The new film She Said—based on the nonfiction book of the same name by two New York Times reporters about their investigation into the sexual depredations of Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein—marks a milestone that has gone almost unnoticed amid the frenzy of other news: the five-year anniversary of the #MeToo movement sparked by Weinstein’s downfall. Several articles marking the anniversary have revisited the movement and explored its current status and cultural and legal impact. But these retrospectives almost universally left out #MeToo critiques and complications, such as the plight of the unfairly or dubiously accused. A more balanced overview is in order. The #MeToo hashtag was born on October 15, 2017 from a tweet by actress Alyssa Milano in response to the revelations of multiple accusations against Weinstein in the New York Times and the New Yorker. https://twitter.com/Alyssa_Milano/status/919659438700670976 (The phrase had been coined more than ten years earlier as a slogan against sexual abuse by black activist Tarana Burke, whose role was acknowledged by Milano a few days after the hashtag’s first appearance.) The Weinstein reports were explosive. A producer who had been behind some of the most famous films of the 1990s and 2000s, from The English Patient and Shakespeare in Love to the Lord of the Rings and Kill Bill franchises, a man who for years had had the power to make or break an actor’s career, was exposed as a serial predator who had repeatedly paid off women to ensure their silence. The lurid stories included accusations of rape, of using auditions as setups for sexual assault, of extorting sexual favors and punishing the noncompliant. (Weinstein has since been found guilty of third-degree rape and a criminal sexual act in New York; he is now on trial again in Los Angeles.) The reaction was one of nearly unanimous anger and disgust. Weinstein became a symbol of the powerful man using his position to treat women in show business as his sexual playthings. While the #MeToo hashtag invited women to share any experiences of sexual harassment or assault, the stories that got the most mileage were Weinstein-like in that they focused on abuse of power. Allegations that Roger Ailes, the longtime Fox News president, created a toxic workplace and sexually harassed employees became the basis of both a TV series and a movie, while allegations that Louis C.K., the standup comic and actor, indulged in gross sexual misconduct toward women resulted in the cancellation of both a TV series and a movie. And while most of the victims were women, there were exceptions. One of most notable scalps collected by #MeToo was that of actor Kevin Spacey, who was accused of preying on men and, in some cases, underage boys; another fallen idol was Metropolitan Opera conductor James Levine, disgraced and fired after several men came forward with harrowing stories of sexual exploitation when they were teenagers. Each of these men had for years been the subject of rumors and whispers; it took the arrival of #MeToo for the accusations to be treated seriously. #MeToo also unquestionably had a positive impact in puncturing the impunity too often enjoyed in large organizations by men protected not only by status but by the aura of prestige and indispensability. That was the case, for example, with CBS and PBS talk show host Charlie Rose, who, despite several complaints and warnings to managers, remained unscathed until 2018. (The allegations against Rose included walking around naked in front of female staffers and groping their breasts, buttocks, and genitals.)

