Conservatives Should Not Abandon the Free Press

You can’t support the First Amendment for the purposes of protecting speech on campus and campaign spending and then also want to put the Washington Post out of business.

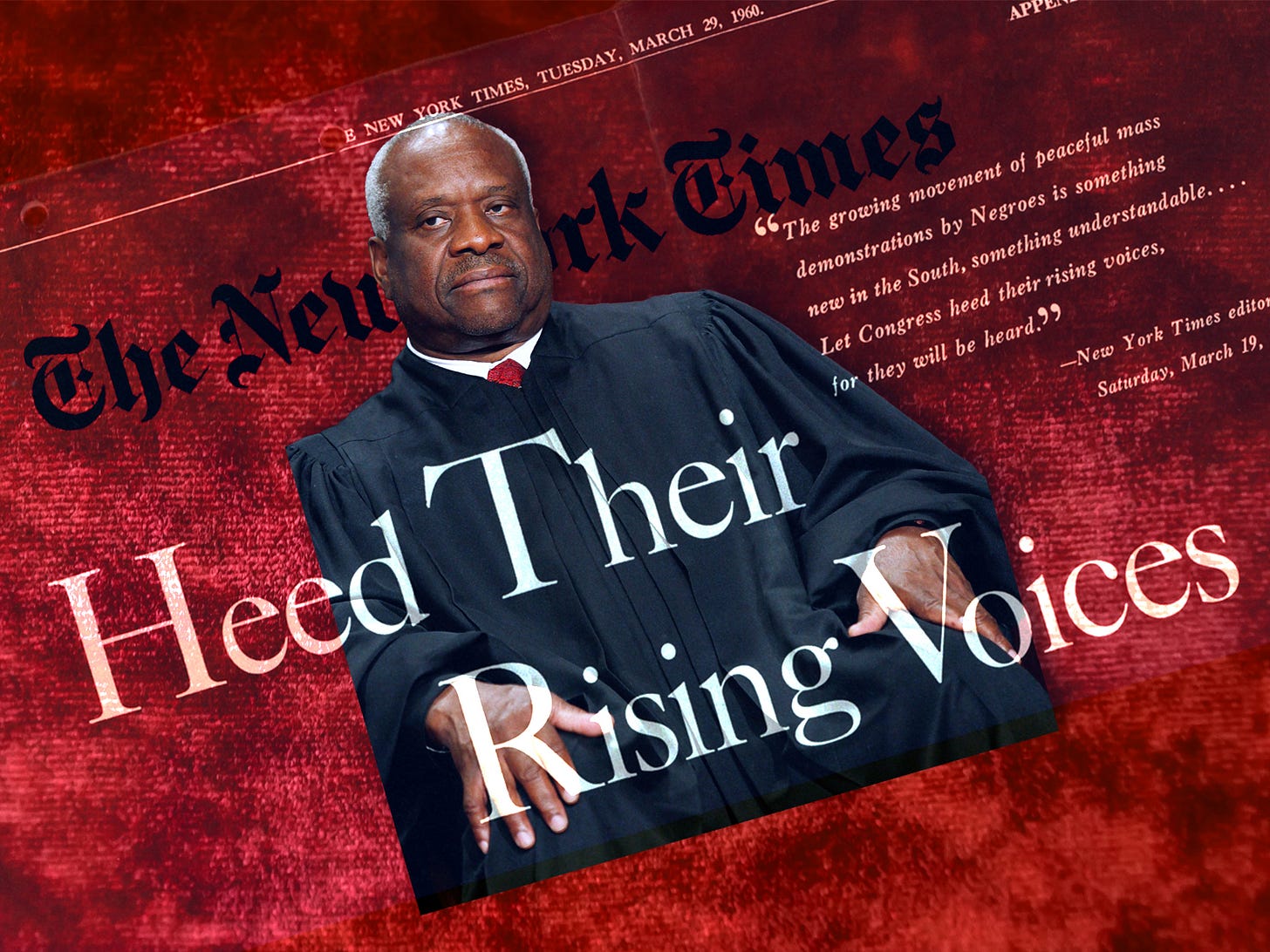

The same day that lawyers for 16-year-old Covington High student Nicholas Sandmann filed a $250 million defamation suit against the Washington Post, Justice Clarence Thomas suggested that the court revisit and overturn the media’s most important protection against such lawsuits.

