Can Republican Virtue Save Democracy?

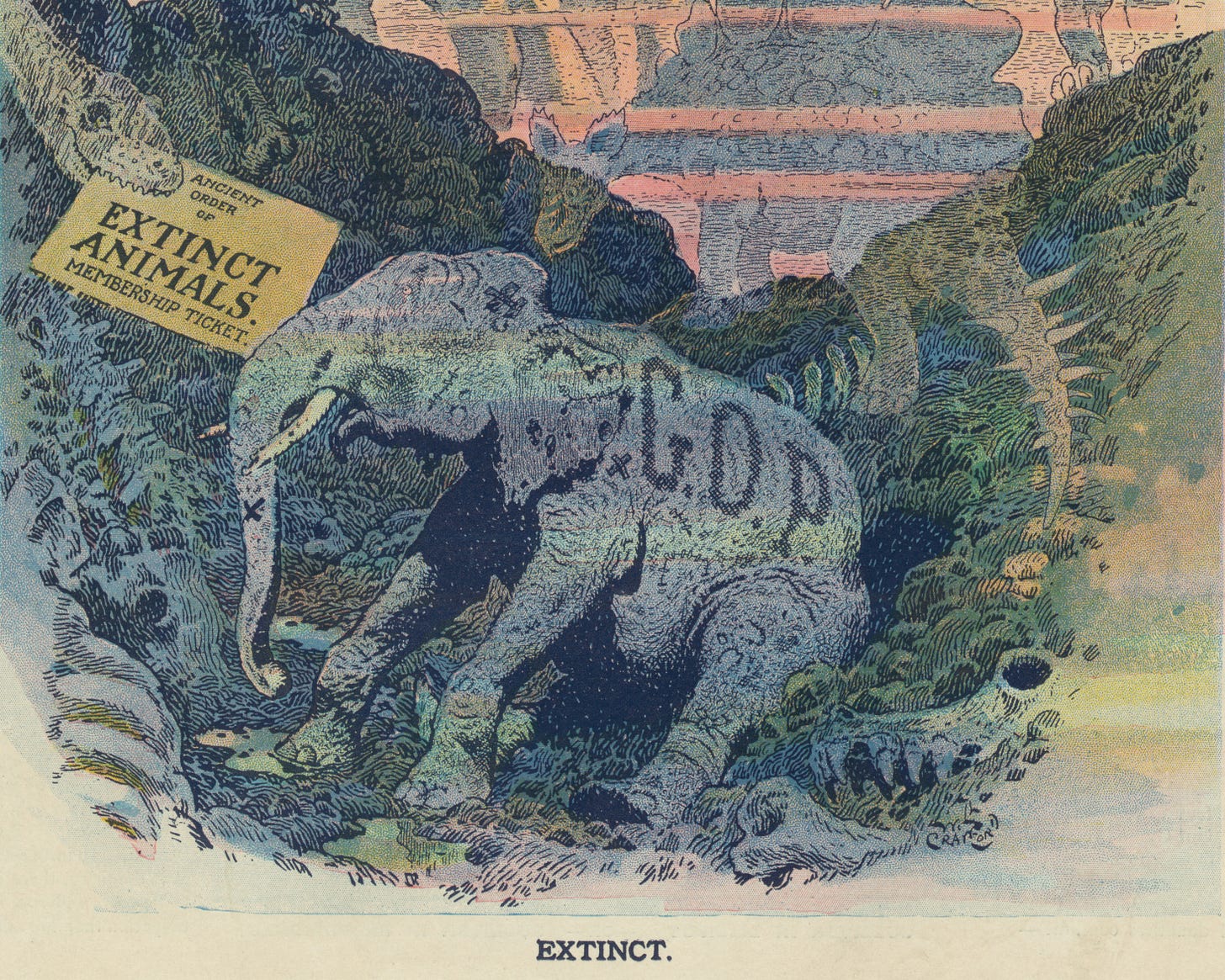

American democracy is ailing. Small-r republicanism can help revitalize it.

Though democracy has survived in America for more than 240 years, the rise of populist nationalism here, and its increasing synchronization with populist nationalism in Europe, are worrying evidence of democracy’s vulnerability.

It is easy to find culprits for the rise of populist nationalism. Commentators regularly blame globalization and its unfair distribution of benefits, the increasing distance between a small wealthy elite (think Davos man) and middle-class wage earners, illegal immigration and mass migrations, stagnating of opportunity, alienation from the political class, and much else.

It is not so easy, though, to find suggestions of how to reverse these trends and save democracy.

Here the longstanding confusion over whether America is a democracy, a republic, or both, may offer a path. The Founders proclaimed the new nation a republic, but one with elements of democratic government. It is timely to consider whether the former may save the latter.

Whereas democracies focus on equality and justice, the characteristics of republics include popular sovereignty, a sense of the common good, civic virtue, and resistance to corruption. Let us discuss each of these in turn.

