Beethoven at 250: Four Masterpieces to Celebrate the Big Day

From mysterious to manic, a small tour of the great composer’s works.

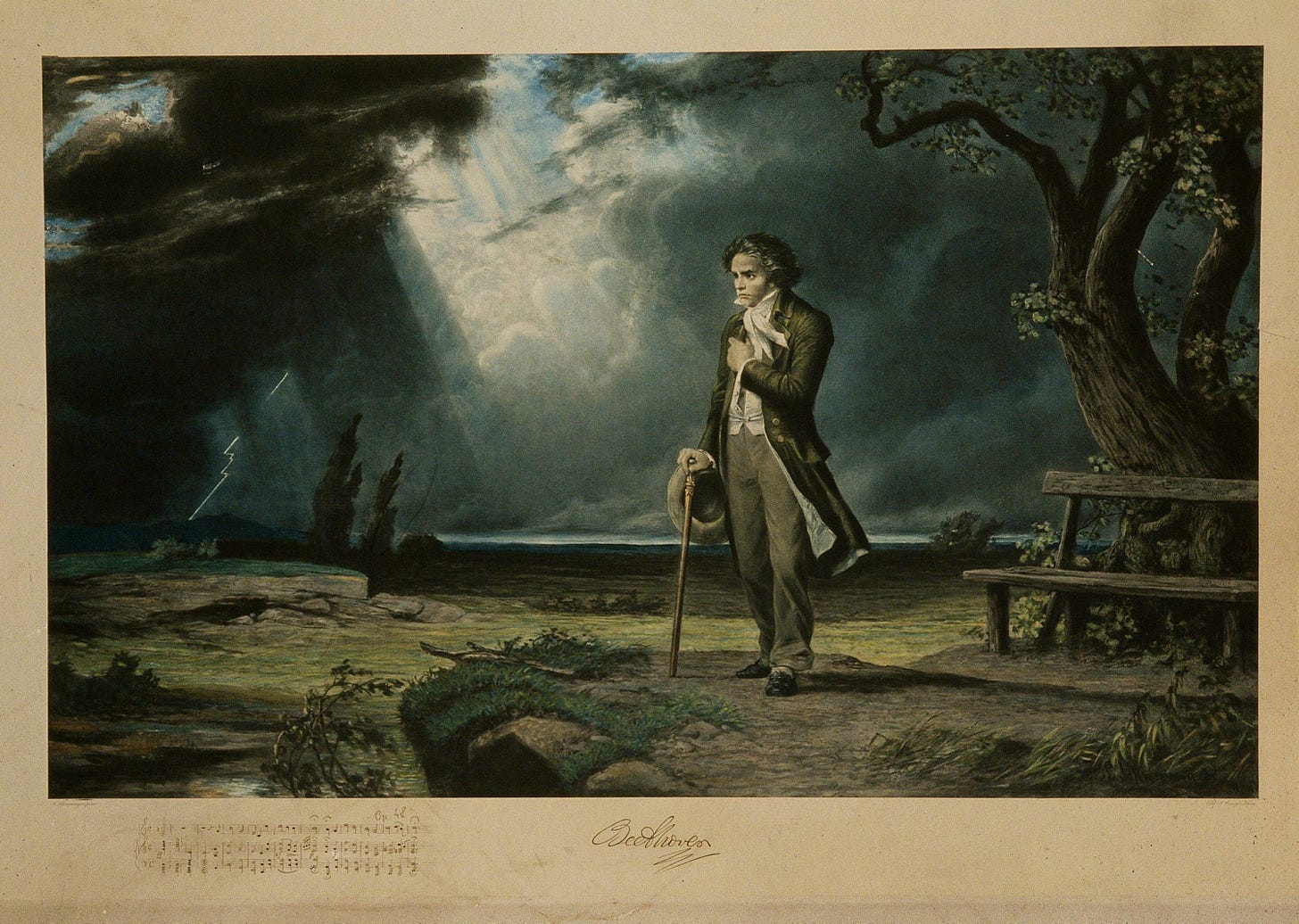

Among the countless COVID cultural casualties has been the big Beethoven birthday bash. The 2020 calendar is jam-packed with canceled concerts and commemorations of Ludwig van Beethoven’s sestercentennial. We don’t know for sure the date of his birth, but we know from church records that today, December 17, is the 250th anniversary of his baptism. He was likely born a day or two earlier, so we can think of this as his birthday week.

In lieu of a global gala, how can we best celebrate the great Bonn-born master who didn’t just change the course of music but changed the course of history?

I’m sitting alone at a desk in rural New Hampshire watching snow cover the grand pine trees and I dreamily transport myself to the concert hall: Putting on my tails and tying my white bowtie, checking over my cello and bow to make sure everything is in order before walking on stage, flipping through the music to remind myself of any tricky turns or moments of special delicacy that need attending to, the lights dimming, the conductor entering, the music starting. Waves of earthy tones written down two centuries ago sweep over the audience and the orchestra as we are gripped, willingly or unwillingly, by the force and the magnetism of the music. . . .

