexual harassment is part of the price of entry.

Whatever else the saga of Andrew Cuomo teaches us, it’s a lesson in how cults corrupt.

Cults are phenomenally good at policing dissent, but that’s about it. Only healthy political movements are capable of policing actual bad actors.