Candidate Kanye’s Call for a More Godly America

Among the precedents: Joseph Smith’s ill-fated 1844 campaign.

Last week, rapper and producer-turned-preacher Kanye West released his first presidential campaign ad. Full of typical but still striking imagery ranging from farmers to firefighters, the language of West’s ad is saturated with theological appeals and religious conviction. West, shown in three-quarters profile from a low angle, looking away from the camera, summons the viewer: “To contemplate our future, to live up to our dream, we must have vision.”

“We as a people will revive our nation’s commitment to faith, to what our Constitution calls ‘the free exercise of religion,’ including, of course, prayer,” West says. “Through prayer, faith can be restored.” Cut to shots of nature, families at prayer, smiling children at play, and so on. He concludes by saying that “by turning to faith, we will be the kind of nation, the kind of people God intends us to be.”

At first glance, West’s ad might look more like a call for a religious revival than a message from an aspirant for the highest office in the land. But Ye is certainly not the first unlikely presidential contender to try and infuse presidential politics with talk of the Kingdom of God.

When it comes to the history of American religious politics, most voters, pundits, and scholars have expressed interest (or concern) in those spiritual leaders directly involved in party politics. Some of these individuals have been household names, such as Billy Graham, who aided Richard Nixon in his pursuit of the presidency. Televangelists Jerry Falwell and James Robison were both key figures in the Reagan Revolution. Historian John Fea has dubbed President Donald Trump’s religious cronies—including Jerry Falwell Jr., Robert Jeffress, and Paula White—“the court evangelicals.” And Republicans haven’t cornered the market on religious politics—as witness the rise of Jimmy Carter to the presidency or Pete Buttigieg’s constant appeals to his faith.

Of course, religious-political alliances have not always produced the happiest of relationships, with religious activists often complaining about how little they have received in return for their support of the candidate in question. Many religious Americans of have felt used, ignored, and mistreated by the reigning political parties. This has sometimes led religiously inclined voters to seek out alternative options. For example, with the Iraq War in mind, in 2008 progressive evangelicals Shane Claiborne and Chris Haw promoted the idea of “Jesus for President.” Against the Trumpian transformation of the GOP and its abandonment of Christian values, numerous devout candidates have stepped forward, such as evangelical Don Blankenship of the Constitution Party as well as the independent and Christian Reformed Church pastor (and Navajo citizen) Mark Charles.

Now enter Kanye West.

