Pull up a chair. We need to talk about black voters.

There is a growing belief that a small, but notable, group of black voters is becoming disenchanted with the Democratic party and that a window is opening for Republicans to begin chipping away at the most stalwart and enduring segment of the Democrats’ electoral coalition.

The genesis of this latest wave of speculation began in the run-up to the 2020 election, when Donald Trump made an explicit play for more support from black voters, especially the men. Initial exit polls suggested it may have worked: Trump seemed to make measurable gains with black voters. And in the months since President Joe Biden’s inauguration, his dwindling approval numbers among black Americans has added additional heft to the idea that a change may be underway.

If you hold all this up to the light at just the right angle, you might be excused for thinking that there may be some minor partisan realignment underway within the black electorate. But—and I cannot say this strongly enough—it ain’t happening.

Before explaining how I can be so sure, let us begin with some numbers. The immediately available exit polls showed Trump increasing his share of the black vote by 50 percent—from 8 percent in 2016 to 12 percent in 2020—and winning nearly 1 in 5 black men. If these splits were right, Trump would have tied for the highest Republican share of the black vote in four decades.

But those numbers were not correct. More reliable, adjusted exit polls—such as one of verified voters from the Pew Research Center and another from AP VoteCast with a far larger sample size—have since been released and tell a different story.

Trump received just 6 percent of the black vote in 2016 and 8 percent in 2020. On average, from 1968 to 2004, Republican presidential nominees earned just over 11 percent of the black vote—which means not only did Trump underperform the party average in consecutive elections, but he also did worse (twice!) than every single Republican nominee since the Voting Rights Act of 1965 except for the two (John McCain in 2008 and Mitt Romney in 2012) who ran against a black guy.

And even then, with Trump facing a not-incredibly-popular Hillary Clinton in 2016, he could only match what Romney could muster against the historic second-term candidacy of Barack Obama. This should not inspire confidence in those Republicans who believe they are at the precipice of tent expansion.

Did the Republican share of the black electorate double between 2008 and 2020 from 4 percent to 8 percent? Yes. And if you had your pay cut at work from $20/hour to $8/hour, and then management doubled your pay to $16/hour, did you get a raise? Sure.

To put a finer point on it: What we are witnessing with black voters today is not an exit from the Democratic party as a result of too much wokeness on the left and the appeal of Trumpism on the right. Rather, we are seeing black Republicans who chose to vote for the first black president (or sat out an election or two so as not to vote against him) return to their voting habits now that Obama is no longer on the ballot. And it seems that a couple percentage points worth of those pre-2008 black Republican voters may have decided to ride it out with Democrats.

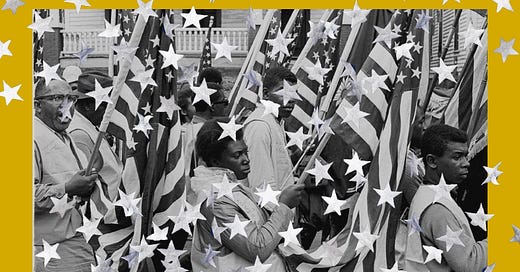

How can I be so sure of all this? Because few things have been as steady in American politics in the last 150 years as black voting behavior. The centrality of federally administered civil rights protections has always governed partisan alignment for the overwhelming majority of the black electorate. It used to be that the Republican party carried this mantle, but since the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, Democrats have made addressing racial inequality a more prominent aspect of its platform. This, more than any other single factor, explains why 9 in 10 black voters have supported Democratic congressional and presidential candidates for decades.

One result of this is what scholars call electoral capture. Defined in a 1998 paper by political scientist Paul Frymer and sociologist John David Skrentny, electoral capture occurs when a group of voters “finds at least one of the major parties making little or no effort to appeal to their interests or attract their votes precisely because they perceive that group to be divisive.” In a two-party system, these voters are left with only one viable option, and Frymer and Skrentny argue that “the group is likely to find its support taken for granted and its interests neglected by the other major party’s leaders as well.”

Capture can work both ways. Not only can parties capture certain groups, but groups and movements can capture parties. The Tea Party movement in 2010 successfully captured the Republican party, ousting congressional leadership along the way. And Trumpism has almost completely captured the party today, penalizing and ostracizing any who dare contest it.

In the case of black voters and today’s Democratic party, the capture is the product of three interrelated factors.

(1) Republican leadership views the prioritization of the black electorate’s central policy demand—strong federal civil rights protections—as harmful to its standing with its heavily white base.

(2) As a result, to demonstrate alignment with its base, the party takes positions perceived to be resistant to the policies most desired by black Americans.

(3) The Democratic party, while willing to deliver on some symbolic and expedient measures that appeal to black voters, is not compelled to be as responsive to the demands it calculates to be more electorally costly despite the black electorate’s partisan loyalty.

But let’s say you are a principled conservative looking to recapture the Republican party, then you could turn to the states for inspiration. Republican governors have long fared better with black voters than the party’s presidential nominees, such as when Maryland governor Larry Hogan won nearly 30 percent of the black vote in his 2018 reelection while running against Ben Jealous, a progressive black candidate and former head of the NAACP. Conservative positions on school choice, tax rates, and less regulation on small business, for example, paired with a principled but pragmatic approach to civil rights protections could be a recipe for success for the right candidate in the right moment.

But, proceed with caution: Recently inaugurated Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin—the Republican party darling just a few months ago—is unpopular in the state, with a 41 percent approval rating last month among registered voters. And his outspoken position on critical race theory has run headlong into Virginians’ desire for schools to teach how racism impacts America today: two-thirds of Virginians support this, including the majority of white Virginians.

Given the current state of our politics and the especially divisive rhetoric around race and education in America, this almost certainly is not the moment for Republicans to make inroads with black voters. Moreover, executing a national strategy akin to what some governors have managed in their states is an extremely difficult task given that the party has not demonstrated either any genuine interest in the idea or the capacity to carry it out.

Where does this leave us? Trump’s consecutive subpar presidential performances and Biden’s approval rating among black voters that matches Bill Clinton’s in his first two years are not indications that the black electorate is ready to upend decades of partisan alignment. The leftward lean of Democratic politics could eventually cause a rift on the margins with a pragmatic black electorate. But that is not what we’ve seen over the past 12 years, and in any case, the Republican party is terribly out of position nationally to capitalize on any such developments.