Calculating the Cost of the Pandemic Shutdowns

Not only did they save lives, they likely helped save the economy, too.

The United States is now more than three months into the pandemic-induced economic shutdowns that have kept people from normal patterns of working, shopping, learning, and playing in public spaces. The process has been bumpy and uneven, with some states and regions remaining in lockdown longer, while others moved to reopen not long after they closed. The debate over the shutdowns has only grown more divisive and strident as time goes on.

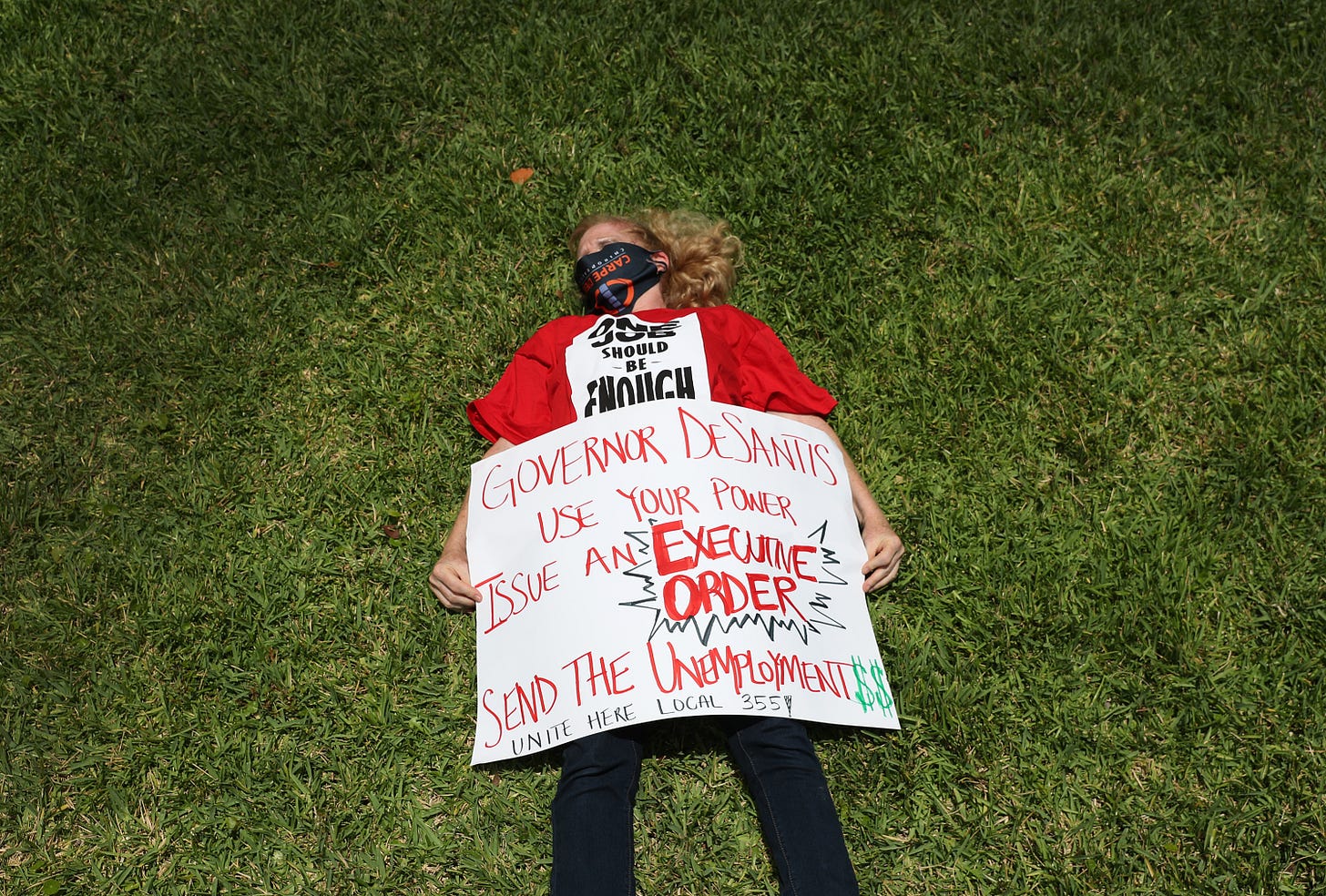

The frustration and angst among Americans is warranted. Tens of millions have lost their jobs, some temporarily and others permanently. To add insult to injury, the unemployment system has struggled to keep up with claims from families that desperately need help. The government has spent trillions of dollars on relief packages, and the lack of transparency in federal spending has sometimes obscured where and how that money has helped to limit the economic damage. To say the least, we remain in very rough economic waters.

