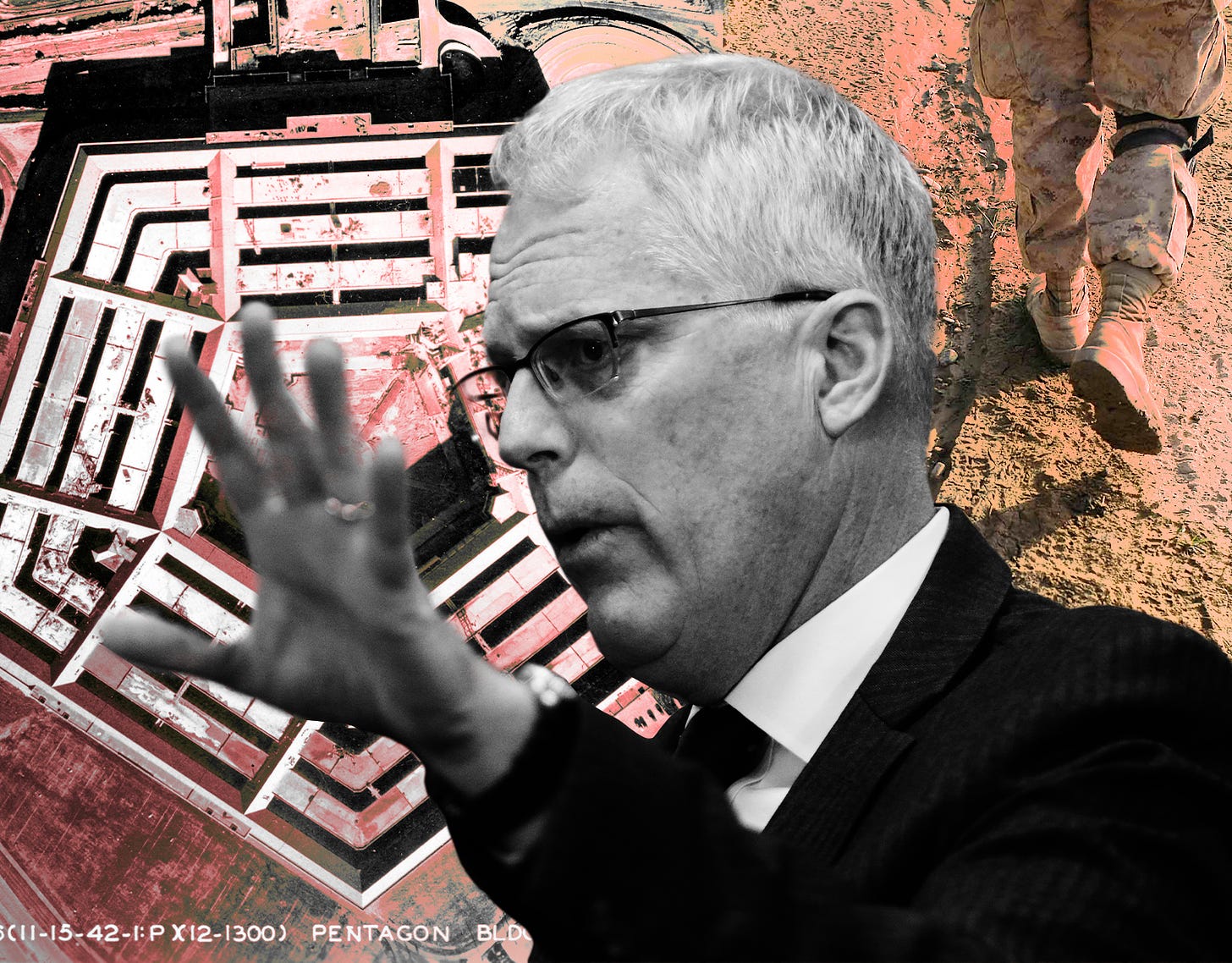

Chris Miller, the MAGA SecDef, Explains His Anger

In a memoir he recounts his military career and his eventful short tenure as Trump’s last Pentagon chief—including his bitterness about Jan. 6th.

