Can the Republican Party Be Saved? Should It?

The GOP has been the home of right-of-center political views for more than half a century, espousing limited-government, anti-communist, internationalist, fiscally balanced, economically liberal ideologies—though its politicians sometimes failed to live up to those ideas.

The past decade or so has seen a shift in the party’s core ideologies. Republicans increasingly favor government intervention in social and economic matters, reject internationalism in favor of either unilateralism or isolationism, and unapologetically run up large deficits. Most disturbing, some of them embrace what they call “national populism”—and what can more accurately be described as “white culturalism.” This view holds that people of certain cultural and/or racial identities and traditions have a special claim on the nation’s rights and privileges, and have been underserved by recent American public policy.

It is tempting to blame this transformation on Donald Trump, in part because the new GOP views cohere poorly with the party’s previous ideologies. However, Trump could not have become leader of the Republican party and president of the United States if the new views hadn’t already found a home in some quarters of the party and the broader U.S. electorate.

Hence the dilemma of the anti-Trumpist right (ATR, from here on out): Is Trumpism now the party’s enduring dogma, or can the GOP exorcise these new views and return to (and perhaps more faithfully follow) the ideologies of its previous era? The answer to this question entails nothing less than whether ATR members will have a home in the Republican party going forward or are now political refugees.

Many on the ATR believe the previous Republicanism can be restored. This belief appears to be the product of hope, not evidence. The ATR would be better served to attempt to create a new party than to try to return the GOP to its previous state. Such a party could be a vital fortress against both Trumpism and the far-left-wing progressivism that is rising in the Democratic party.

The American Political Space

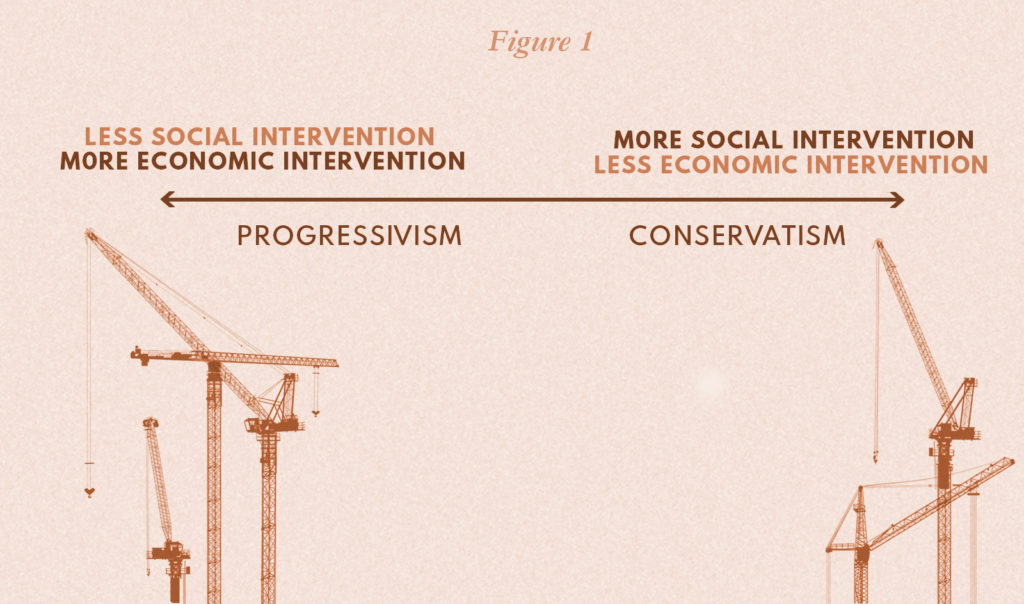

Conventional wisdom arranges American political ideologies along a single dimension, as pictured in Figure 1. The right side is typically labeled “Conservativism” and the left side “Liberalism” or (more accurately and contemporarily) “Progressivism.” This division entails that the primary dividing issue in American politics is where government should intervene more heavily in human life: the social realm, concerning morality and religion; or the economic realm, concerning consumer and producer choices. Conservatives are said to favor broad government intervention in social issues but limited intervention in economic issues, while progressives favor strong government intervention in economic issues but limited intervention in social issues.

