Cormac McCarthy and the World’s Horrible Unknowability

His new novels deserve to be remembered as the literary event of the last decade.

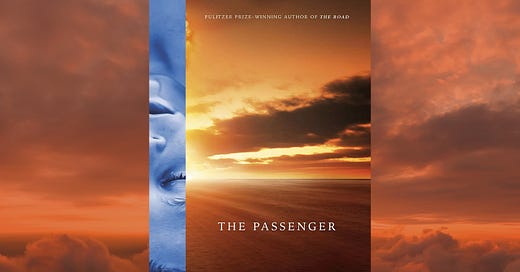

For many years, fans and admirers of the writer Cormac McCarthy wondered if he would ever publish another novel. He was getting on in years (he’s currently 89), and he’d hit such a professional peak with his previous book, The Road (2006), that it was hard to avoid the sinking feeling that, as great as his fiction tended to be, we might have seen the last of it.

And maybe The Road was to blame. McCarthy was not exactly a writer from whom one expected a breakout hit; the prose in his early novels, especially Blood Meridian, could be described as the Old Testament by way of James Joyce. But with The Road (which won the Pulitzer Prize, prompted Nobel whispers, and landed him on Oprah) he now had two. All the Pretty Horses (1992) won an armful of awards itself and wound up a genuine bestseller. It was also the first of four McCarthy novels adapted to film (that is, if you count James Franco’s film version of Child of God, which I’m not inclined to do, but technically I think I have to). So maybe the slowly building and outsized wave of fame (which is not to say undeserved, but I doubt McCarthy saw any of this coming) somewhat overwhelmed him. These things happen. There was an eleven-year gap between Charles Portis’s True Grit and his follow-up The Dog of the South. Joseph Heller was virtually paralyzed by the success of Catch-22, though he eventually broke out of it. Ralph Ellison did not publish another novel in life after Invisible Man.

And so, for years, following The Road, there was nothing—until information started leaking out about a “long novel” called The Passenger, that it had something to do with a woman’s suicide, and that this would be McCarthy’s next book. This itself went on for years, until it was then announced that the manuscript of The Passenger was going to be sealed with the rest of McCarthy’s papers at the University of Texas. To me, this sounded unpromising. Maybe McCarthy was unsatisfied with it, or found himself incapable of finishing it. But then, suddenly, in early 2022, Alfred A. Knopf announced that they would publish the novel, though it would now be two novels: The Passenger would publish first, and then its companion piece, once integrated into the greater whole, Stella Maris would come out about a month later (despite the decision to split the novel into two, the assertion that The Passenger would be a “long novel” is fairly misleading as the two books together don’t even add up to 600 pages). The two books comprise what I can only see as the American literary event of the last decade, and it would be really cool if one day it were acknowledged as such.

The Passenger centers on several months in the life of Robert Western. Much of the novel’s action takes place in New Orleans and its surrounding areas. Western works as a salvage diver—a job that sends him to crash sites throughout the South—and early on he and his friend and diving partner, Oiler, find themselves in Mississippi. There, they find a plane submerged in a lake. This crash has not been on the news. Furthermore, the plane seems free of any damage, like it just appeared in the water. Everyone on board—seven passengers and the two pilots—are inside the plane, dead. Western and Oiler subsequently learn that there should have been eight passengers. One is missing, as if they’d simply swam to the edge of the lake and walked ashore.

This would have to be counted as The Passenger’s central mystery, though what any of it means is left to the reader to suss out. McCarthy is not concerned with providing traditional narrative satisfaction here. Besides, there’s still a lot to get to. Among other things, The Passenger addresses questions of physics, philosophy, mathematics, historical violence (something that has long concerned McCarthy in his fiction; people often forget that Blood Meridian is roughly based on historical fact), booze and drugs, suicide, insanity and genius, the JFK assassination, and heritage. The story is broken into paired chapters, the second set in the “present day” of Western’s world, the first in the past, around 1970 (although this structure is not rigorously adhered to in the later stages of The Passenger). In the sections set in the past, Western’s young sister Alicia, whose suicide occurs on page one, is in her bedroom, night after night, while a group of traveling, somewhat sinister entertainers (led by the very short, scarred, and flipper-handed Thalidomide Kid) appear, as they’ve been doing for years, to tell bad jokes, perform minstrel routines, and generally annoy her. Their motivation is somewhat obscure to the reader and to Alicia—as is the relative reality of these beings—but the Kid, at least, acts as a kind of blunt psychiatrist. One who gets nowhere with the strong-willed and brilliant Alicia, it must be said. This is mirrored in Stella Maris, which consists entirely of dialogue from therapy sessions between Alicia and her therapist in Stella Maris, a mental hospital in which Alicia has voluntarily committed herself.