Former Acting Secretary of Defense Chris Miller can list plenty of reasons to justify his reluctance to send troops to secure the Capitol on January 6, 2021—but, as he writes in his new book, Soldier Secretary, he is also self-aware enough to know when he is being “generally a dick.”

Which happens a lot.

Reading this memoir makes it easy to see why President Trump appointed him. Miller is a pissed-off MAGA-friendly former Green Beret eager to give the finger to the establishment, which he does with remarkable candor and callousness. So much so that he remains, even now, unapologetically unbothered by the danger that elected officials were in on January 6th.

In the opening pages of his memoir, he describes then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi as being “in a state of total nuclear meltdown” and other congressional leaders “hyperventilating” in their calls for help that day. He is smug, smirking over how the speaker decried the use of National Guard troops to put down Black Lives Matters protests, but “as soon as it was her ass on the line, Pelosi had been miraculously born again as a passionate, if less than altruistic, champion of law and order.”

And that’s just the beginning. Miller’s book brims with disdain for congressional leaders. Examples:

“I never could have imagined anything like this—getting reamed out by a histrionic Nancy Pelosi and Mitch McConnell as they implored me to send troops to forcibly expel a rowdy band of MAGA supporters, infiltrated by a handful of provocateurs, who were traipsing through the halls of the Capitol, taking selfies, and generally making a mockery of the entire institution.”

“I have never seen anyone—not even the greenest, pimple-faced 19-year-old Army private—panic like our nation’s elder statesmen did on January 6 and in the months that followed.”

“Do I blame a bunch of geriatrics for acting like a bunch of geriatrics? Of course not. But do I judge them for it? You’re damned right I do. Most of all, I resent that we are ruled by a bunch of geriatrics that ruthlessly and selfishly maintain their hold on power and refuse to develop the next generation of leaders.”

All of that was just in the introduction, which partially ends on this note: “Other than my family and handful of friends, I don’t give two shits about what anybody thinks of me.”

Okay then.

But before we get to January 6th and the rest of Miller’s tumultuous but very brief tenure as acting secretary of defense, it’s worth learning what’s behind all the hostility and why he went so MAGA in the first place.

Christopher C. Miller is, by any measure, one tough motherfucker.

He joined the armed forces through ROTC, became a Special Forces officer, and was one of the first soldiers to hit the sand in Afghanistan after 9/11, and again in Iraq in 2003, leading the Green Berets on missions in both countries. Miller, who toiled under exhausting and harrowing conditions, didn’t get one break until June 2003, after the successful invasion of Iraq. Then, at home, on leave and alone with his thoughts, he said that he became “horrified” with what he had done.

“I couldn’t escape the conclusion that I had been an active participant in an unjust war,” he said. “We invaded a sovereign nation, killed and maimed a lot of Iraqis, and lost some of the greatest American patriots to ever live—all for a goddamned lie. . . . The further we got from the war zone, the more my stress turned into burning white-hot anger.”

His descriptions of war are spare but vivid. He tells of the human remains of a friendly fire disaster he came upon soon upon arrival: “raw hamburger meat scattered all around me”; he calls a successful building clearing operation a “well-orchestrated ballet of death and destruction to which professional soldiers always aspire”; and the recalls how the “incinerated remains of an Iraqi soldier” were “the most stunning and vibrant purple color I had ever seen.”

During his tours of duty, he embraced unconventional warfare tactics and became disillusioned about the effectiveness of expensive military infrastructure and equipment.

He freely bashes Congress for “abrogating its constitutional duties regarding the declaring, funding, and overseeing [of] our nation’s wars. . . . The guardrails established by the founders had been crumpled like those run over by our tanks on the Thunder Run to Baghdad. And nobody cared.”

He resents the “techno-miliary evangelists” who give the impression to soldiers that they will be able to “apply extraordinary violence humanely and with supreme discretion.” Miller blames “an inexperienced corps of journalists, media personalities, and elected officials—the vast majority of whom haven’t been personally involved in the dirty, barbaric fights that are the essence of warfare” for amplifying such ideas along with the “the think tank crowd” that “doesn’t have any skin in the game.”