There are significant problems with this idea, despite its widespread use in American politics. One obvious problem is that some ideologies map to different places in the unidimensional space than where those ideologies’ own proponents — and their allies and opponents — claim. Many environmentalists, for instance, have moral motivations for their views, which would put them on the conservative side of the divide. Yet environmentalists usually ally with progressives and clash with conservatives.

This leads to a deeper problem with the unidimensional view: It is unlikely that “social intervention versus economic intervention” is the fundamental divide in American politics. There are many Americans who believe government should intervene heavily in both realms, and many others who believe government should be less involved in both.

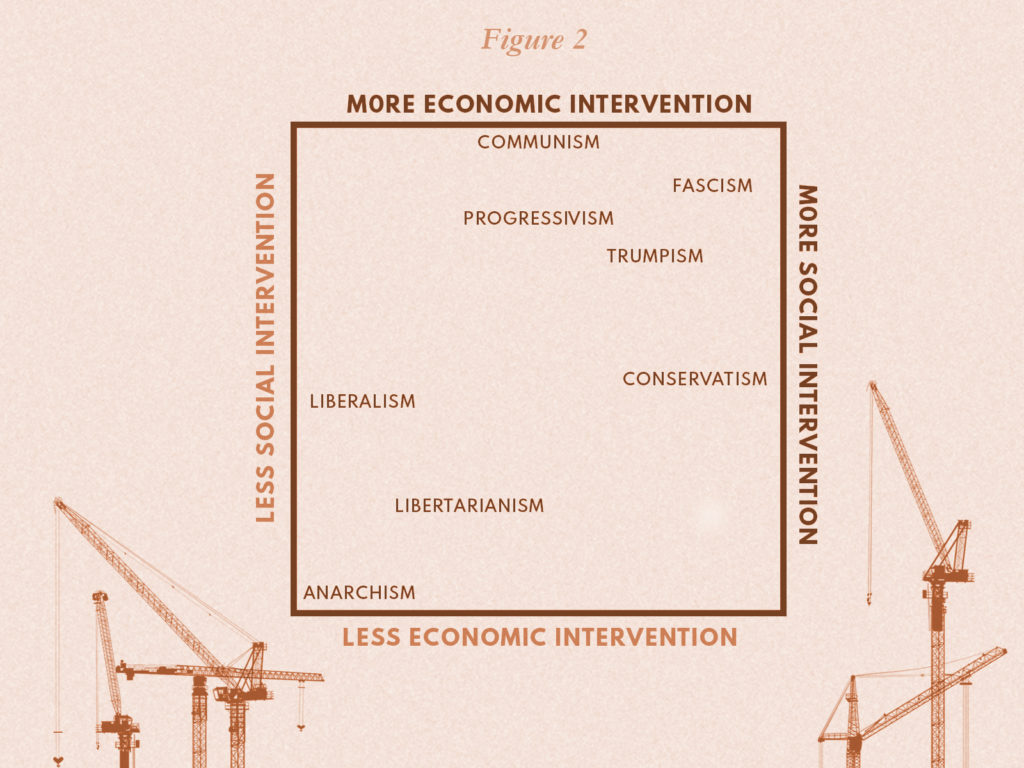

Some commentators have suggested thinking of American political ideologies in two-dimensional space. Attitudes toward social and economic intervention can be placed on opposing axes, with each axis ranging from less to more. Figure 2 depicts this and maps some American political ideologies in this space.

This idea better locates some American ideologies, but others still end up in odd places. For instance, Trumpism, fascism, communism, and progressivism all map fairly closely together, yet members of those groups are unlikely to see all of the others as fellow-travelers.

