‘Belle de Jour,’ an Un-Erotic Masterpiece

Luis Buñuel’s surreal film maintains its power 55 years on.

One of the only productive things I did over the last couple years of isolation was watching movies—specifically older, influential, “important” ones I am intimidated by (a truly silly notion since they’re not going to insult my children or say my house is messy). I consumed multiple Godard, Truffaut, Kubrick, and Fellini movies in HBO Max’s wonderful film catalog with gusto. Which is how the algorithm delivered me to Luis Buñuel’s Belle de Jour.

I’d heard that Belle de Jour (1967) was an erotic masterpiece. After watching it three times, I only halfway agree. It is absolutely a masterpiece, but it is not erotic. Belle de Jour’s producers, Raymond and Robert Hakim, were famous for making sexually suggestive films. They approached Luis Buñuel to adapt and direct the movie based on the novel by Joseph Kessel, but Buñuel agreed only if he were given complete creative control. The result is a sublime tragi-comedy and an indictment of the bourgeoisie. But it is definitely not titillating.

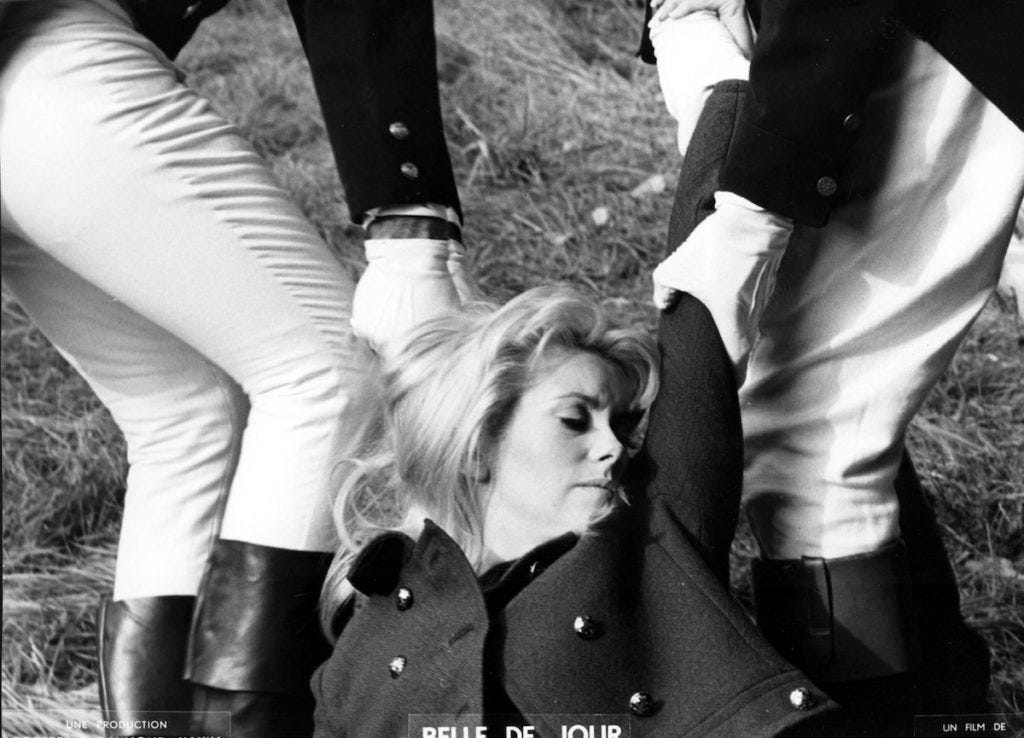

Belle de Jour is about a beautiful, aristocratic young woman, Séverine Serizy (Catherine Deneuve) who won’t consummate her marriage to her impossibly handsome doctor husband, Pierre (Jean Sorel). Instead, she has dreams of total sexual degradation at the hands of Pierre and other men. After hearing about another wife in her social circle who is secretly working as a prostitute, Séverine becomes obsessed with the idea for herself. Husson (Michel Piccoli), a distasteful and mysterious acquaintance, drops the name and address of a brothel he used to frequent. Séverine leaves her tony eighth arrondissement apartment to search for the brothel in a distinctly proletariat section of Paris. After a tentative start, she begins working there in the afternoons. The madam, Anaïs (Geneviève Page) gives her the alias “Belle de Jour” (“beauty of the day”) since she can only work afternoons while her husband is at the hospital. Thus begins her double life: the perfect, if chilly, bourgeois wife to Pierre at night; the blooming, liberated woman Séverine becomes during the day at Madame Anaïs’s whorehouse.

