Beverly Cleary, America’s Sage of Childhood

Remembering the Oregon librarian whose books—including the Ramona Quimby stories—took middle-class suburban children seriously.

Beverly Cleary, the iconic children’s author, died last Thursday at the age of 104. Like millions of children since the late 1950s, I grew up reading her relatable novels, which always entertained, sometimes enlightened, and never disturbed.

It’s a tattered trope of literary criticism—often a sign of laziness on the part of writers and editors—to say that a midcentury author is “nearly forgotten” or “ready for rediscovery.” Many cultural artifacts from this period are, in fact, forgotten, at least by the younger generations. But despite her earliest work now being seventy years old, Cleary remains at least as beloved today as she was at the heyday of her career. She continued producing children’s novels into the 1990s, and various editions of her books are still in print. After HarperCollins announced the author’s death on Thursday night, my Twitter feed quickly filled with grateful remembrances.

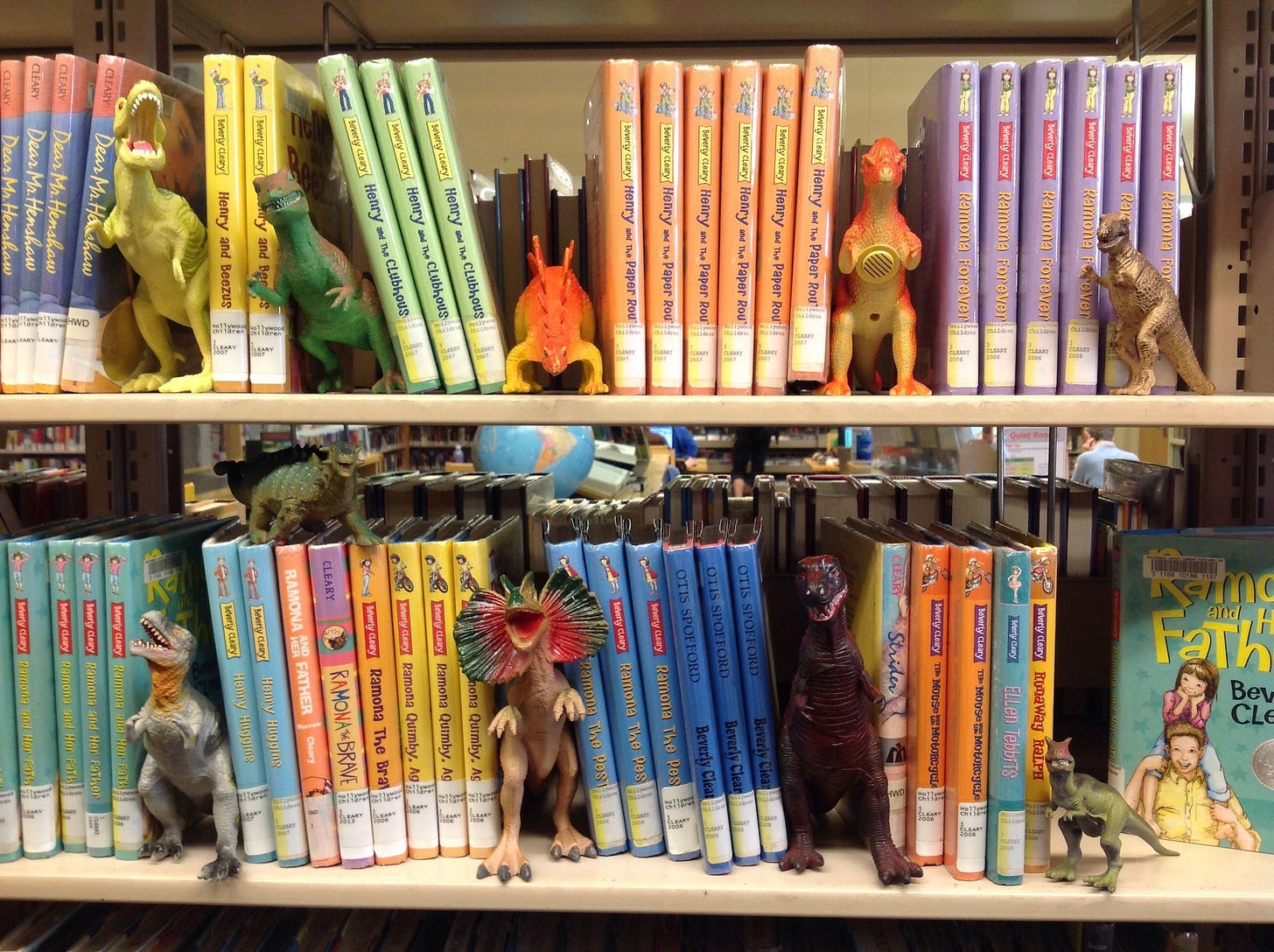

Via the Multnomah County (Oregon) Library (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Grateful for what? Perhaps because her stories felt more like slice-of-life adventures than novels with neat morals and conclusions. Because she fashioned young and teenaged boys and girls into characters with real depth, without falling into the trap of making parents dumb. Because she celebrated, as Rachel Vorona Cote writes at LitHub, girls who are unabashedly “too much”: “Most crucially, Ramona [probably Cleary’s most popular character] is dissatisfied by the template for any childhood that doesn’t accommodate her brash exuberance.” And not only girls; my mother, in fact, compared me to Cleary’s rambunctious Ramona, and I’m sure I recognized a kindred spirit on the page.

For me, who grew up homeschooled, Cleary’s fun, realistic depiction of childhood expanded my world. Perhaps the world Cleary depicted was sanitized; there was very little in the way of divorce, real interpersonal acrimony, heartbreak, illness, abuse. (She even wrote adaptations of Leave It to Beaver, though, in her words, “I cut out dear old Dad’s philosophizing.”) But I grew up in a stable family not unlike the ones that populated her novels, and I had no need at the age of 7 or 8 to be exposed to life’s unlucky miseries. Cleary didn’t shock, but neither did she moralize.