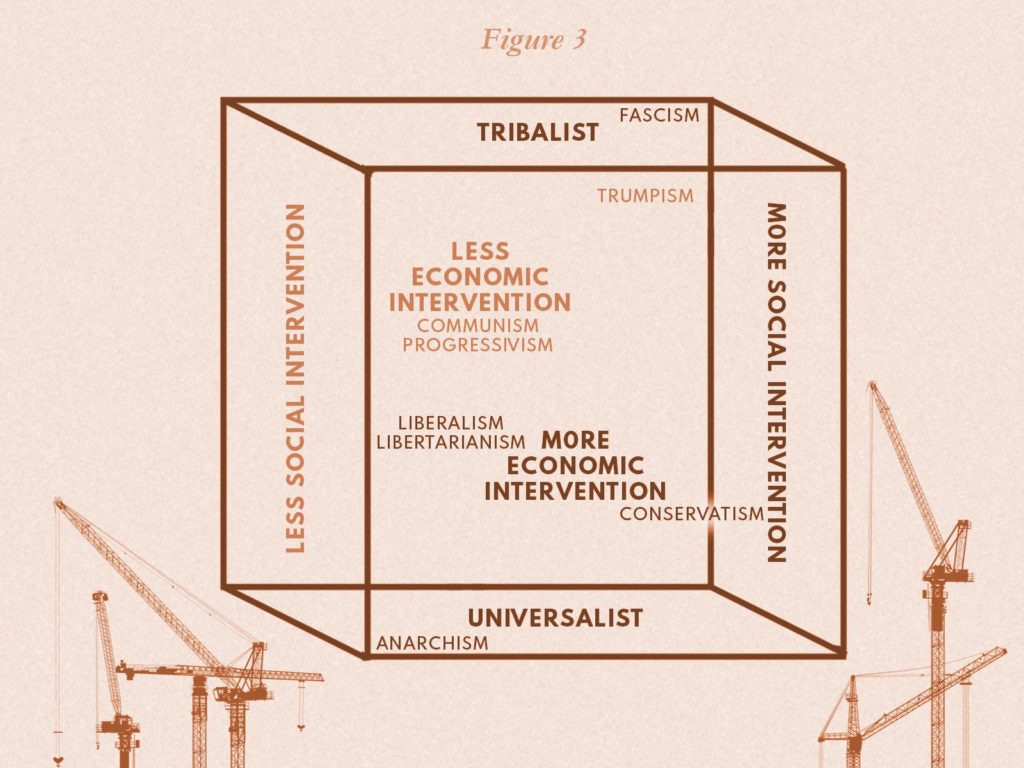

To more accurately locate some groups, we can add more axes. One ideological axis has grown in importance in the last decade or so, especially in the 2016 presidential election: group identity. Many Americans increasingly identify as members of a specific cultural, class, and/or racial group that they believe should have special political rights and privileges. This axis would range from “Tribalist” on one end, indicating a strong belief that a group should have special privileges, to “Universalist” on the other, indicating a belief that rights and privileges should be held by (or denied to) all persons equally, regardless of culture, class, or race. Figure 3 adds this Tribalist/Universalist dimension to the previous two-dimensional figure.

This mapping is still imperfect (for reasons beyond the problem of rendering a three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional page). Progressivism, for instance, could be mapped in either the Tribalist or Universalist region, depending on whether the mapper is thinking of the original progressive movement (which was white culturalist) or its contemporary namesake. Likewise, libertarians can be mapped in either space, as some libertarians have strong universalist beliefs while others (sadly) have more tribalist views. However, this figure nicely maps the Trumpists, who have a very strong tribalist view that is separate from their views on social and economic matters.

In 2016, the Trump electoral coalition succeeded because it attracted a number of tribalist voters from such groups as Christian social conservatives, rurals, blue-collar households, and cultural Southerners. Trump’s appeal to these voters improved Republicans’ chances of electoral victory because some of these tribalists—especially blue-collar households—previously tended to vote for Democrats or were disengaged from the electoral process.