The two events were coincidental, but nonetheless clarifying; they remind us that the biggest threat to the media is not government censorship but ruinous litigation.

Under the Supreme Court’s 1964 ruling in Times v. Sullivan, public officials must prove that a media outlet acted “with actual malice” in publishing false information. A unanimous court cited America’s “profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open.” Mere errors would not suffice; litigants would have to prove that the media published information “with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard” for the truth.

Justice Hugo Black wrote a concurring opinion joined by Justice William O. Douglas that would have gone even further. “An unconditional right to say what one pleases about public affairs is what I consider to be the minimum guarantee of the First Amendment,” he wrote. “I regret that the Court has stopped short of this holding indispensable to preserve our free press from destruction.”

Despite Black’s disappointment, that ruling has been one of the pillars of press freedom for more than half a century. Times makes it extraordinarily difficult for any public official or political actor to win damages in a court of law. And that, of course, has been a source of frustration for political actors for decades.

On Tuesday, Justice Thomas suggested it be scrapped.

In a brief concurring opinion in a case involving one of Bill Cosby’s accusers (in which he was joined by no other justice), Thomas said “there appears to be little historical evidence suggesting that the New York Times actual-malice rule flows from the original understanding of the First or Fourteenth Amendment.”

Rather, he wrote, the case and the “the court’s decisions extending it were policy-driven decisions masquerading as constitutional law.”

“We did not begin meddling in this area until 1964, nearly 175 years after the First Amendment was ratified,” Justice Thomas wrote. “The states are perfectly capable of striking an acceptable balance between encouraging robust public discourse and providing a meaningful remedy for reputational harm. We should reconsider our jurisprudence in this area.”

At least for the time being, Thomas appears to be an outlier. But it would be a mistake to ignore the threat here.

Given the right’s antipathy for the media, his attack on Times v. Sullivan will get traction in conservative circles, and more quickly than you might think. In fact, it may have been the opening shot in what will be one of the most serious challenges press freedom has faced in decades.

All of this comes at a moment of particular vulnerability for the press, which has seen public trust erode along with its economic viability. Even though Times v. Sullivan is unlikely to be overturned in the foreseeable future, terms like “actual malice,” and “reckless disregard for truth,” are terms of art that rely on a legal and cultural consensus that is being ground down by relentless battering from partisan critics.

President Trump continues to rail against “fake news,” and denounces the press as the “enemy of the people.” Making the matter worse, some members of the media seem intent on proving the president’s point by running shoddy, false, or thinly sources stories that are quickly discredited.

Thomas’s criticism of the court’s precedent also echoes and magnifies Trump’s own hostility to the court’s jurisprudence. (It also reminds us that Thomas’s activist wife is tight with Trump World.)

Trump has denounced the current state of libel law – governed by Times v. Sullivan as “a sham and a disgrace,’ complained that it does not “represent American values or American fairness.” Throughout the 2016 campaign, Trump suggested that he wanted to “open up our libel laws so when they write purposely negative and horrible and false articles, we can sue them and win lots of money.”

He was clear how he might use such a right. “So when The New York Times writes a hit piece which is a total disgrace or when The Washington Post, which is there for other reasons, writes a hit piece, we can sue them and win money instead of having no chance of winning because they’re totally protected,” he said.

Even since his election he has repeated his desire to scrap the media’s protection from libel suits. “We are going to take a strong look at our country’s libel laws, so that when somebody says something that is false and defamatory about someone, that person will have meaningful recourse in our courts,” he declared at one cabinet meeting.

As the Times noted:

Mr. Trump is no stranger to defamation claims, having filed several of them himself, without success. In 2009, a New Jersey judge dismissed a $5 billion suit brought by Mr. Trump against a biographer, Timothy L. O’Brien; Mr. Trump had claimed that Mr. O’Brien understated his personal wealth.

