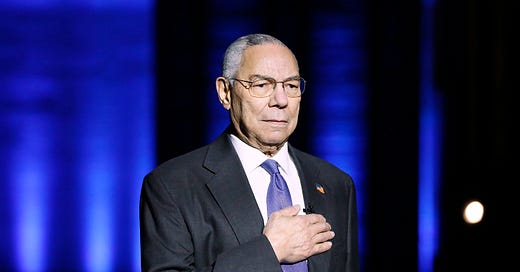

Colin Powell was an impressive man. In private, as in public, he had a presence that was a bit intimidating, a bearing that set him a bit apart from most of the men and women one encounters in important positions in Washington.

Some of this came from his long years of distinguished service in the military. But some of it, too, came from a kind of inner strength and poise too rarely seen in recent years at the higher levels of American life.

It's not that Colin Powell wasn't at times thin-skinned. It's not that he didn't care about his press notices. It's not that he wasn't as capable of bureaucratic maneuvering as the best of them.

But he was more than all of those things, and more than an American success story or a four-star general officer or a well-spoken secretary of State. He was a man, whatever his faults and limitations, whom one felt one should look up to.

And so I did.

I didn't know Colin Powell well. I differed with him on some issues. And my two most memorable encounters with him ended in disappointment on my part. But perhaps that says more about me than about him.

In the fall of 1995 I was part of a small group that encouraged Powell to consider running for the Republican presidential nomination. I had my differences on both domestic and foreign policy with Colin, but I thought he'd have a better chance of defeating Bill Clinton than Bob Dole would have. And I thought a Powell presidency atop a Republican Congress would provide a reasonable combination of moderation and boldness in pursuing a conservative agenda. I wrote a piece in the first issue of The Weekly Standard urging him to run, and then met with him a couple of times to make my case.

Obviously, I failed. He never really confided his reasons for choosing not to try for the presidency—but I suspect he thought he didn’t quite have the mix of qualities necessary for electoral politics in our democracy. He may well have been right. And again, that probably says more about our politics than it does about him.

The second encounter at which I was rebuffed by Colin was, I believe, near the end of 2003 or early in 2004, when he was serving as secretary of State. I requested a meeting with him. This is something I’ve rarely done with people high up in government, since I’ve always figured they could summon me if they ever wanted to hear my thoughts beyond what they could see me saying in public. But in this case I was so concerned—really, appalled—by the management of the war in Iraq, and especially by Secretary of Defense Don Rumseld's refusal to rethink the light-footprint strategy he'd embraced which was leading to civil war and possibly defeat for the U.S.-led coalition, that I requested the meeting, which he took.

And so on the seventh floor of the State Department, I asked Powell to join privately in making the case to the president that John McCain and I and many others were making for more troops—a case that President Bush eventually acted on three years later. Powell was well aware of the arguments. I suspect he partly agreed with them. He listened to me politely, asked a few questions, but gently indicated that he didn't think either Secretary Rumsfeld or President Bush would appreciate his butting in outside his diplomatic lane, and that he would be unlikely to succeed even if he tried. And while he didn’t rule out trying, he didn’t offer much hope. I don’t know if he ever thought it worth trying.

Maybe Powell was right in both cases to reject my over-eager importuning. He certainly saw the realities of the situations in a way that my enthusiasm or alarm may have obscured for me. He was more of a realist than I was. And perhaps his intervention wouldn’t have made a difference in either case.

I'll close with a statement of Colin Powell's that I've always found moving. It was a version of a comment he made many times, I think, but the particular time I recall was in the fraught weeks in the run-up to the Iraq War. Powell spoke at the World Economic Forum on January 26, 2003, and was questioned by a critic of the impending war, George Carey, the former Archbishop of Canterbury. Carey challenged Powell, arguing that the United States was depending too much on "hard power" rather than "soft power."

Here's Secretary of State Powell's response, a fine combination of American realism and idealism in the best traditions of American statesmanship:

The United States believes strongly in what you call soft power, the value of democracy, the value of the free economic system, the value of making sure that each citizen is free and free to pursue their own God-given ambitions and to use the talents that they were given by God. And that is what we say to the rest of the world. . . . There is nothing in American experience or in American political life or in our culture that suggests we want to use hard power. But what we have found over the decades is that unless you do have hard power—and here I think you're referring to military power—then sometimes you are faced with situations that you can't deal with.

I mean, it was not soft power that freed Europe. It was hard power. And what followed immediately after hard power? Did the United States ask for dominion over a single nation in Europe? No. Soft power came in the Marshall Plan. Soft power came with American GIs who put their weapons down once the war was over and helped all those nations rebuild. We did the same thing in Japan.

So our record of living our values and letting our values be an inspiration to others I think is clear. And I don't think I have anything to be ashamed of or apologize for with respect to what America has done for the world.

We have gone forth from our shores repeatedly over the last 100 years—and we’ve done this as recently as the last year in Afghanistan—and put wonderful young men and women at risk, many of whom have lost their lives, and we have asked for nothing except enough ground to bury them in, and otherwise we have returned home to seek our own, you know, to seek our own lives in peace, to live our own lives in peace. But there comes a time when soft power or talking with evil will not work where, unfortunately, hard power is the only thing that works. Colin Powell called his autobiography My American Journey. His life’s journey exemplifies much that has been admirable about the United States of America. His fellow Americans are in his debt, and honor his memory.