To that end, the subtitle of Miller’s book is “Warnings from the Battlefield & Pentagon about America’s Most Dangerous Enemies.” Because he believes America’s real enemies are not on foreign soil but teeming in Washington and the news media. You might be tempted to believe that the sentiment Miller expressed above is meant as hyperbole, but he returns to it again and again in his book.

After completing his final combat tour in 2007, Miller held several defense-related positions, including a three-month fellowship at the CIA and in 2010, he was made the Pentagon’s top uniformed official for Irregular Warfare policy. In a chapter titled “Deadliest Enemy,” Miller said his “opponents” inside the Pentagon “were far more dangerous” than Iraqi insurgents “in terms of the damage they could do to the United States.”

I was overrun by legions of low-talent, low-energy obstructionists who were nevertheless quite formidable. Like the enemies I faced in Afghanistan, the DOD bureaucratic blob knew the terrain, they were deeply entrenched, and they had been defending their fiefdoms from invaders like me since time immemorial. . . .

Civilian control of the military had been inculcated in me since my first high school civics class, and it always sounded logical to me. Now, seeing it up close for the first time made me nauseous. While he did soften and regained some respect for civilian control of the military—the civilian control he himself would eventually lead—Miller continued to think of the bureaucratic factions who disagreed with him as foes. His perceived enemies were those who rejected the more flexible, nimble, cheap, and human-focused paradigm of Irregular Warfare in favor of what he calls the “Traditional Warfare” or “Big War” paradigm (think WWII-style military-to-military fighting). Miller suggests cutting the U.S. military budget in half because “the way you defeat terrorism is not by spending ungodly sums on ships and jets, but by strictly enforcing our border—which by, and large, our political elite refuse to do.” He doesn’t believe our foreign enemies will attack America head-on, preferring instead to “use the tools of disinformation, economics, subversion, resistance, and cyberwar” for which we are not well-equipped to fight.

Miller couldn’t make any transformational changes at the Pentagon, but after a few years figured out how to become bureaucratically “dangerous” and protect Irregular Warfare assets from the chopping block. He didn’t like the work, though. “I realized that if I kept swimming in The Swamp, I would eventually sink into its mucky depths and be absorbed. It was time to go,” Miller said.

He retired in 2014 after 27 years of service.

Retirement by itself did not make Miller any less angry. Looking to address his intense feelings and unpack “unpleasant memories” he stored “on a shelf deep in the recesses of my psyche,” he decided to train for a sub-three-hour marathon. Miller characterizes the long runs his training regimen required as “personal therapy,” and he used them to reflect on his experiences. During this period, he said,

I had come to believe that many of the psychological wounds of war are caused by moral guilt brought on when an individual violates their belief structure or sense of self. I’m not talking about the act of killing other fighters—that’s part of the job, and military personnel are trained and toughened to deal with it. But the military doesn’t prepare its people for wounding or killing a civilian or a child. If only the war my generation fought, and the motives behind it, were as clean and comprehensible as the popular media portrayed it.

I also had to deal with the simmering sense of betrayal that every veteran today must feel—the recognition that so many sacrifices were ultimately made in the service of a lie, as in Iraq, or to further a delusion, as in the neoconservatives’ utopian fantasy of a democratic Middle East. It still makes my blood boil, and it probably will until the day I die. He accomplished his goal of a sub-three-hour marathon, but “found I still hadn’t quite run the war out of my system, so I kept at it.” He signed up to run the JFK 50 Mile race in November 2017. Despite suffering an ankle injury going downhill during one of the race’s early portions on the Appalachian Trail, he finished second in his age group.

It wasn’t long after that that the Trump administration called him up. Miller found new ways to channel his anger.

Trump appointed Miller to a high-level National Security Council post in 2018, with counterterrorism and transnational threats as his portfolio. In that position, he reported to National Security Advisor John Bolton, whom Miller now describes as being “perennially in favor of sending American troops to die in whatever godforsaken war is currently being discussed on cable news.” By 2020, Miller was the director of the interagency National Counterterrorism Center.

