Can Christian Compassion Influence How We Treat Migrants?

Finding a holistic solution to the humanitarian crisis at the border is going to take more than an enforcement-deterrence only approach.

The humanitarian migrant crisis at the border that has been building for months reached a staggering new juncture with reports of inhumane conditions for children in detention and the drowning deaths of Salvadoran migrants Oscar Alberto Martinez Ramirez and his daughter Valeria in the Rio Grande as they tried to get to the United States to declare asylum.

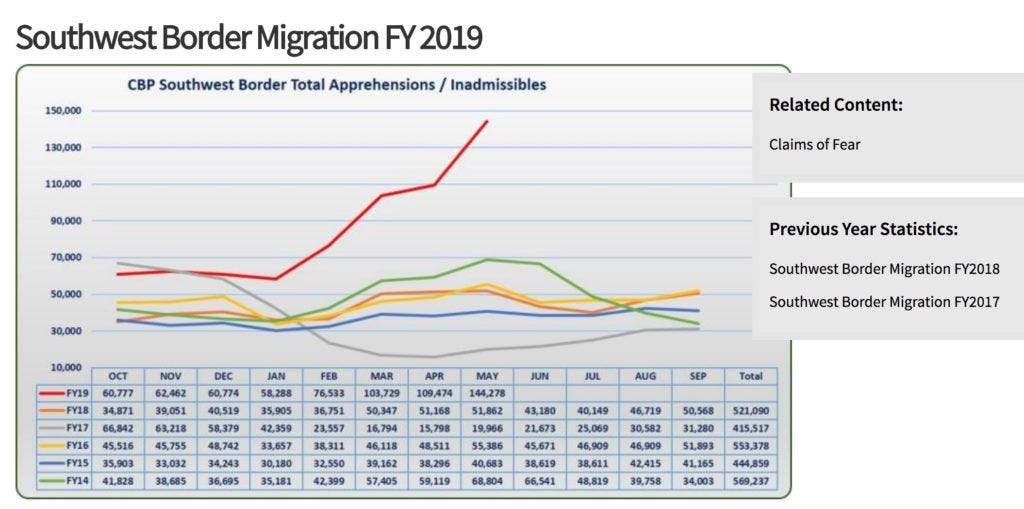

There have been 133,000 other migrants apprehended at the border in May, including 96,000 members of family units and unaccompanied minors. The number of border apprehensions for the fiscal year through May were nearly 600,000, including more than 330,000 members of family units. We are on pace for the highest numbers of apprehended migrants at the border in over a decade.

Facing this crisis, the clear goal of the Trump administration is to keep migrants from coming to America. But is the harsh rhetoric, zero tolerance, metering of asylum seekers at border crossings, child and family detention, the expansion of detention facilities, cutting off foreign aid to Central American countries, and family separation policies actually achieving that goal? The more we detain and the harsher we are, still more people come—if they can get here by any means possible.

It is clear, the enforcement-deterrence only approach employed by the Trump administration has not worked on its own. While new measures employed by Mexico at its southern and northern borders go into effect and initial reports are that the numbers of asylum-seeking migrants declined in June, we must step back and look at the bigger picture of why migrants are coming here.

The situation in Central America where migrants are coming from is horrendous enough for people to leave all they have known and risk their lives to come to America. I’ve been to the border three times in the past 10 months and have heard from migrants and aid workers in churches from El Paso to San Diego. The stories of desperation involve people fleeing violence, corruption, extreme poverty, rape, murder of family members, extortion from criminal gangs, and abductions. It is understandable why they have fled their homes in search of a better place.

I’ve visited churches in El Paso and Tijuana that have been turned into shelters for migrants, serving hundreds a day as they wait for their chance to apply for asylum or as they’ve been released by ICE to rest and gather themselves together before joining extended family in the United States.

I’ve looked into the eyes of desperate people, of mothers with blank stares holding their children in their arms. The most chilling experience involved walking into a church sanctuary in El Paso that had been converted to a migrant shelter serving people too exhausted to make a sound. They just sat there staring in silence with empty looks on their faces, worn down from a long journey. They had just made it through the border after presenting themselves for asylum.