“Okay Dan, enough,” I tell myself, my charming simulation over. It’s 2020: no big concerts, no live audiences. But as I listen to Beethoven here at my desk, the power of the music remains undiminished—and I want to tell you about a few of his works that I really love because I think his spell is going to work on you too. I won’t tell you what these pieces should mean to you, though: Great music is great in part because it has both a collective message and infinite personal messages. I have picked extraordinary recordings to go along with the works here, and I hope you’ll listen and love these as I do. So I invite you to take a little tour with me through a few of Beethoven’s great pieces, and who knows—maybe 2021 will end up being your Beethoven year.

String Quartet No. 9 (Op. 59 No. 3)

For the string quartet—an ensemble of two violins, a viola, and a cello—Beethoven wrote sixteen pieces, starting early in his career and finishing the last in 1826, just months before his death. The first movement of this 1806 piece, which has been a favorite since I was a kid, starts off with strange-sounding chords, extremely slow. Mystery meets melancholy. Then, after a minute and a half, suddenly, as only Beethoven can do—hope! The slow introduction is over and we are launched into one of the greatest jaunty, upbeat movements Beethoven ever wrote. It’s unabashedly fun, it’s lighthearted, it’s carefree. A wonderful example of the almost symphonic world that he could create with just four instruments.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OWnzalQhH1s

Symphony No. 6 Pastoral (Op. 68), movements IV and V

Speaking of symphonies, we’ve lately been hearing a lot about the famous Fifth, and of course everybody seems to know the Ninth, with its glorious choral finale. But I want to take you to Symphony No. 6, one of the few pieces Beethoven ever wrote with a “program”—that is, music that represents specific things and has a story attached to it, rather than just being “pure” music. Each movement of the Sixth has a title, and I want you to listen to the last two movements, titled “Thunder, Storm” and then “Shepherd’s song. Cheerful and thankful feelings after the storm.” (Start at 34:27 in the video below.) The storm is scary, violent, and dark, with brooding rumblings from the low strings and thunder created by the percussion section. But its tense mood dissipates rather quickly, and what follows might be single most beautiful movement in any Beethoven symphony. The stereotypical image of a wild, crazy, manic Beethoven couldn’t be farther from this music. This is gentle and warm, true peace put into music that can be heard best in the context of surviving a great storm—and finding the calm after.

https://youtu.be/10rCIZ9TECY?t=2067

Piano Sonata No. 29 Hammerklavier (Op. 106), movement I

If you wanted the manic and wild Beethoven, here he is. The so-called Hammerklavier is gargantuan, but I want to focus here on the first movement. If you listen to thirty seconds and think to yourself “What the hell is going on here?” don’t worry, you’re not alone. The piece, written in 1817-18, long baffled listeners and was deemed totally unplayable due its immense technical difficulties.

Listen for the jarring mood shifts, the key shifts, and the aggressiveness of the volume modulations. You’ll have the feeling that suddenly you’re in a different piece, as if Beethoven shifted gears so radically that the one piece ended and another began! Don’t worry—it’s all one. This piece can seem intimidating, but if you feel that, you’re in good company. It’s one of the great, ambitious movements ever written for a solo instrument. It’s tough to listen to—but listen a second time, then a third. I guarantee it will resonate with you more with each successive hearing.

Missa Solemnis (Op. 123), Sanctus

Beethoven composed two settings of the Catholic mass; this, the second, he finished late in his career, in 1824. He was by then completely deaf (as he was when he wrote the Hammerklavier), emotionally alone, and cut off from society. Some fine musicians I know believe the Missa Solemnis to be the greatest musical work of all time, period. It’s a huge work, but I’m thinking about the Sanctus movement and its Benedictus, only about fifteen minutes of music, where Beethoven goes places no one else went before or since. Just listen to the first minute or so of the Sanctus (starting at about 45:40 in the video below). Can you believe any one person actually wrote this, let alone someone who was completely deaf? It is mind-boggling.

The main part of the Sanctus movement, the Benedictus (starting at 49:40 in the video), is where Beethoven’s incredible ingenuity is on full display. Like a normal mass, we have here a chorus, orchestra, and four solo singers—soprano, alto, tenor, and bass. But in this movement, that’s not enough for Beethoven. He needs a vehicle to rise above even the highest range of the soprano soloist, and so he selects a solo violin (starting at 51:40), giving it some of the most stunning lines ever written for an instrument playing alone in the orchestra. The violin, in concert with the soprano but playing in a much higher range, leaves the singers earthbound as it climbs ever closer to the heavens. This violin solo, one of the great creations in music, is Beethoven ascending to the cosmos. We listeners—believers and nonbelievers alike—are left in awe.

Think of this as a lightly guided audio tour. Of course there’s nothing exhaustive about this list of four excerpts of very different pieces, but I think when you listen you will be struck not just by the variety and depth of these works, but also by how immediately and urgently they speak to us in 2020. The best person to make the case for the importance of this music is the composer himself. Beethoven didn’t get the year-long birthday celebrations he deserved, but maybe when your life needs a little more celebrating, he will be right there for you.