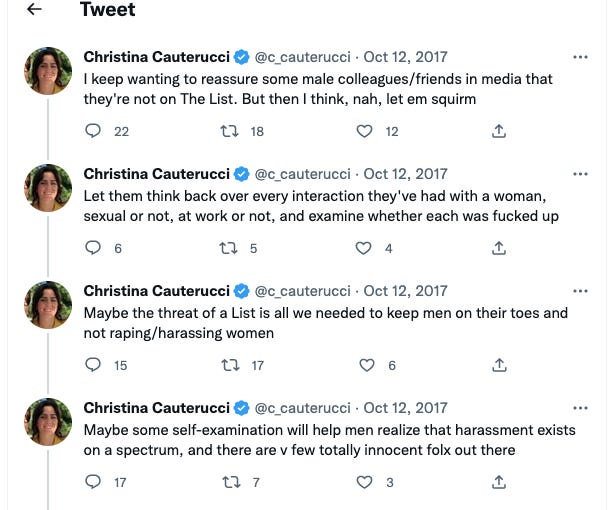

But from the beginning, #MeToo also ran along a parallel track of broadly denouncing men as a group; demanding what Vox’s Constance Grady called a “great reckoning with systemic, entrenched misogyny and sexual violence”; and “canceling” individual men over behavior that was trivial, unproven, ambiguous, or all of the above. Soon after the hashtag started, journalist Moira Donegan created the infamous “Shitty Media Men” list, a Google spreadsheet in which women could anonymously list the names of men they considered guilty of a wide range of misconduct, from rape to “creepy” direct messages on Twitter, “weird lunch dates,” and other sketchy but distinctly non-criminal behavior. Gee, what could possibly go wrong? After the list was predictably leaked and several men saw their careers implode, Donegan herself was outed (or rather, outed herself when reportedly on the verge of being outed). Even many #MeToo supporters, such as Slate writer Christina Cauterucci, expressed “queasy” misgivings about the list—the ease of making unsubstantiated or even malicious accusations, the temptation of conflating predation with obnoxious behavior and petty everyday offenses. Nonetheless, Donegan got widespread sympathy while Katie Roiphe, the dissident feminist who allegedly intended to out her in a Harper’s essay on #MeToo, was widely condemned. In her Vox article a couple of months after the list came to public attention, Grady pooh-poohed concerns about due process for accused men, pointing out that no one on the Shitty Media Men list had faced criminal charges and that those whose careers got wrecked could “plausibly expect” to bounce back, while women who “tried to protect themselves and (some) other women” routinely got “blackballed” and had to live in fear. Donegan seems to be doing fine, though, while some dubiously accused men have never quite come back from it. The degree to which the #MeToo “reckoning” demonized male behavior was evident in Cauterucci’s response to the “Shitty Media Men list” on Twitter.

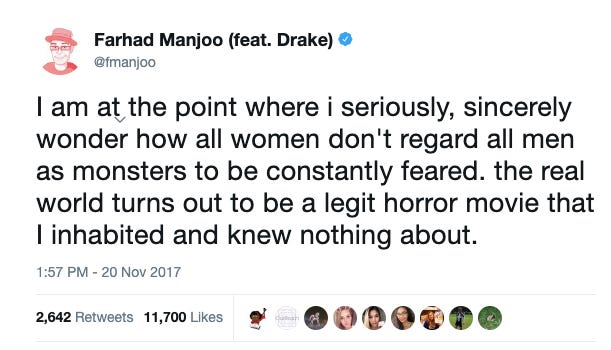

On the male side, New York Times columnist Farhad Manjoo voiced a not-uncommon sentiment in a viral (but later deleted, presumably in a more sober moment) tweet:

But here’s the thing: In the real world, men do not have a monopoly on behaving badly and women do not have a monopoly on victimhood. (This was underscored by the shocking disclosure less than a year after Weinstein’s fall that one of his most outspoken accusers, actress Asia Argento, had her own #MeToo problem: She had made payments to young actor and musician Jimmy Bennett, a former child costar, after he alleged an inappropriate and traumatic sexual encounter when he was underage.) Yes, men are nearly always larger and stronger and generally more sexually aggressive—a legitimate factor in judging interactions between the sexes. But the #MeToo framework as articulated by Cauterucci, Manjoo, or New York Times opinion writer Roxane Gay—who urged men who haven’t been accused to anything to fess up “how they have hurt women in ways great and small,” from lewd comments at work to guilt-tripping a reluctant partner into sex—is a reductive approach that sets up a crude victim/villain binary and demeans both women and men. Ultimately, people hurt people in ways great and small, regardless of sex or sexual orientation—especially in intimate relationships (where personal bonds are more intense and the potential for hurt is much greater) but also in friendships and in professional settings. To be sure, Weinstein-type serial sexual predation is not an equal-opportunity offense, and it would be silly to suggest otherwise; but when you get to lower-level bad behaviors, from unwelcome flirting or irksome sexual humor to manipulation or bullying in relationships, the playing field is much more level.