First, popular sovereignty. We tend to assume that the center of political power in the United States is Washington, D.C. But in a republic, power belongs to the people, who are sovereign. Yes, we do select representatives to promote and protect our individual and national interests. But they are ultimately accountable to us, the sovereigns.

Around the world, we have seen in recent years a shift away from popular sovereignty toward autocracy, in which executive and legislative power, and sometimes even judicial power, are brought together into the hands of a single individual. Even here at home, over the last three years we have seen worrying steps toward autocratic style, rhetoric, and action.

Next, our sense of the common good. “It is not the pursuit of individual good but of the common good that makes cities great,” Machiavelli writes in his Discourses on Livy, “and it is beyond doubt that the common good is never considered except in republics.”

Our sense of the common good wanes in ordinary times and waxes when we are threatened from abroad or when our economy becomes depressed at home. To put it another way, the common good is obvious when survival is at stake, but in ordinary circumstances most of us have to be reminded about the very long list of institutions that belong to all of us and that keep our country interconnected—our intricate national security systems, interstate transportation systems, public lands and resources, research laboratories, monetary protections, and on and on.

Civic virtue is the duty we all owe our republic to participate in self-government at all levels and to cultivate the habits of behavior necessary for self-government: civility, engagement, mutual respect, integrity, reason, and maturity. Without such participation—without making use of the right to govern ourselves—all other rights are jeopardized. Unfortunately, civic virtue is perennially moribund.

Finally, resistance to corruption. Corruption, understood as placing special or personal interests ahead of the common good, has been the plague of republics throughout history. Our national, state, and local governments are hotbeds of special pleadings and thus corrupt by this classical definition, which is much broader than bribery.

These four characteristics of republics are all linked: Our failure to exercise our sovereign powers through protection of the common good and through the exercise of civic virtue weakens our resistance to corruption. And they all are rooted in an understanding of people not as autonomous individuals but rather as citizens. As Rousseau observed, “There can be no patriotism without liberty, no liberty without virtue, no virtue without citizens.”

How, then, can resuscitating the republican characteristics of our political life help shore up American democracy? Here are three suggestions.

First, much public discontent and suppressed anger is due to the perception—and too often the reality—that laws are passed and high court rulings enacted to legitimize undemocratic systems at war with our republic’s principles and values. The Supreme Court decision in the Citizens United case, giving corporations First Amendment speech protection (namely, unlimited spending related to elections) stands as the worst example of this trend.

One partial remedy for this problem is sunlight: Policymakers, candidates for office, and citizens should demand much more transparency and openness. It would go far to restore integrity to all levels of government in our republic, and thereby to protect our democracy.

Second, we should greatly increase our support for public and private projects focused on civic engagement and civic virtue. Consider the religious and private humanitarian efforts underway at the southern border to aid separated families and children in need. Or Share Our Strength, which provides tens of millions of meals to hungry children. Or AmeriCorps, which has for years established urban projects for young people who receive education financing in return. Or First Book, which provides books to children whose homes have no books.

Private philanthropy can never totally replace a democratic government committed to equality and justice for all. And government programs can never totally replace the local wisdom and innovation of robust private charity and activism. But together, they can do much to repair the damage done to our democracy by the selfish and unconcerned.

Finally, imagine a reformation in which citizens began to exercise their sovereignty on a daily basis by demanding regular accounts of the health of the commonwealth, all those things we hold together and in trust for future generations. Imagine those same citizens taking an evening off from television to attend a city council or county commission meeting, a school board meeting, a parent-teacher evening, or a candidate town-hall speech, or listening to a podcast on an issue of the day.

This kind of awakening of republican citizenship would start to drive the lobbyists and money changers from our halls of government. Broad-based citizen participation would do much to restrain the single-issue politics now dominating the public square and would greatly restore the standard of the national interest to legislative debate.

There is precedent for this kind of public mobilization. The various post-WWII political movements—in support of civil rights, equality for women, nuclear arms control, and action on environmental and climate issues—were instances of citizens taking charge of the public agenda. They are proof of popular sovereignty in action.

Democracies protect rights. Republics promote duties. In a word, we must protect our rights by performance of our duties.

Restoration of the republican ideal will by no means cure all the ills afflicting American democracy. Our country’s geographic and demographic sweep, its massive internal mobility, and its fragmentation of authority from the national to the city level, all mitigate against the establishment of the stable, interconnected, mutually dependent polis identified with republics throughout the ages. But applying republican principles to democracy’s discontents offers the best hope of revitalizing and restoring our politics.

“I believe that republicanism has the historical and moral resources to revive or indeed engender civic enthusiasm, without a revelation of faith and without a dogmatic belief in history or in a leader,” wrote political philosopher Maurizio Viroli in his 1999 book Republicanism. “Either we shall find a way to reinforce republican politics and culture, or we shall have to resign ourselves to living in nations whose governments are controlled by the cunning and the arrogant.”

The choice is clear: Revitalize our democracy by restoring the principles of our republic. Or, by continuing to walk away from republicanism, risk losing our democracy, too.