Avatar: The Way of Water is like almost nothing you’ve ever seen before in a very literal way: the combination of high frame rate (HFR), 3D, and 4K projection you’ll see it in via an IMAX or Dolby-branded theater is, simply, different from your normal big screen outing. It’s a sui generis sort of viewing experience, unless you happen to be one of the 12 people who watched Ang Lee’s Gemini Man in 3D HFR IMAX.

What does all this mean? You’re probably familiar with 3D and 4K, as there’s a decent chance you own a 4K TV and you have probably seen a movie or two in 3D in theaters. But “high frame rate” is the game changer here and it’s the thing people will notice the most when they sit down to watch Avatar: The Way of Water. A brief explainer: Once upon a time, “film” was actual celluloid lit by a bright light and run through a projector with 24 static frames running past the light every second to create an illusion of motion. This illusion is what we think of when we think of a “cinematic” image; it’s the (well, a) reason that movies look different from real life, because each second you watch something on screen information—the stuff that happens in between each static shot—is lost.

“High frame rate” means more frames per second are shown to audiences. This means that a.) less information is lost but also b.) it looks, well, different. Which has led some folks to describe HFR as either the “soap opera effect” or “akin to motion smoothing.” This is wrong for several reasons—one of them being that motion smoothing is essentially creating information, which is why our eyes consider it to be uncanny valley-esque—though I understand the complaint.

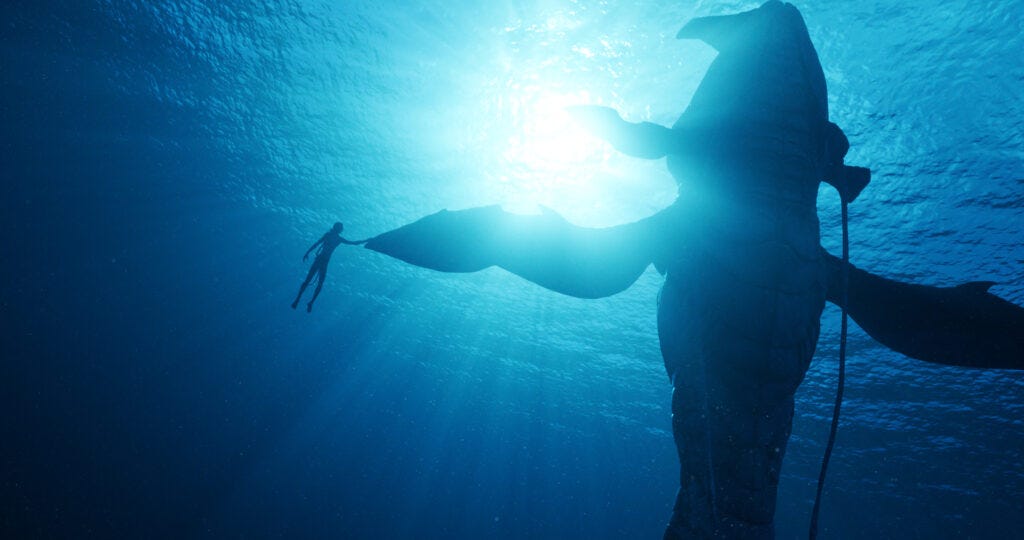

Understand, but dismiss: The combination of HFR, 3D, and 4K projection onto a massive screen with a delicately booming surround-sound cocoon creates an immersive experience that is, frankly, unmatched in my experience. Yes, it looks different—and I understand folks who are frightened by things that are new and different; I am frequently one of them—but the difference is in service of attempting to bring people fully within the proscenium of the screen. James Cameron is bringing you into a new world, one with giant blue cats who talk to whales in order to stop human beings from defiling the land and murdering said whales to steal their precious, immortality-granting brain juices.

I’ve focused on the viewing experience thus far because Avatar: The Way of Water really is an experience as much as a piece of narrative storytelling. As narrative storytelling, I could level a series of complaints: it’s probably an hour too long; the broader goals of the human antagonists are bit fuzzy and scattered; I literally laughed out loud once or twice at some of the New Age mumbo jumbo, because there’s something inherently funny about watching a giant blue alien tell a whale about his feelings while the whale is like “yeah I feel you bro I too am sad.”

Like its predecessor, The Way of Water’s plot is less important than its pictures, though I do think this sequel improves on the original in two key ways. The first is that we have more reason to care about Jake Sully (Sam Worthington) and his struggles: as this film begins we see he has become a father in addition to the leader of his Na’vi tribe. It is his desire to keep those children safe from the Marines hunting him for leading an insurgency against the human colonizers that informs his decision to move the family halfway around Pandora and blend in with the island tribes of Na’vi who live on the water rather than in the forests.

The marines in question are the second improvement, as Col. Quaritch (Stephen Lang) returns from the dead in the form of an avatar—that is, a cloned Na’vi body into which his consciousness, recorded hours before his death in the original, has been transferred—to do battle with his nemesis Jake Sully. Quaritch remains a cold sonofabitch but Cameron has given him a son as well, a baby left behind on Pandora when the humans fled: Spider (Jack Champion) is basically a half-brother to Jake Sully’s kids, and Quaritch, admiring the boy’s toughness and skill, hopes to reclaim him for humanity.

As such, Quaritch is very slightly less cartoonish in his villainy this time around. For instance, at one point Quaritch is searching a Na’vi village for Jake Sully and his family, burning huts and detaining locals while the two sides yell at each other in different languages. The Vietnam parallels are clear—you can practically feel Cameron straining against the desire to show Quaritch and his comrades do a My Lai—but the officer holds back, worried that an outright massacre will cost him the love of his son. So, instead, Cameron pours his cruelty into the capture and slaughter of a whale-like creature whose secretions grant immortality. Like ambergris for the soul.

For all the world-building we see on Pandora—and we see a great deal of it, particularly in the middle hour that can only be described as a travelogue to a distant planet—the motivations of the human colonizers are woefully underexamined. We learn that Earth is dying so Pandora will need to be remade for humans and it’s just a single tossed-off line. We learn about the immortality juice but have no idea how the humans discovered this or how they created a whole whaling operation in the short time they’ve returned to the planet. Frankly, we have no idea if Pandora is the only planet humans have traveled to and are colonizing. Is this the one and only hope for the future of humanity? Who can say. Maybe we’ll find that out in Avatars 3-5, hitting theaters soon.

Anyway: the whales. There’s something admirably goofy about Cameron’s commitment to the bit here, the communing between Na’vi and pods of Pandora whales, the suggestion that the whales have evolved a philosophy of nonviolence and will willingly go extinct rather than fight against their own slaughter. (Pacifism: not even once.) It would take a heart of stone not to giggle at the silliness of it all, and yet the engrossingly immersive nature of the 3D cinematography here makes the almost entirely unnecessary middle hour or so of this movie less slog than sojourn.

My one complaint about the use of HFR in this film is that Cameron switches back and forth between 48 fps and 24 fps, sometimes from shot to shot within a sequence, for no good reason. The effect is disconcerting and, ultimately, degrading to the immersive nature of the viewing experience; it reminded me of Christopher Nolan’s constant switching between IMAX film and regular film in Dunkirk, which was similarly distracting. Nolan had the excuse that he couldn’t shoot everything on IMAX; Cameron shot everything in 48 fps and decided shot to shot which should be slowed down to standard 24 fps. The result is terribly distracting, a constant reminder that you’re watching a movie.