What happens to this playing field when male misbehavior becomes the target of a political movement? What happens when accusations are viewed through the prism of the belief that it is imperative to “believe women” and that very few men are “totally innocent”? Chances are, things are going to get messy. As they have. #MeToo rose on a wave of wrenching personal stories—stories of women (and in some cases men) sexually exploited, even sexually terrorized, by powerful abusers like Weinstein. But almost at once, other stories began to show up: ones of unsupported, ambiguous accusations, with little if any evidence of abuse of power and with plenty of room for subjective interpretation and fuzzy or distorted memories. For instance, one of the earliest #MeToo allegations in journalism targeted Marxist British writer Sam Kriss, a prolific freelancer who had written for Vice, the Atlantic, Salon, Slate, the Baffler, and the Guardian, among other left-leaning and center-left outlets. In October 2017, a Facebook post by an anonymous woman claimed that while they were on a date, at the theater and then in a pub and at a bus stop, in each case with many people around, Kriss repeatedly kissed her against her will, groped her breasts, and tried to pressure her into coming back to his place for sex. Kriss’s apology, which admitted to “aggression” and “absolutely unacceptable” behavior, revealed a salient detail: that he and his accuser had “an existing sexual relationship”—presumably meaning they had had some kind of sexual interaction during their two previous encounters—and that they been exchanging “intimate[]” messages. No, this doesn’t excuse sexual violence, but it can provide, as Kriss wrote, “some context” for his boorish behavior. By his account, his offense was that he failed to be “properly attentive” and did “not pick[] up on her signals.” The woman’s own narrative could be read as describing mixed signals on her part; she regrets at one point that she didn’t do more to make her objections clearer: “I wish I’d caused a scene.” Their accounts differed as to the incident’s aftermath: The woman claimed that she stayed connected to Kriss on social media only to “avoid any event he might be in attendance at,” while Kriss claimed that she continued messaging him and suggested meeting again until “other divisions” came between them. The woman herself wrote that her decision to come forward was prompted by anger at Kriss’s online posts that she deemed antifeminist and misogynistic. As with many breaking #MeToo scandals, the public reaction was intense. (One sitting member of Parliament tweeted that Kriss belongs in prison.) But were the repercussions for Kriss appropriate for his misdeed? In the half-decade since the airing of the accusations and Kriss’s apology, his work has not appeared in any of the outlets that had previously published him. (His attempts to rebuild his career have apparently been limited to a self-launched Substack and a handful of pieces for, strangely enough, the conservative outlets First Things and the Spectator.) You don’t have to like the man or to defend his boorish behavior to think that, given the full picture, the consequences have been disproportionate to the allegations. Another case of career destruction of dubious merit was that of Jonathan Kaiman, the former Beijing bureau chief for the Los Angeles Times. In January 2018, a female friend who had known Kaiman while living in China tweeted in the #MeToo hashtag to say that she had felt pressured into sex with him five years earlier; as she recounted it, she changed her mind during a consensual encounter and Kaiman “whine[d]” until she came back to bed to placate him. Kaiman denied any pressure but still offered a contrite apology; amid the denunciations, a second woman who had known him in Beijing, fellow journalist Felicia Sonmez, claimed that he had sexually assaulted her during a hazily remembered drunken hookup in 2017. (Both women were upset with Kaiman in the days just after these encounters, but it seems fairly clear that neither of them regarded his behavior as punishable misconduct until long after the fact.) Again, did the price Kaiman paid suit his alleged transgressions? Your answer may depend in part on whether you agree with Sonmez that these two incidents, which the parties recall differently and for both of which Kaiman apologized, establish a “pattern” of sexual misconduct. Kaiman was forced to resign from the presidency of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China and fired from the Los Angeles Times. He became, as he told writer Emily Yoffe, “radioactive” in the field; his Twitter bio indicates he has left journalism. Other #MeToo cases involved stories that are even less clear-cut.

Fired Mic writer Jack Smith IV is still in exile after a lengthy piece on the feminist website Jezebel in October 2018 exploring the “gray areas” of #MeToo convicted him, as Katie Herzog put it in the progressive magazine the Stranger, of being a “bad boyfriend.” (The charges were almost entirely of “emotional manipulation,” though an ex-girlfriend also claimed that he once wrapped his arm around her neck during sex tightly enough to restrict her breathing; for what it’s worth, Smith adamantly denied the choking allegation and no other woman reported anything remotely similar.)

Evan Stephens Hall, the lead singer of the indie rock band Pinegrove, was hit with a vague accusation at the height of #MeToo, in November 2017, from a crew member with whom he had been briefly involved. The woman had come to see the relationship as coercive; she acknowledged that Hall had no power over her—she did not rely on the band for income, and it had an unstructured, egalitarian atmosphere—but said that she “really felt like he did.” The band canceled a tour, delayed the release of a finished album, and went on hiatus for the better part of a year. (The band’s comeback was later disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic.)