Given the circumstances and uncertainty of the moment, it is natural to wonder how things might have turned out had our elected officials navigated conditions differently.

Although it may not feel or look like it, there are many ways in which the shutdowns, as deeply unpleasant as they have been, have made things better for us all. Evidence suggests there will be short- and long-term benefits from these restrictions that will ultimately outweigh the costs of the recession for states and localities that stay the course.

Before looking at that evidence, it is essential to emphasize three caveats. First, we are still in the midst of an evolving situation, one that could change radically. The pandemic could become much more severe or much less; the economy could become much weaker or stronger; other factors could powerfully affect either, rendering any existing models or projections irrelevant.

Second, the data we have at our disposal today is incomplete and preliminary. Even figures that would seem to be fairly straightforward to calculate, like the national death toll and unemployment rate, are subject to dispute and revision. It will take years, and the combined efforts of epidemiologists, economists, demographers, historians, and other experts and scholars, before we have reliable and widely agreed upon data regarding most of the economic and public health aspects of the pandemic crisis.

Third, there are human factors related to the pandemic and the shutdowns that we may be able to quantify only partially, and only after years have passed—if at all. What effects will many months of missed schooling and socialization have on children, especially young children? What will be the long-term effects of this season of loneliness and social distancing on people’s wellbeing? It can be difficult to capture these and other such questions via meaningful metrics, but that doesn’t make them less vitally important.

Having stated those caveats about the limitations of our knowledge, let’s see what we can say about the costs and benefits of the shutdowns.

According to an estimate by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, the economic shutdowns during the first wave of COVID-19 cost the U.S. economy between $225 and $464 billion, calculated in terms of lost production. These losses have forced many companies to lay workers off and many stores have gone out of business. It may take years to recoup the production and income the country gave up to try to limit the spread of COVID-19.

At the same time, the Mercatus study also found that government-imposed shutdowns also prevented between 930,000 and 1.1 million deaths—and that doesn’t take into account actions by individuals and organizations that preceded the closures. That’s millions of people who have been spared the trauma and grief of a tragic and painful death of a loved one. These spared lives also have economic value. After assessing each human life with a value-of-production approach, as well as factoring in potential income losses for patients who would have been temporarily ill with coronavirus, the total amount saved comes out to between $440 billion and over $1 trillion. Taken together, the report estimates the economic benefit from the shutdowns to be anywhere from a net of roughly zero to a net positive of $800 billion.

And there are other benefits when we consider more recent developments in the approaches taken by different regions of the country. States in the Northeast shut down early, dramatically, and for an extended period of time. These states are now engaged in a gradual reopening process, and their rates of infection are either holding steady or declining. By contrast, many states in the South and West imposed less stringent restrictions and opened sooner. The rapidly rising number of infections and the higher positive testing percentages in these states are forcing businesses and government to backtrack or delay their reopenings, prolonging, albeit justifiably, the damage to their economies. These start-and-stop openings are also likely to exact an even higher toll on businesses, especially in the service and retail sector, operating on narrow margins with fewer resources to pay for repeated openings and closings. As difficult as the shutdowns are, strict social distancing and curtailment of certain modes of economic activity are the economy’s best chance to thrive until we have reliable vaccines or medicines.

The choice between saving the economy and saving human lives was, and still is, a false one. In a global pandemic that has affected economic activity the world over, severe economic pain was inevitable, government shutdown or not. Voluntary actions by businesses, schools, and individuals began shutting the economy down before the government got involved. The public’s determination to avoid disease made a recessionary downturn unavoidable. This determination will also be critical to getting the economy back on its feet as soon as possible.