In appealing to tribalist voters, Trump did repulse some members of the previous Republican coalition—those aligned with the ATR being the most obvious. But he did not repulse enough of them to offset the tribalist gains. Hence the Trump coalition proved (barely) adequate to capture the Electoral College and the presidency.

The question for those on the anti-Trumpist right is whether the tribalists are now a permanent, politically powerful part of the Republican coalition—and arguably, under Trump, the controlling power. If the tribalists are an enduring Republican power player, then the ATR must either accept being part of such a party or divorce themselves from the GOP. In weighing this second possibility, they should consider whether a successful new political party can be cobbled together in the ideological space incorporating universalism, libertarianism, centrism, and conservatism—and perhaps some other parts of the three-dimensional ideological space.

Room for a Successful Party?

A recent analysis from the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group seems to discourage the idea that a new political party could be successful. Drutman, Galston, and Lindberg do find that an overwhelming majority of Americans (68 percent of those surveyed) say the country’s current two major parties do an inadequate job of representing the American people and that a third party is needed. However, the researchers note, there is little agreement over what ideologies a new party should embrace. About a third of the disaffected voters (25 percent of those surveyed overall) want a more centrist party between the Democrats and Republicans, while nearly a quarter of the disaffected (16 percent overall) want a party that is to the right of the Republicans and nearly a fifth of the disaffected (12 percent overall) want a party to the left of the Democrats. This division seems incapable of yielding a unified, successful political party.

However, there are reasons to be more optimistic about the prospects of an anti-Trumpist party.

The first is that Trump, himself, successfully created a de facto new party. He displaced a number of the Republican party’s core ideologies, replacing them with tribalism and in essence creating a new party that propelled him to the White House. If he could do this, then others may be able to craft a successful party by grafting a universalist ideology onto the previous Republican ideologies.

A second reason for optimism is that, according to Drutman, Galston, and Lindberg’s data, party voters—Republicans and Democrats alike—have stronger disagreement with the opposing major party (which they overwhelmingly say “very poorly” represents their views) than they have agreement with their own party (the majority of both Democrats and Republicans say their party only “somewhat” represents their views). An anti-Trumpist party would not be burdened with such sharp disapproval and thus may be able to attract voters throughout the ideological space that the Trumpist GOP is moving away from. More and more of these voters may become available as the Democratic party—undergoing its own ideological turmoil—aligns more closely with its staunchly interventionist progressive wing, contracting in its own ideological space and ostracizing civil libertarians and “Third-Way” or “Clinton” Democrats. Given the nation’s future fiscal challenges, an increasingly pro-interventionist Democratic party will likely be as hard-pressed to attract a majority of voters as a Trumpist Republican party will.

Path to Success

An ATR party could become what political commentator Chris Ladd describes as a “second party.” Despite the rough national balance between Republican-leaning and Democrat-leaning voters, many electoral districts—ranging from localities to whole states—are so dominated by one party that the other is politically insignificant. Yet these districts still have serious disagreements over precisely how much government intervention is acceptable, and in what areas. Those disagreements provide an opportunity for a new party to succeed by being a politically competitive voice of non-extremism. Examples of such success include Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan Jr. and Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker, popular Republicans in heavily “blue” states, as well as U.S. Sen. Joe Manchin, a Democrat in a very “red” state.

An ATR party could also become a major national party by supplanting an imploding Trump Republican party. Handicapped by the ideological conflicts between its growing tribalism and its previous laissez-faire philosophy, and hostile toward increasingly important demographics of the American electorate, a Trumpist GOP will struggle to continue being the opposing major party to the Democratic party. As Maurice Duverger argued last century, political systems employing single-representative districts will favor a two-party system if the representative is selected by plurality. If a Trumpist GOP can no longer serve as an effective major party, an ATR party can usurp the GOP’s place as the major-party opposition to the Democratic party.

Even if this new party were not to reach such lofty status, it could still play an outsized role in directing national policy. A coalition-building minority can have considerable political power, as demonstrated by now-retired Justice Anthony Kennedy’s effect on judicial decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court. An ATR party that aligns with the GOP on policies that cohere with ATR ideologies, but then aligns with the Democratic party on other issues, could be a controlling force in American politics.