In the case of comedian and actor Aziz Ansari, every excruciatingly awkward detail of a failed effort to have intercourse with a woman after a 2017 date was recounted by the woman in a cringe-inducing post the next year on the short-lived website Babe.net. Ansari denied that anything nonconsensual happened and voiced his support for #MeToo, and while he faced few noticeable professional repercussions—he continued to tour and to produce his Netflix specials and series—had had to undergo the humiliation of having a private, intimate encounter publicly dissected and debated, criticized and mocked.

And then there are the men whose #MeToo-ing did not involve any charges of sexual contact at all. Veteran public radio host Leonard Lopate was fired by New York’s WNYC for mild off-color jokes that some employees found offensive, such as telling a female producer working on a cooking segment that “avocado” came from the Aztec word for “testicle” or making a quip in poor taste—“That’s how I treat my staff”—while discussing a story about sexual slavery. Lopate later found refuge at far smaller station, WBAI. Sometimes, even being formally cleared does not quite remove the stigma. In 2018, writer Zinzi Clemmons accused renowned novelist Junot Díaz of “forcibly” kissing her after a campus literary workshop when she was a graduate student; two other female writers came forward to back her, claiming that Díaz had subjected them to misogynistic verbal abuse at public events. Díaz categorically denied Clemmons’s allegation. One of the accusations of verbal abuse, from novelist Carmen Maria Machado, fell apart after the release of an audio recording which showed that Díaz’s perfectly civil, if slightly exasperated, response to Machado’s hostile question was nothing like the terrifyingly aggressive rant she described. (It’s hard to tell whether Machado knowingly lied, as many assumed: she had mentioned the existence of an audio recording in her original Twitter thread, presumably thinking that it would back her up. More likely, her perception was skewed by ideological filters: She told New York magazine’s Vulture blog that at the time of her run-in with Díaz, she had begun to “radicalize” as a feminist and “had a super-tightened awareness, a heightened level of anger, and an increased sensitivity to male bullshit.”) The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where Díaz taught, and Boston Review, where he served as fiction editor, investigated Díaz and found no substantiated misconduct. Yet these organizations’ refusal to cut ties with him was met with an angry outcry; three Boston Review editors resigned in protest. The novelist’s third accuser, playwright and novelist Monica Byrne, went on Twitter to claim that 38 women had contacted her with “firsthand, secondhand, or hearsay” reports of sexually abusive behavior by Díaz, but that she could not identify them because of confidentiality. Vox reported the story in a way that implied Díaz was a bad actor who’d gotten away with it. Despite his exoneration, his books were dropped by many independent bookstores and cut from college curricula, causing his sales to plummet. He remains at MIT but is no longer on the Boston Review masthead and has kept a fairly low profile ever since the scandal.