Unlike Bolton and other high-ranking Trump officials, Miller agreed with Trump about ending the war in Afghanistan. He explained why and how the war could be brought to a close “on our terms” in a September 2020 Washington Post op-ed. Miller considers Defense Secretary Mark Esper’s reluctance to embrace ending the war to be the main reason for Esper’s ouster a few days after the 2020 election, which precipitated Miller’s ascension to the top Pentagon job. (Esper has provided his own perspective in various forums.)

Although Miller admits he fell “ass-backward into becoming the leader of the largest, most powerful organization in the history of the world,” he claims he wasn’t intimidated. He was eager to put his new influence to use and bring troops home from Afghanistan, Iraq, and Somalia. “This was personal for me,” he writes.

The goals he set for his brief tenure were modest: “no new wars, no military coups, and no troops in the streets deployed against American citizens.” The last point was a throwback to an event much on the minds of administration officials in the days following the 2020 election: the militarized clearing-out of Lafayette Square to provide Trump with a photo op in front of St. John’s Church the previous June.

“Even in the circus atmosphere of the Trump era, I assumed these final goals would be the easiest to achieve,” Miller said. “I had less than three months until the inauguration of Joe Biden on January 20. What could possibly go wrong?”

Miller’s wife was never a Trump supporter and apparently thought he was an “idiot” for accepting the job of acting defense secretary. The day the mob began to gather outside the Capitol, Miller writes, “I was starting to wonder if she was right.”

What Miller says in the book about January 6th is consistent with his testimony to Congress: He consulted with various legal authorities ahead of the protests. There was general agreement that the National Guard would have a low profile because of the concerns about the Guard’s June deployment to Lafayette Square. Some administration officials, Miller included, worried that Trump might invoke the Insurrection Act; Miller received an assurance from White House aide John McEntee that Trump would not do this—although, McEntee added, the president did have the ability. Miller took McEntee at his word; he also believed that, as acting defense secretary, he had all the authority he needed to make his preparations for that day, and therefore he did not need to speak to Trump at all. Trump did make an offhand remark about needing “10,000 troops” in D.C. to protect demonstrators on January 6th, but Miller didn’t take this seriously as an order.

While Miller’s particular judgments, as revealed in these details, may invite disagreement, it’s important to note that his story hasn’t changed. His book and interviews fill in the picture of the thinking behind his decisions. One of the book’s achievements is to make it feel as though Miller is really offering that glimpse into his mind, repellant as it sometimes is, instead of a dull recitation of Trumpist talking points in a committee-workshopped frame.

Miller accuses the media of “selling the idea” that the “U.S. military was a threat to the republic and a pawn in a secret conspiracy by President Trump to stay in power.” As he has done before, he blasts the January 3, 2021 Washington Post op-ed written by ten former secretaries of defense, who in his view, “feign[ed] concern that we would ignore our oaths of allegiance to the Constitution and become Trump’s shock troops.”

Last week, in an interview on Morning Joe, Miller defended himself against the shock-troop charge, claiming he was never asked to do anything extraconstitutional and would have resigned if he had been.

He then defended on separation-of-powers grounds his January 6th decision about deploying the National Guard:

I represented the executive branch, the military. You do not go to Capitol Hill with the military unless you are invited by congressional leadership. If you do anything different, that’s called a military coup, and I was really, really concerned about that. If I would have put additional troops up on Capitol Hill that morning, I think you guys would have been probably losing your minds about . . . a military coup going on, and I wasn’t going to be part of that.

The military, he maintained, should never be used for domestic law enforcement unless civil order has completely broken down—especially in a highly polarized environment where any action could risk appearing to commit the military to one side or another. “That’s what we have cops for,” he said. “People don’t join the military to fight their own citizens.” His anxieties about this were so pronounced that he developed a concern that “the opposition that day was setting up for a Boston Massacre moment,” as though Trump’s political enemies were trying to bait him into killing them with American soldiers.

“That was my assessment of the intelligence, which was pretty weak,” he then admitted.