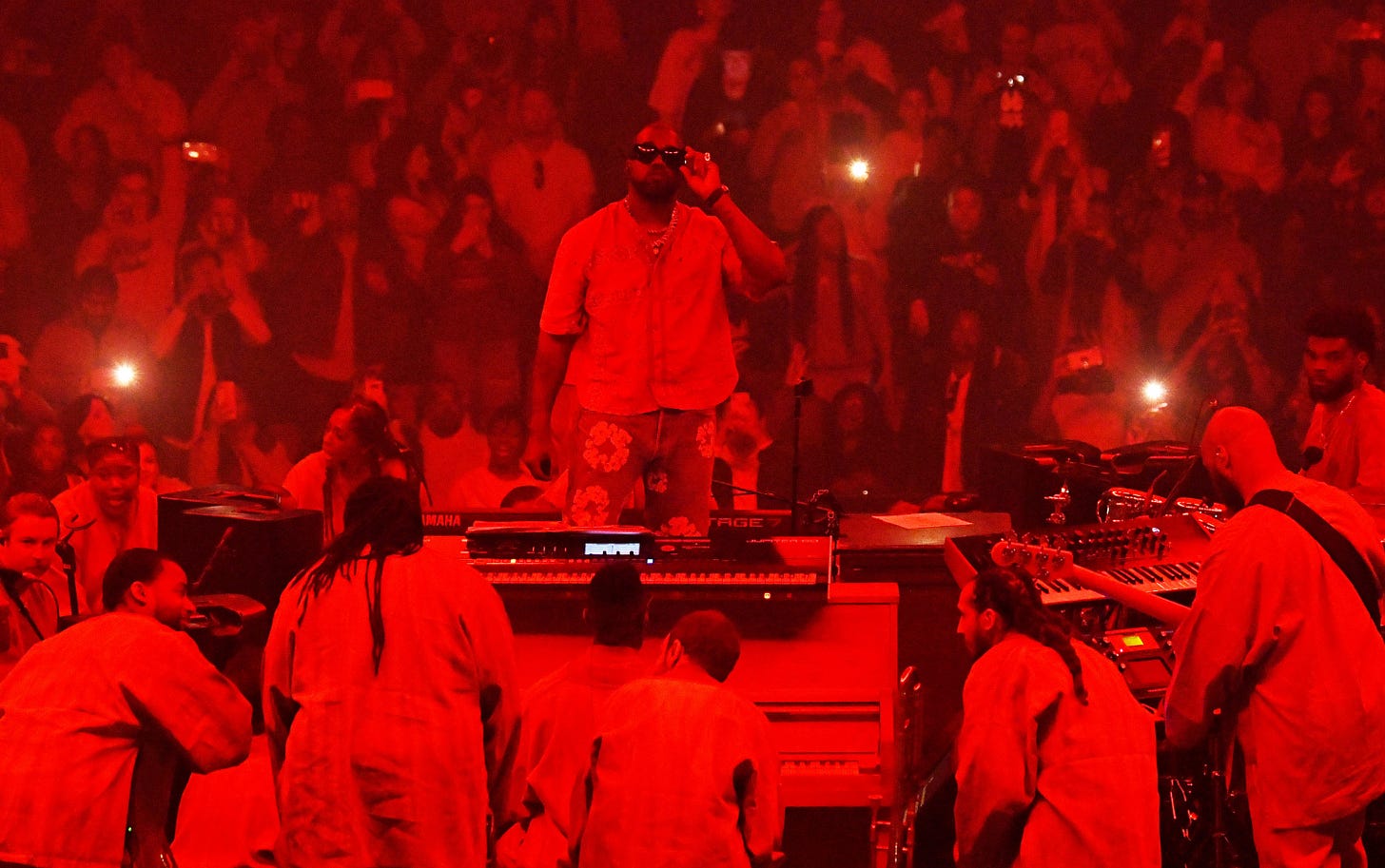

Since the election of Donald Trump, West has been a lightning rod for controversy. Some of West’s most infamous moments include describing slavery as a “choice” on TMZ, defending conservative provocateur Candace Owens (and then distancing himself from her), as well as a bizarre meeting with President Trump in the Oval Office while sporting a red MAGA cap. It was also around this time, at least as far as was publicly visible, that West began his spiritual reformation—a process that led to the release of his ninth studio album, Jesus is King, and his Sunday Service concerts. The album sparked a wide range of reactions from music critics, secular fans, and Christians, with many drawing parallels between West’s religious turn and Bob Dylan’s Christian period in the late 1970s.

After a few years of teasing a presidential run, West declared the start of his campaign on Twitter on July 4, 2020. He is on the ballot in only a dozen states. The campaign has not been without controversy, as when West strangely criticized abolitionist Harriet Tubman at a South Carolina rally.

Religious themes and theological wrestling have long been prominent in West’s music. Many of his greatest hits—going back to “Jesus Walks” in 2004—have dealt with the struggles of living a Christian life while in an industry that applauds lavish lifestyles, easy sex, and criminal activity. He has sometimes presented himself as a musical deity—as in “I am a God” on his 2013 album Yeezus (a play on the name Jesus)—a figure equally venerated by his fans and reviled by his detractors. As Hillary Crosley Coker puts it in her video essay studying the religiosity of West’s discography, Kanye is “a man of God with a God complex.”

While many view West’s presidential gambit as a joke, a publicity stunt, an elaborate marketing scheme, or a manifestation of his mental-health problems, it can also be seen as standing within a tradition of religious-political protest. The nineteenth century saw a whole host of religious movements with a range of political aims. Some—such as Robert Matthews’s Kingdom in New York, the perfectionist Oneida Community, and the Shakers—attempted to opt out of the American political system. Modern manifestations can be seen in the People’s Temple (which led to the Jonestown mass murder), the Branch Davidian movement (which led to the Waco siege), and Buddhafield (now famous thanks to Netflix’s documentary Holy Hell). Many of these groups eschewed voting or otherwise participating in U.S. politics (unless it benefited them with more religious liberty and political autonomy). Sometimes, though, they ran their own candidates for office, or otherwise participated in elective politics, inside and outside the Democratic and Republican parties. In 1984, for example, Ma Prem Kavido of the Rajneesh movement was one vote away from becoming an alternate delegate to the 1984 Republican National Convention.

But perhaps the most interesting case of religious political protest can be seen in the 1844 presidential bid of Mormon founder and prophet Joseph Smith Jr.

After numerous forays into politics, Smith and the Latter-day Saints had isolated and infuriated both the Democratic and the Whig parties in Illinois. With the dawning of the 1844 presidential election, Smith contacted the five men whom he assumed would be the front runners: John C. Calhoun, Lewis Cass, Richard Mentor Johnson, Henry Clay, and Martin Van Buren. While Johnson and Van Buren did not respond, Calhoun, Cass, and Clay replied—all three stating that while they more or less sympathized with the Mormons’ position, they could not offer any special privileges or protections to Smith and his church. In the face of little support, Smith and his closest followers met in his office on January 29, 1844 and decided the prophet should be the Mormons’ candidate.

The platform of Smith’s “Reform Party” called for a restoration of America’s greatness and appealed to Christian virtues. Much of his vision relied on melding together the sovereignty of God and the people: He proposed the United States become a “Theo-democracy” in which “God and the people hold the power to conduct the affairs of men in righteousness.” Presenting himself as above party politics, Smith declared: “We have had democratic presidents: whig presidents; a pseudo democratic whig president; and now it is time to have a president of the United States.” His platform also included a call to end slavery with a plan to compensate slaveholders for their human property. Other plans Smith had in mind included reducing the pay of congressmen, forming a national bank, and annexing Oregon and Texas.

About four hundred missionaries were sent out across the United States to stump for Smith’s candidacy. The campaign did not get very far, as Smith was arrested and, on June 27, 1844, assassinated by an angry mob.

Like Joseph Smith’s bid for the presidency, Kanye West’s run will end in failure (although presumably less gruesomely). Obviously, West’s campaign is a very different enterprise, given his immense celebrity and the question of whether his candidacy is in earnest or a cynical ploy—but West’s ad shows that he, like Smith before him, wants to call upon Americans to restore a lost godly republic. West surely won’t be the last outsider presidential candidate to make that plea.