Classical Music Isn’t Elitist

But some of its woke critics are.

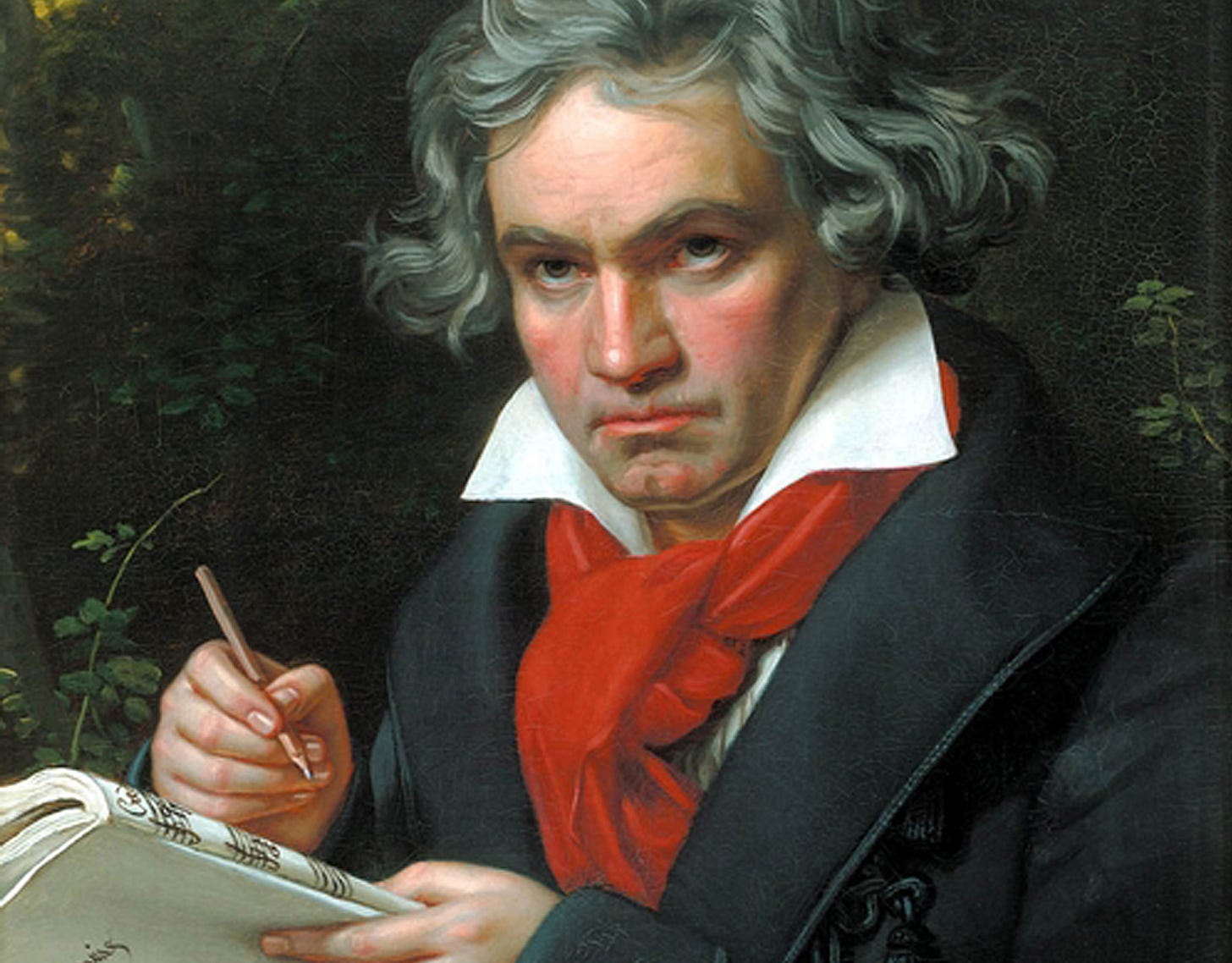

This year has brought a lot of firsts for all of us, but one first I never expected was an all-out attack on Beethoven and his Symphony No. 5, perhaps the most beloved and popular symphonic work of all time. Beyond the specific issues relating to Beethoven, the claims of “elitism” in classical music bother me, partly because it seems odd to be accusing our musical institutions of elitism as they are shuttered and on the brink of collapse, and partly because the claims of elitism simply aren’t true.

“Since its 1808 premiere,” write Nate Sloan and Charlie Harding in Vox, audiences have interpreted the Fifth, with the progression from its ominous opening to the decisive major-key conclusion of its fourth movement, “as a metaphor for Beethoven’s personal resilience in the face of his oncoming deafness,” but “for some in other groups—women, LGBTQ+ people, people of color—Beethoven’s symphony may be predominantly a reminder of classical music’s history of exclusion and elitism.”

They continue:

Today, some aspects of classical culture are still about policing who’s in and who’s out. When you walk into a standard concert hall, there’s an established set of conventions and etiquette (“don’t cough!”; “don’t cheer!”; “dress appropriately!”) that can feel as much about demonstrating belonging as appreciating the music.