The situation at the border is not sustainable nor acceptable in regard to the sheer number of migrants coming, the “Remain in Mexico” policy that creates even further desperation as thousands of migrants pile up in border towns, the overcrowding of detention facilities on the U.S. side, the overall treatment of migrants in detention, nor the reported number of children who were sleeping in Border Patrol stations on cold floors without soap, toothbrushes, or proper care. Border Patrol agents are neither equipped nor capable of dealing with this kind of situation. The list of what is not working here goes on and on. We need a better approach, an approach that considers the human dignity of migrants and that also includes compassion as an influence on border policy.

Christians have been speaking out about this and have gotten louder over the past week. Dr. Russell Moore, president of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission (ERLC) of the Southern Baptist Convention tweeted recently that “The reports of the conditions for migrant children at the border should shock all of our consciences. Those created in the image of God should be treated with dignity and compassion, especially those seeking refuge from violence back home. We can do better than this.”

This should be a pretty basic, run of the mill response from a Christian theologian to reports of migrant children sleeping on concrete floors and not being able to bathe for weeks at a time or have their diapers changed. But, in an odd turn of events (or what would have been considered odd just two years ago), Jerry Falwell Jr., president of Liberty University, represented another take on the collision of religion and politics and fired back at Dr. Moore over what he perceived to be a swipe at President Trump. He tweeted, “Who are you @drmoore? Have you ever made a payroll? Have you ever built an organization of any type from scratch? What gives you authority to speak on any issue? I’m being serious. You’re nothing but an employee- a bureaucrat.”

Falwell’s perspective is ridiculous. He himself has inherited his wealth and position from his own father as have many others. But, he demonstrates that what cannot be inherited is compassion.

Jesus shows us how to have compassion for others. Matthew 9:35-36 says “And Jesus went throughout all the cities and villages, teaching in their synagogues and proclaiming the gospel of the kingdom and healing every disease and every affliction. When he saw the crowds he had compassion for them, because they were harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd.” When Jesus saw the crowds, instead of judging them or rejecting them or ascribing base motives to them, he was moved with compassion for them. Jesus says something similar in Luke 10:33 when he says that the Good Samaritan had “compassion” on the man beaten and lying on the side of the road by tangibly caring for him. This kind of compassion doesn’t come automatically to individuals, nor is it inherited by a nation from past generations. It has to be cultivated through the development of character and through proximity and engagement with people in need. And that isn’t always an easy process.

One possible way to maintain balance, compassion, and better care for children with security and orderly processing of asylum seekers is to restart Alternatives to Detention (ATDs) through the Family Case Management Program (FCMP) that attaches caseworkers with migrant children and families. This is cheaper than detention and had a high success rate. DHS’s Office of Inspector General reported that “according to ICE, overall program compliance for all five regions is an average of 99 percent for ICE check-ins and appointments, as well as 100 percent attendance at court hearings.” Unfortunately, the Trump administration shut this program down in June 2017.

If the enforcement-deterrence only approach isn’t working to bring order out of chaos, perhaps we should also consider how compassion and upholding human dignity as values in the midst of this humanitarian disaster can help us find better solutions. Just over two weeks ago, the Evangelical Immigration Table, a coalition of 10 evangelical organizations and denominations including Russell Moore’s ERLC, released a letter calling upon the president and Congress to holistically address the humanitarian concerns of children and families in detention as they seek to secure the border and restore order out of chaos.

As a Christian, I do not believe that compassion is contradictory to order, well being, and proper governance. If it were, Jesus would not have called us all to have compassion and love for our neighbor in need, including the sojourner.

Compassion is not inherited, either in individuals nor in nations. It must be cultivated and that cultivation often happens in trial when we are tested. America is being tested right now. How will we respond to the migrants coming to us desperate for help and refuge? How will we respond to the sight of Oscar and Valeria drowning and being found face down on the banks of Rio Grande in each other’s arms? How will we, as a nation, respond to overcrowded detention centers filled with scared and desperate children and to a growing number of thousands of migrants amassing in cities on the Mexico side of the border waiting for their asylum claims to be heard? This is not just a security discussion. This is a humanitarian crisis where compassion for people is also needed to help us work through the proper solutions. We need to do the hard work of figuring out how to treat migrants with compassion and like people in need rather than as threats, nuisances, or drains on our country. Maybe then we will discover the best way forward.