The individual stories, famous and obscure, can be endlessly discussed. Some are relatively straightforward: The accusations of sexual aggression and bullying against former CBS chief Les Moonves, for instance, came from more than a dozen women, many of whom had told friends and colleagues about their humiliating and frightening experiences with Moonves years earlier. Others are far more complicated. Did writer and public radio host Garrison Keillor deserve to have his work memory-holed—to the point where he had to sue to get his archives back—because of a past romance with a staffer at a time when such relationships were reportedly a normal thing at the station (plus complaints of nonsexual crankiness toward subordinates)? Should the great tenor Placido Domingo have been cast out of the American music world over accusations of inappropriate behavior that ranged from flirting to sexual advances toward adult women—with most of the accusers anonymous, and with no clear evidence that any of them suffered professional repercussions for rejecting him? The specifics of such cases can be endlessly debated and nitpicked. But finally, the reality is that most of the time, sexual dynamics are tangled and complex, especially when seen through the prism of two individuals’ different subjective experiences. People who flirt, engage in sexual banter or humor, or initiate romantic attentions may often fail to see the extent to which these behaviors are unwelcome, mistaking reluctant tolerance for reciprocity or missing subtle signals to stop; but those on the receiving end of such attentions may also retroactively underestimate the degree of reciprocity. I am deliberately keeping this gender-neutral; but the rhetoric around #MeToo often assumes that sexualized dynamics in work-related settings are virtually always initiated by men and that women at most acquiesce because they either are powerless or socialized to coddle men’s feelings—a simplistic assumption that denies not only female agency but female sexuality. It is also, in many cases, an assumption belied by the facts. At the height of #MeToo, in December 2017, a New York Times article about sexual harassment charges against restaurateur Ken Friedman featured a striking comment from one of Friedman’s accusers, former restaurant wine director Carla Rza Betts: Betts said she loved the industry’s “grab-ass, superfun late-night culture” and “sexualized camaraderie,” but also stressed that “predation” was different. Fair enough; but surely the lines can be blurred (to quote the title of a song at the center of a #MeToo-like controversy before there was #MeToo), and misperceptions and mixed signals can happen. What’s more, today’s “fun” and “sexualized” camaraderie can be reinterpreted as “predation” months or years later. People, after all, not only consciously rethink their past experiences but routinely and unconsciously revise or “edit” them, particularly when there is an emotional incentive to do so—a relationship or friendship that has soured, or a cultural climate that invites such revisions. Memories get filtered through personal and ideological biases and grievances. And so thorny questions abound. Should all workplaces have the same norms and standards when it comes to flirting or sexual banter and humor, or should we make allowances for a diversity of workplace cultures even if it means that some people will find the climate in some workplaces uncomfortable? Should our judgment of alleged misconduct by artists in various fields take into account the fact that they work in an environment in which they themselves are frequently sexualized and pursued by fans? Should an artist who deals with sexual subject matter be off the hook for things that would be wildly inappropriate in other contexts? Was the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. being progressive or philistine when it canceled a 2018 exhibition of the work of photographer Chuck Close—known for his nude portraiture of both women and men—over misconduct charges from eight women who were creeped out by Close’s comments during nude photo shoots, or disappointed when they realized his offer to photograph them involved nudity?

The question of partisan politics and the political uses of #MeToo throws another wrench into these debates. In a way, #MeToo itself was deeply political, and not just in the sense of sexual politics. Its birth was in large part a reaction to Donald Trump’s election victory after the infamous Access Hollywood tape in which he boasted about being able to “do anything” to women, including grabbing their genitals, thanks to his celebrity status—and after a string of sexual misconduct allegations. Yet, ironically, Trump remained largely unaffected by these allegations, while the #MeToo movement targeted primarily liberal men—starting with Weinstein himself, a major Democratic donor and Hillary Clinton supporter. Indeed, the two biggest political scalps #MeToo collected both belonged to Democrats: Sen. Al Franken of Minnesota and Gov. Andrew Cuomo of New York. What’s more, both cases leave plenty of questions about whether the takedown was justice or witch-hunt. Franken, whose troubles began with a prank photo from his days a comedian in which he mimicked groping a female performer’s breasts, resigned from the Senate in early 2018. A year and a half later, he was fairly conclusively exonerated in a thorough report by New Yorker reporter Jane Mayer. (The Franken case is also a classic example of why context matters: The photo was taken at the end of a USO tour filled with bawdy banter and horseplay in which Franken’s accuser, Leeann Tweeden, had willingly participated; apparently, it also referenced a skit she and Franken had performed together.) The case against Cuomo, which began with a single accusation from an ex-staffer and by the time of his 2021 resignation had snowballed to include several more, is complicated, and is the subject of still-pending litigation by a former New York state trooper who has complained of inappropriate touching. At the very least, however, some of Cuomo’s most visible accusers have serious credibility problems, and all of the criminal complaints filed against him have been dismissed. #MeToo accusations against then-Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh in the fall of 2018 failed to sink his nomination but further exacerbated America’s culture-war fever. Then, in 2020, #MeToo came for presidential candidate Joe Biden, at first accused of inappropriate hugging and touching (which he and his supporters defended as a gender-neutral, physically affectionate style of interacting with the citizenry) and then of sexual assault on a staffer named Tara Reade, allegedly committed many years ago. As the accusation threatened to derail Biden’s campaign, the Public Broadcasting Service and Politico ran devastating pieces debunking Reade’s claims—and, many felt, striking at the foundations of #MeToo with its #BelieveSurvivors principle. When actress and #MeToo activist Alyssa Milano, who had earlier tweeted about standing with Kavanaugh accuser Christine Blasey Ford, tweeted during the Biden scandal about the need to vet accusations and give due process to accused men—

There is something to the idea that people are going to weaponize #metoo for political gain. Just look at the replies here and look to see who those accounts are supporting in the primary. There always needs to be a thorough vetting of accusations.