But there doesn’t seem to be a single full-time orchestra in the United States that has a dress code for its audience—at least none revealed by some googling. Besides, the mere existence of behavioral norms isn’t an indication of exclusivity or elitism—after all, isn’t it normal to minimize cheering and coughing during movies, too?

Another article, published last weekend in Slate, finds an even sillier sort of evidence for elitism in classical music. According to author Chris White, an assistant professor at UMass Amherst, by referring to certain composers by last name only (Beethoven, Mozart, Bach) while referring to lesser-known composers by first and last name (Florence Price, Clara Schumann, Amy Beach), “music history has created a hierarchical system that, whether or not you find it useful, can now only be seen as outdated and harmful . . . [and] by using everyone’s full names, we can focus more on their music rather than on the past cultural practices that elevated straight white men at the expense of everyone else.”

So, following White’s reasoning, the Vox authors, by referring repeatedly to Beethoven and not even once to Ludwig van Beethoven, are continuing the “unsavory practice of reserving the mononymic surname.” Shame on them, I guess.

But of course that’s just something we do for people who are extremely famous. I don’t need to say Abraham Lincoln or Rafael Nadal Parera or Cherilyn Sarkisian or Kanye Omari West. It’s enough to say Lincoln or Nadal or Cher or Kanye. God forbid I have to write out Johannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart every time I want to mention Mozart.

White’s “fullnaming” idea—an invented word for his invented crusade—seems to belong more in a social studies department at a middle school than a music department at a university. Johann Sebastian Bach versus Bach. We get the point. Doesn’t insisting on full names for everyone seem a little pretentious, annoying, tedious, and dare I say . . . elitist?

I do a lot of talking on behalf of music itself, partially because the field of musicology and music departments in universities and colleges have all but given up on even the pretense of care and love for composers like Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms—the very musicians who, by the beauty and power of their creations, draw kids to music in the first place and continue to move audiences the world over. I also think it’s important to emphasize the universality of this music to puncture the myths about classical music being “elite” or, even stranger, “for the elite.” These myths, I have come to realize, are perpetuated not by curious, less-than-knowledgeable members of the public, but by snide warriors of the politically correct masquerading as hypereducated cognoscenti who possess so much knowledge that they gleefully look to not just restrict our musical diet but to impose theirs on us. Writers like Sloan and Harding might think of themselves as anti-elite and opposed to “gatekeeping,” but in fact they are erecting new gates themselves—as they warn the public of the sinister, narratives of class and race that supposedly run through classical music.

I have been in music long enough (my entire life) to see the power that great music has over people who have no experience with it. Take kids: They know nothing of it, have no background, but fall in love with the sheer sound, and often beg their parents to let them play an instrument. This is what happened to me when I heard the cello for the first time at age three, and it has been my life’s companion.

And the spark of music can work on adults, too. I have done more than my fair share of dragging into the concert hall people who would never ordinarily go, and watching as their lives are changed with one magical experience. I remember summer 2012 in rural Virginia where I served as first cellist for the great, late maestro Lorin Maazel at his Castleton Festival. I had become friends with a local carpenter in his sixties over coffee at the general store. He was afraid to come to a performance of Carmen since he knew nothing about music and felt he wouldn’t “get it.” But I persuaded him to come: I told him that if he didn’t like it, the worst that could happen was that he would have wasted an evening. Far beyond “liking” it, he was reduced to tears. A new passion was born that day for him, and for the next few seasons he came to every single opera, chamber music, and symphony concert until his death this past spring. He always told me how much richer his life was with music and how he wished it had been with him from an earlier age.

Whenever I think of our capacity to love music—even on first hearing—I also remember the time when I was in Qatar a few years ago rehearsing the overture to Wagner’s Tannhaüser. The orchestra had put a clip of the rehearsal online, and I was watching it that evening when a Filipino hotel worker came to offer turndown service. He didn’t speak English well, but we got into conversation. I pointed at the iPad I was using to play the video, and put on the part of the overture where the brasses are playing a huge, noble soaring theme, and the violins are almost fighting back, like an uprising against the brasses—a thrilling, unforgettable passage. The worker told me he’d never had the chance to hear any classical music in his life, yet found himself in tears by the end of the passage. I don’t know if he ever heard a single note of classical music since our meeting. But where the power of music is concerned, that one brief moment speaks for itself.

These are not isolated anecdotes. Great music has the power to captivate anyone who hears it. You don’t need an education or a yacht to qualify as someone who can appreciate it. That might be a hard fact to swallow for ultra-woke, anti-culture crusaders. These joyless ideologues pretend to have the authority to tell millions of unsuspecting listeners, who simply love music for what it is, that no, you are all so poorly educated, how could you so naïvely think it is okay to like Beethoven, and to call him just “Beethoven.” Now there’s some elitism!

For the audience, music is the most democratic of the arts. It isn’t elitist and hasn’t been for decades—thanks to radio and recordings, and especially during this year in which live music barely even exists and everything is being done from our homes and smartphones. What is elitist is pseudo-intellectual glitterati preaching a manufactured moral and political agenda. The idea that classical music is elitist is fake news. Now, let’s go listen to Beethoven’s Fifth.