In spite of his public profile being almost wholly shaped by his time in the Trump administration, Miller insists he is strictly apolitical; he writes that he was only tangentially aware of “bizarre” comments from people like retired General Mike Flynn urging Trump to use the military to overturn the results of the 2020 election. Despite Miller’s vaunted intelligence training and distinguished military career, he would have us believe in his essential naïveté at key moments—as when he blithely took on Kash Patel, a certified kook, as his chief of staff. (Patel’s illustrated book for children, The Plot Against the King, offers a fictionalized account of Trump’s travails set in a fantasy universe. His next book, out this June, could perhaps be described in the same way.)

On Morning Joe last week, Miller was quick to say “I’m not an election denier.” He’s just happy to promote his book in appearances with some of the biggest election deniers in the country, as when he came on Steve Bannon’s War Room podcast. And given how unsparing he is with criticism, it’s notable that he remains incredibly tolerant of Trump.

Consider the strange story he tells about the October 2019 operation to “capture or kill this piece of shit” ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. This is the anecdote in which First Lady Melania Trump suddenly appears in the Situation Room. Then-Secretary of Defense Mark Esper gave up his chair for her, and she took the seat beside the president. Trump introduced her to people around the room as though they would not have known who she was otherwise. Trump then asked that the First Lady be briefed as to what was unfolding.

Miller wondered how it would play in the press if word got out she was in the room during this highly sensitive operation. “Not my problem, I figured. After all, it was her house.” With this very cool, very glib expression, he signals that he was just along for the crazy Trump ride, serious issues pertaining to security clearance notwithstanding.

So she stayed. Someone asked what would happen if al-Baghdadi used a suicide vest. Deputy National Security Advisor Matthew Pottinger wryly explained that “his head will pop off like a champagne cork.” Melania “looked up in horror”—at which point, Miller writes, “I couldn’t take it anymore and burst out laughing.”

The macabre joke was accurate to what happened during the raid. A combat dog led the way into the building, but at that point, the feed reverted to an exterior shot, and those present had to tensely wait for updates in lieu of live footage. Unseen, the special ops team engaged in a “‘no quarters’ fight to the death,” and in the end, al-Baghdadi used the vest to blow himself up while holding his two children. His head reportedly did what Pottinger said it would.

After the mission concluded, Melania “took over” and suggested that Trump focus on the dog used in the raid during his speech about the operation, because “everyone loves dogs.” Trump did exactly that.

Trump also told the public about how al-Baghdadi whimpered in his final moments. Miller claims he doesn’t remember this detail, but he went along with it anyway. The imagined whimpering was just part of Trump’s masterful strategy of psychological warfare, and the ease with which Trump used it attests to his“supremely confident, relaxed, and in control” manner as commander-in-chief.

One can only imagine how Trump’s supporters would react if Jill and Joe Biden similarly tag-teamed in the Situation Room during a crucial special ops mission before spinning the gruesome affair as taking place in the Homeward Bound cinematic universe. Woof.

Miller’s book is a remarkable piece of agitprop. Whether he admits it or not, he is a Trump man. His embrace of the MAGA mindset is most apparent on the pages where he pushes back against narratives about the “insurrection.”

“Yes, the riot at the Capitol on January 6 was stupid and criminal and an absolute disgrace,” he writes. “But it was far from anything resembling an ‘insurrection’ or, as the Democrat slogan repeated ad nauseam suggests, ‘an attack on democracy.’”

Miller then recites the core tenets of the America First agenda, such as it is, with more clarity than Trump ever did himself:

The actual attack on democracy is what has been happening in the halls of the very same building for years or even decades, perpetuated by elected leaders of both parties.

They led us into one pointless war after another, costing us thousands of American lives and trillions of dollars in wealth. They funded the rise of China through trade giveaways, destroying our middle class and creating the monster that now looms over the free world. They opened our borders to an endless wave of crime and drugs that kills more than 100,000 Americans annually. They squandered the strong and proud America they inherited and left our nation weaker and more divided than we have ever been before. What’s remarkable is that Miller still considers himself an apolitical actor. How can that be? Easy: He sees these matters not as conflicts between political parties but rather as us versus them, just like on the battlefield. And he’s Soldier Secretary MAGA.