There is no actual sex in Belle de Jour. There isn’t even any real nudity. Séverine’s fantasies aren’t alluring. They’re unsettling and repellent, revealing a woman with an unhealthy, bifurcated spirit: horrifying daydreams that nonetheless thrill her (and that she doesn’t fully disclose to her husband), contrast with her waking life of idle, meaningless beauty and boring consumerism.

The undercurrent of absurdist—and sometimes even slapstick—humor further keeps audiences off balance. Madame Anaïs’s client, “the Professor,” dresses up like a bellhop and becomes angry Séverine doesn’t immediately understand the masochistic roleplay he desires. The butler of a mysterious (and no doubt imaginary) duke wears sunglasses even though he’s indoors and has a querulous relationship with the nobleman, as if they were an old married couple rather than servant and master. Both the Professor and the butler seem like characters out of a sex farce rather than an erotic drama.

Séverine’s fantasies typically involve cats. When rough-looking footmen have their way with her at Pierre’s insistence, she screams, “Don’t let the cats out!” There are the cows with cowbells “named after cats,” whose cow pies Pierre and Husson throw at her as she is tied to a stake. The Duke, before he proposes their tryst, tells Séverine, “I had a cat named Belle de l’Ombre (beauty of the shadows),” a play on her professional name and allusion to his particular morbid kink. As she lies naked but for a black veil in the coffin, The sounds of fighting cats—or, possibly, cats having sex—screech in the background. The butler asks, “Shall I let in the cats?” and the Duke hisses back, “To hell with your damn cats!” Even after majoring in English in college, I cannot figure out the symbolism of invisible wailing cats. The only thing I feel certain about is that Buñuel intends the juxtaposition to be darkly funny.

I’m going to change tone dramatically: In the many articles and reviews I’ve read in preparation to write about Belle de Jour, none mentioned Séverine was molested as a child. Well, one male writer did, but he said it was “a distraction.” Her sexual assault is intrinsic to the film and it is yet another reason I cannot think of this movie as erotic. It’s common for those who have experienced sexual trauma as children to repress and disassociate from their sexuality. This is why Séverine cannot be intimate with her husband except in fantasies where he is punishing and degrading her. She has been frozen in time psychologically to the age when the molestation occurred.

After her friend tells her in a taxi ride about someone they both know who is turning tricks, Séverine is in a daze. She looks lost as she climbs out of a taxi, her arms full of luxury items from a shopping spree. Back in her apartment, she breaks a vase of red roses Husson had sent to her. In her boudoir, she accidentally knocks over an expensive bottle of perfume and it smashes to the floor. “What’s the matter with me today?” she asks in distress. Immediately afterward we see a middle-aged man encircling and kissing a young girl in a refined parlor room. He looks much like the taxi driver who has just told Séverine about his experience driving men to secret Parisian whorehouses. Her mother's voice offscreen yells, “Séverine! Come quickly! Are you coming or not?” The scene is brief, but it is indelible and disturbing. Young Séverine is in knee socks and a school beret. She can’t be more than 12, the age when a girl is beginning to discover her sexuality. The man in dirty blue work coveralls is working class in her parents’ employ. Her eyes are closed. We don’t know if this scene has happened many times or just once, and we also don’t know if Séverine is scared, confused or excited. And how can she know? She’s just a little girl.

Wrestling with whether to work for Anaïs or not, Séverine sits on a bench in an elegant park and watches schoolgirls happily and innocently jump rope. In a later scene, one of her Johns comes on to the teenage daughter of the brothel’s housekeeper—in knee socks and school beret—echoing Séverine’s adolescent trauma. The duke, as she cosplays his dead daughter, says, “I hope you have pardoned me. It wasn’t my fault. I loved you too much.” Séverine is beholden to her dark scars. And she thinks the abuse is her fault. She represses her feelings except in salacious daydreams. It is why she is both attracted and repulsed by Husson’s lasciviousness, why she wants to be dominated by anonymous strangers, men who are frequently repellant and not of her social milieu.