Why Not Restore the GOP?

ATR members may nonetheless be inclined to try to rehabilitate the Republican party. This is understandable. As a major party, the GOP has strong legal advantages at all political levels throughout the United States, and it would take considerable effort for a new party to attain a similar position. The Republican Party also has physical assets, intellectual property, financial resources, and a large and effective network of leaders, operatives, donors and supporters. And it has a rich legacy that many voters cherish — Abraham Lincoln, Calvin Coolidge, Dwight Eisenhower, Ronald Reagan — and would find painful to abandon.

However, that legacy now includes the party’s turn to white culturalism and the elevation of the divisive Donald Trump to party leader and U.S. president, as well as the sycophantic adoption of Trumpism by most GOP leaders. Voters will remember this for decades to come, tainting future GOP candidates regardless of their views on Trumpism. This comes at a time when non–white culturalist voters, including college-educated women and Hispanics, are increasingly powerful constituencies. It is an open question whether the American electorate will ever again give Republican candidates policy-making majorities at the national level.

Moreover, it’s unclear whether control of the party can be wrested away from the Trumpists. Chants of “Build the wall,” “Lock her up,” and “Enemies of the people” are now standards on the Republican stump, along with vows to “Stand with President Trump.” In adopting Trumpism, Republican candidates and party officials are only following the will of a controlling bloc of party voters. And that bloc is growing inside the GOP; a 2017 poll of Republicans found that more of them consider themselves to be Trump supporters than Republican party supporters.

ATR members reject the fundamental tenets of Trumpism. White cultural tribalism—especially the outright racism embraced by some Trump supporters—is morally repulsive. Protectionism is foolish economic policy that especially harms middle- and lower-class American households. Fiscally irresponsible policies result in wasteful uses of public resources and heighten national economic risk. Populism is an appeal to the “lowest common denominator” of voters, and populist candidates exhibit declining moral and intellectual standards as they endeavor to maintain their appeal. And Trump’s pugilistic political style—now aped by other Republicans—is ineffective in forming majority coalitions necessary to implement policy change and gain the general support of the populace—as evidenced by the Trump administration’s failure to implement many of its policy goals. In attempting to rehabilitate the Republican party, ATR members would be trying to defeat what is now the party’s dominant ideology and manner, in order to then form common cause with the proponents of that ideology and manner.

This strategy has a very low probability of success. Since Trump became the party’s standard-bearer, he and his supporters have pushed out the few party leaders who criticized him and his agenda, replacing them with Trump loyalists. Even if he loses the 2020 general election, his surrogates will continue to hold party power for years to come. The first legitimate opportunity to begin removing them will not come until after 2024—and then only if the party chooses a nominee who is a serious departure from Trump. Thus, in the best case, Trumpism will continue to dominate Republican party leadership through 2025.

Moreover, the gains from this strategy would be meager even if it proves successful. Gaining control of the GOP would mean the ATR has captured a disgraced, morally compromised, broadly disliked, and distrusted party. It’s unlikely such a party could produce governing majorities nationally anytime soon. Benefit–cost considerations recommend the ATR try a different strategy.

The GOP's Due Should Not Be the ATR's Due

In his second inaugural address, the greatest Republican president, speaking of the offense of slavery, described the terrible cost of the Civil War “as the woe due to those by whom this offense came.” The GOP now has woe due for the offense of Donald Trump. That debt will include forever being remembered as the political vehicle of white culturalism.

ATR members who want to rehabilitate the party are volunteering to pay an outsized portion of that woe due, even though they are not the ones by whom the Trump offense came. Their payment is neither necessary nor helpful to the nation, which needs a successful and respectable right-of-center political party to combat the dangers of both Trumpism and progressivism. Instead of attempting to rehabilitate the GOP, ATR members would better serve the nation and respect themselves by attempting to create a new party that respects the ideas of the previous Republicanism and promotes those ideas to the American electorate.