Cleary’s joyful yet serious focus on childhood in suburbia gave her books a contemporary feel. Beyond simply taking children and their thoughts seriously, she didn’t write with an overt or obvious purpose. Her books, especially the Ramona titles, are chock-full of vignettes that fundamentally ring true. In a rather famous one, Ramona mistakes the “dawn’s early light” from “The Star-Spangled Banner” for “dawnzer lee light”—and guesses that a “dawnzer” is a lamp which produces a “lee light.” In another, Ramona finds a crate of apples her mother has bought, and takes a single bite out of each one—because the first bite always tastes the best. Like Calvin and Hobbes’s Bill Watterson, Cleary perceptively saw the humor in childhood, but she didn’t manufacture or invent it. She wrote “with the perspective of an adult but enormous empathy for children.”

Perhaps even more importantly, her books were wholesome and earnest, and never evinced any political or ideological agenda. If the idea of treating young girls as protagonists was itself viewed as radical by some, that misjudgment is on them. But if Cleary was motivated by a sort of feminism, it was a feminism without ideology. She is sometimes seen as a less controversial and risqué alternative to Judy Blume, whose contemporaneous children’s novels were more thematic, dealing in particular with puberty and some sexual themes. Even Blume mostly reads as innocent, even quaint today—but like Elvis and his hips, one can understand why she sparked controversy. Cleary rarely did. That she was a librarian from famously liberal Portland, Oregon makes this rather remarkable.

The famous Ramona was not Cleary’s only protagonist. There was Ralph the biker mouse, for example. Socks—which apocryphally provided the name for President Clinton’s cat—featured a married couple with an infant son and the titular cat. The Ribsy/Henry Huggins books were much in the “boy and his dog” tradition, sans the final chapter where a coming of age is symbolized by the beloved dog’s death. (Perhaps Cleary made a conscious decision to forgo such emotional gut-punches, which are pleasantly missing from her children’s oeuvre. Or perhaps such stories logically followed from the privations of pre-war, and especially Depression-era America.) She was prolific, writing forty-odd books—and while some are better than others, she produced a great deal of excellent work.

To read Cleary today is to feel wonder, simplicity, and contentment. In a time when “young adult” novels sport titles like The Bone Witch, and when children’s books feel manufactured and engineered, with every six-month age increment treated like a market segment, Cleary’s body of work has become a relic. It recalls the time when books, like movies and television shows, could appropriately entertain a whole family, without vulgarity or condescension. And it recalls a time when a wonderfully talented yet eminently ordinary librarian could become a literary superstar by chronicling everyday middle-class life.