The tension between her bourgeois upbringing and her secret desires are what attract her to the dangerous, reckless criminal, Marcel (Pierre Clémenti, in an incredible performance). Marcel is all animal instinct. Feral, in fact. He is tall and rail thin, has fake gold teeth, and is a flamboyant dandy: long, leather coat, velvet suit, hip-slung belt, shiny buckled boots and a walking stick. As if Lord Byron were a petty thief. He has cheekbones that could cut glass and a stare that sees right through Séverine’s fake placidity. He stalks around her, examining her up and down as if she were a prize breeding mare. He is cruel on purpose, testing to see how she will react. There is a strange, savage elegance to him. He moves like a dancer. He is undeniably alluring. And his arrogance is a front for his vast insecurity and vulnerability, a feeling of being alone and adrift in the world.

Again, we never see Marcel and Séverine have sex, but Buñuel does have a closeup of his legs on top of hers. Her patent leather, Yves St. Laurent shoes beneath his feet as he pushes off his patent leather boots and reveals dirty socks with holes underneath.

Buñuel and his co-writer, Jean-Claude Carrière, paint Séverine and Marcel’s daytime trysts as more than just sexual. They are oddly romantic. He loves her in his own treacherous way. And she refuses to charge him for sex even before they’ve had it; afterwards, her hands tremble. “You scare me,” she says. Marcel is the antithesis of selfless, harmless, Ken-doll-good-looking Pierre, and that’s what Séverine can’t resist. Marcel is the dark, lowlife Romeo to her Juliet. We understand why they are tragically drawn to each other. They have genuine chemistry. But Séverine knows their pairing is unhealthy and unholy. She says to Husson, when he discovers her at the brothel, “I’m lost. I know I’ll have to answer for it one day. But I couldn’t live without it.”

And of course, Séverine is right. Marcel’s obsession with her culminates in the attempted assassination of Pierre, paralyzing him, blinding him, and rendering him mute. The police then kill Marcel. Cut off from both her light and dark lovers, she becomes a chaste, dutiful wife again. In her black A-line dress and pious white collar (dressed like a “precocious schoolgirl,” as Husson taunts), she feeds her husband medicine while he sits immobile in a wheelchair, dark sunglasses covering his unseeing eyes. She finally feels whole. She’s expiating her guilt by serving him for the rest of their sexless lives. “Ever since your accident, my dreams have stopped,” she tells him. This is her warped version of Happily Ever After.

Until, that is, Husson comes to see Pierre to tell him about Séverine’s double life. He claims it’s so Pierre doesn’t feel like a burden to the perfect wife he assumed he had married. But it’s truly to punish Séverine. Husson is merely a sadist. He has become the real life torturer he was in her fantasy when he threw cow shit on her and called her a slut.

As the clock chimes five—the hour she used to return home from the brothel—she re-enters the living room where Pierre sits in helpless misery, tears running down his cheeks. She sinks back into the couch. All of a sudden she hears the cow bells again. Pierre takes off his glasses, smiles at her, and rises out of his wheelchair. The cats screech. He and Séverine toast each other, they hug, they chat about where they might go on vacation. And then we hear the horse-bells. Séverine walks out onto her Parisian balcony, and all of a sudden she is back in the country where the first scene took place, the black horse and carriage with the gangster-footmen riding beneath her.

What is real and what is fantasy? Has she divided once again? At what point do Séverine’s masochistic daydreams become her real life? Was the whole movie in her head? Did any of it really happen? Is Séverine a living person or is she a symbol? Is she a victim, a heroine, or a villain? Rather than a tale of eroticism, Luis Buñuel and Jean-Claude Carrière intend Belle de Jour to be a fable without a moral, a dark fairy tale, a pitch-black Cinderella: Anaïs (or maybe Husson) as a perverse fairy godmother, two handsome princes and even a horse-drawn carriage. Depending on which interpretation we want to cling to, either Pierre’s tears release him from an evil spell or Séverine escapes the misery of her guilt by falling deep into fantasy (and maybe madness) once again.

And so we end as we began: the horse and carriage and footmen driving in the countryside, either a new beginning, or an endless loop of a nightmare.