— Alyssa Milano (@Alyssa_Milano) April 6, 2020

—critics saw not only hypocrisy but the self-inflicted death of a movement, in much the same way that the Democrats’ willingness to shrug off the Bill Clinton/Monica Lewinsky scandal in 1998 stopped the momentum of the movement against sexual harassment that began in 1991 with Anita Hill’s accusations against Clarence Thomas. Cuomo’s downfall last year showed that the #BelieveSurvivors mindset was still going strong in Democratic circles, at least when the presidency wasn’t at stake. Nonetheless, concerns about the political weaponization of #MeToo—and about double standards—are likely to remain.

What, then, to make of #MeToo five years later, when the movement has been partly eclipsed by other progressive causes such as racial justice and transgender rights but still continues to have an impact? It is perhaps worth recalling that, contrary to fashionable narratives, #MeToo did not in any real sense break the silence about sexual harassment and sexual violence, or bring those issues out of the shadows. Even leaving aside the feminist activism of the 1990s, and to a lesser extent, the two preceding decades, the modern wave of feminist activism heavily focused on male victimization of women began circa 2013 with the notorious high school sexual assault case in Steubenville, Ohio, and then gathered strength with the misogyny-driven 2014 shooting spree in Isla Vista, California and the subsequent #YesAllWomen Twitter hashtag. There were plenty of fairly high-profile accusations of sexual assault or misconduct before #MeToo—both ones in which victims finally got a well-deserved hearing, as with Bill Cosby’s fall from grace in 2015, and ones in which the accused got a raw deal. #MeToo turned this momentum into a tsunami that swept away some of the machinery protecting the powerful, but also needlessly wrecked lives and reputations. On the positive side, it exposed some high-status abusers such as Weinstein, Levine, and Rose, and ended the near-impunity enjoyed by millionaire predator Jeffrey Epstein even after his prosecution for sexually abusing a minor. Individual cases aside, #MeToo deserves great credit for having drawn attention to the problem of powerful predators who act as though they see their female employees (and in some cases, male ones) as their personal sexual property. On the negative side, there are the problem cases discussed here, as well as many others (including some that have ended in the suicide of the accused). There is the posthumous trashing of the novelist and short story writer J.D. Salinger, based on an account by former girlfriend Joyce Maynard that turns out to have major inconsistencies with her own earlier versions of the story. There is the hostility toward art that is seen as sexualizing or “objectifying” women. There is the blanket male-bashing rhetoric and the drive to politicize and “problematize” all male/female sexual dynamics. This is not to say, of course, that traditional norms of sexuality—whether in art or in life—should not be questioned or challenged. But there is a difference between “questioned” and “conflated with abuse,” and one can challenge traditional norms by exploring and encouraging new ones instead of demonizing older ones. To be sure, some critiques of #MeToo excesses have themselves been guilty of excess. That includes an early manifesto signed by a hundred French female artists and intellectuals, including actress Catherine Deneuve, and characterized as “stunningly silly” in a column in the Guardian by writer and academic Laura Kipnis, herself a dissenter from feminist sex-policing. Among other things, the manifesto suggested that even the most persistent unwanted advances or “sexually charged messages” should not be treated as an offense and that a stranger rubbing against a woman on the subway is no big deal. Yes, it’s impossible to regulate all unwanted sex-related interactions out of existence without stifling much wanted sexuality; however, just because it would be absurd to lower the speed limit to 20 mph and force drivers to stop at every traffic light doesn’t mean that we should raise it to 120 mph and get rid of red lights altogether. For the moment, the conversation about sexual abuse, sexual freedom, and sexual ethics has taken a back seat to other pressing issues. Here’s hoping that when this conversation resumes, it will be kinder, more balanced, and more nuanced.