Back in 2016, Hulk Hogan (backed by billionaire Peter Thiel) won a libel lawsuit against Gawker that drove the publication out of business. That proved the power to sue is the power to destroy. But even threat of lawsuits can chill speech.

The Sandmann lawsuit similarly seeks to wipe out much of the value of the Washington Post. The $250 million demand represents the amount of money that owner (and frequent Trump target) Jeff Bezos paid for the newspaper in 2013.

Realistically, of course, the suit is unlikely to bring the Washington Post to its knees, but for smaller publications in a declining industry, even filing a lawsuit can pose an immediate existential threat. Well-heeled litigants can crush media critics simply by starting the legal meter running.

Experience suggests that it is naïve to thinking that gutting the libel laws will affect only statements of fact or would be used simply to target egregious errors. In an age of ideological and cultural hand-to-hand combat, the lines between fact, opinion, and analysis can quickly blur.

The Sandmann lawsuit illustrates the process. Yes, the media behaved badly in the coverage of the confrontation between students from Covington Catholic and protesters on the Mall. Mistakes were made, and reputations were unfairly maligned. But the $250 million suit does not merely target the errors of fact. As a writer in Vanity Fair notes:

Whatever its merits, the lawsuit itself reads like an overtly partisan political statement. [Sandmann’s lawyers] claim that the Post “wanted to advance its well-known and easily documented, biased agenda against President Donald J. Trump (“the President”) by impugning individuals perceived to be supporters of the President.” They also claim that the Post’s coverage of the Covington incident was part of a campaign “in furtherance of its political agenda . . . carried out by using its vast financial resources to enter the bully pulpit by publishing a series of false and defamatory print and online articles which effectively provided a worldwide megaphone to Phillips and other anti-Trump individuals and entities to smear a young boy who was in its view an acceptable casualty in their war against the President.”

Perhaps inevitably, the filing of the suit drew applause from a Trump tweet:

The Conservative Temptation

This will be immensely appealing to Trump’s conservative base. As Trump has learned, attacking the “fake news media” is the reddest of red meat and has the added advantage of feeding his own obsession with discrediting his critics. Having marinated in distaste for the media for years, conservatives will be tempted by the opportunity to strip the press of its legal protections.

But embracing the Trump/Thomas position would be a dangerous and ultimately self-defeating mistake. It would also be an ironic retreat on the issue of free speech. In recent years conservatives have embraced the First Amendment to push back against the stifling environment on some university campuses; and have adopted sweeping interpretations of its protection on free speech to invalidate a host of campaign finance laws.

In the very recent past, conservatives were appalled and outraged by suggestions that the federal government restore the Fairness Doctrine as a way of regulating and reining in conservative talk radio. They rightly saw the doctrine as restoring a form of “speech police,” who could be used to chill and harass the expression of unpopular (read conservative) opinion.

Pre-Trump, conservatives understood that their support for a free press was based on both principle and prudence. A weapon that can be used to shutter liberal media outlets can just as easily be turned against conservative activists, publications, and outlets.

Lawsuits are unlikely to put the New York Times or CNN out of business, but can the same be said of outlets like Breitbart, the Drudge Report, or the Daily Caller?

Billionaire litigants could make life miserable for Jim Acosta or Rachel Maddow; but billionaires on the left could also bankroll devastating legal attacks on talk radio hosts and right-leaning bloggers. The schadenfreude on both sides would be exceptional, but the price tag for democratic debate would be catastrophic.

So conservatives will once again face a choice in the Age of Trump, and this one may be distasteful for some, because they would be siding with the folks in the media they have been taught to loathe.

But this is the price of freedom and it is the genius of the Constitution that they claim to revere. By all means, conservatives should continue to criticize media malpractice when they see it; but they also need to reaffirm their support for “the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open.” It was, after all, Ronald Reagan who declared:

There is no more essential ingredient than a free, strong and independent press to our continued success in what the Founding Fathers called our 'experiment' in self-government.