Over the course of The Passenger, two of Western’s friends—friends the reader has spent much time with—die. I won’t say who they are (Western has a lot of friends in New Orleans), but there doesn’t seem to be any reason to suspect any cause of death beyond what we are told. Well, maybe there’s a reason to wonder about one of them, but the point is that either way, there’s a mysteriousness to these incidents that’s hard to put a finger on. This vague feeling is bolstered somewhat in one scene when a character stumbles across Western in a bar, and the two of them just start randomly discussing the Kennedy assassination. Western is very much of a conspiratorial frame of mind about all this, and it will perhaps remind the reader that Western is being sought by a couple of CIA types (though not necessarily CIA) regarding the crashed plane in Mississippi. And also there’s the historical violence aspect of it all. Western talks about the Zapruder film, and how in that brief footage you can see Jackie Kennedy attempting to retrieve pieces of her husband’s obliterated skull. But if it was possible to conspire to kill a president of the United States, how hard could it be to take out a couple of Western’s friends? Or one of them.

Western’s father worked closely on the Manhattan Project. That’s where his parents met, in fact. Their father went to Japan after the bombs had been dropped:

[The living] were like insects in that no one direction was preferable to another. Burning people crawled among the corpses like some horror in a vast crematorium. They simply thought that the world had ended. It hardly even occurred to them that it had anything to do with the war. They carried their skin bundled up in their arms before them like wash that it not drag in the rubble and ash and they passed one another mindlessly on their mindless journeyings over the smoking afterground, the sighted no better served than the blind.

Not only does this tie Western and Alicia to the greatest horrors of the last century—which seemed at times as if it might literally be the last one—but also to the sciences that obsess them both. Alicia is/was a brilliant mathematician (who nevertheless, she tells her therapist in Stella Maris, thought frequently about giving it all up) with a deep and abiding interest in physics, and the men and women who put in the work. Not just to create the atom bomb, but to, if at all possible—and neither Alicia nor her brother are altogether sure it is—advance human knowledge in understanding the fundamental truths of existence, and what happens when we stop existing. Both Western and Alicia sound like atheists throughout their respective novels, but neither of them quite manages to fully disbelieve. In Stella Maris, Alicia seems almost mournful, or at least disappointed, that she can’t quite commit to a non-belief in God, not least because if she believes there is a God, she is unable to take any comfort in it.

There is a lot of discussion about the hard sciences in both of these books. One scene, one of the least graceful of McCarthy’s career, I have to admit, has a character we’ve never met before (or will ever meet again) stumble across Western in a bar, whereupon the two men just start talking about physics for pages, including mini-scandals having to do with the Nobel Prize in that field. And while I’m sure there are many people who will understand exactly what McCarthy is talking about in these scenes, I can’t imagine that making the rest of us fully comprehend it was the primary goal for McCarthy. He’s plunging the reader into the (at times frustrating) complexity and unknowable nature of the world, and our place in it. If these physics theories are truly the path to ultimate knowledge, the basic uncertainty at the root of it all—they are, at the end of the day, just theories—almost renders the point moot. We’ll never have the answers, nor will any of the people working on the questions, so God is as likely, or as unlikely, as anything else. In Stella Maris, Alicia relates a story to her therapist about the time the intense and seemingly constant crying of babies sank into her brain and made her wonder why they all screamed in apparent agony all the time:

The more I thought about it the clearer it became to me that what I was hearing was rage. And the most extraordinary thing was that no one seemed to find this extraordinary. . . . The rage of children seemed inexplicable other than as a breach of some deep and innate covenant having to do with how the world should be and wasnt. I understood that their raw exposure to the world was the world.

So this brother and sister pair go through life together, with the weight of the universe inside their heads. Perhaps this is why they fall in love. And by that, I mean romantic love, even carnal love, though each of them, in their respective novels, insists the carnal part was never consummated. But Alicia, especially, could not imagine a life where the one man it was possible for her to love that completely refused the kind of love she wanted, even though, she knew, he shared her desire. For this and every other reason, she killed herself. Unless she didn’t, and in fact Western, as Alicia tells it in Stella Maris, was horribly injured in a car race, and was, in the early ’70s, while Alicia tells her story, laying in a coma in Italy, braindead.

Or, if Western in The Passenger, which takes place in the ’80s, is to be believed, he recovered from that injury, albeit with more metal plates in his body than when he entered the hospital, and it was in fact Alicia who was dead, hanging by her neck from a tree, in the early morning winter light. Unlike some readers, I’m not convinced that Stella Maris refutes the facts as presented in The Passenger, and that the entirety of the longer novel is the product of a braindead mind. Either could be true. Hell, after all that, both could be true. We’ll never know. We’ll never know anything that is truly important.