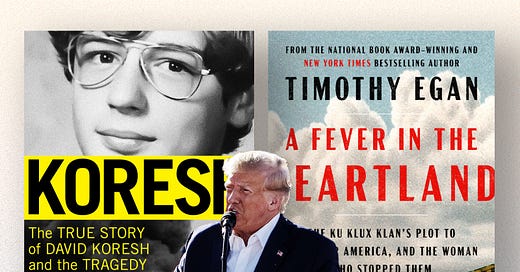

David Koresh, the KKK, and Donald Trump

Two new books help explain the phenomenon of cult figures.

Koresh The True Story of David Koresh and the Tragedy at Waco by Stephan Talty Mariner, 464 pp., $35

A Fever in the Heartland The Ku Klux Klan’s Plot to Take Over America, and the Woman Who Stopped Them By Timothy Egan Viking, 432 pp., $30

In 1987, the man who would soon change his name to David Koresh was locked in bitter contention with a rival leader of the Branch Davidians over who was the rightful owner of Mount Carmel, the 77-acre compound that served as the cult’s headquarters near Waco, Texas. The rival leader, George Roden, suggested a way to resolve the dispute.

There was a cult member, Anna Hughes, who had died two decades earlier and was laid to rest in a makeshift graveyard. As Stephan Talty relates in his new book, Koresh, Roden unearthed Hughes’s coffin and announced that “whichever of them could bring Anna back to life would prove that he was the son of God and the true owner of Mount Carmel.” Koresh, then still known by his birth name of Vernon Wayne Howell, waited to see what his rival would do.

Roden moved the casket into the chapel in Mount Carmel, where he banged gongs and howled at the moon, all to no avail. Koresh, for his part, went to the local sheriff and reported Roden for having dug up a corpse.

He was an avowed cult leader who believed in lots of crazy things, but he was not stupid.

As it turned out, the sheriff’s office felt there was not enough evidence and declined to take action. The feud between Roden and Koresh ultimately escalated into a gun battle that left Roden injured and Koresh and several of his cohorts in jail. No one was convicted, and the men’s guns were returned to them. But the experience left an awful taste in Koresh’s mouth, prompting his pledge to a deputy, “You’ll never lock me up again.”

He was right. When FBI agents attacked the compound on April 19, 1993, after a 51-day standoff, Koresh ordered its immolation, killing himself along with 75 of his followers, including 18 children ages 10 and under. Talty’s book is set for release on April 11, just before the thirtieth anniversary of this cataclysmic event that continues to serve as fount of anti-government sentiment among the far right.

Donald Trump picked Waco, of all places, for the first mass rally of his third bid for the presidency. There, with characteristic unsubtlety, he stood at attention, hand over heart, for an homage to the violence of January 6th, including a song performed by a choir of incarcerated insurrectionists. He assured his audience that “the thugs and criminals who are corrupting our justice system”—by holding Trump to account for his violations of law—“will be defeated, discredited, and totally disgraced.” He intoned, with Koresh-like prognostication, that “2024 is the final battle, it’s going to be the big one. You put me back in the White House, their reign will be over and America will be a free nation once again.”

Talty, whose previous nonfiction books include A Captain's Duty, co-written with its subject and later made into the Oscar-winning film Captain Phillips starring Tom Hanks, does a fine job of shining light on the mechanisms of cult control, as practiced by a sadistic bully. In this respect, Koresh is deeply similar to another book, out this week and timed loosely to the centennial of the emergence of the nation’s premiere hate group as a major political force.

A Fever in the Heartland, by Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Timothy Egan, also focuses on an incomprehensibly charismatic figure: the Klan leader David C. Stephenson, who went by D.C. Stephenson, or “Steve.”

Born into wealth with an ingrained sense of privilege, Stephenson rose through the ranks in the early to mid-1920s to become Grand Dragon in Indiana, then the nation’s leading hotbed of Klan activity, both in numbers of adherents and the depth of its influence in the political sphere. In 1924, the Klan boasted 400,000 Hoosier members, which was probably only a slight exaggeration. The state had a Klan-affiliated governor, Ed Jackson; its capital city of Indianapolis had a Klan-backed mayor, John L. Duvall; and one of its U.S. senators—James Watson—was, as Egan puts it, Stephenson’s “loyal supplicant.” All three were Republicans, as were countless local officials, judges, district attorneys, sheriffs, and police officers in Indiana who supported the KKK.

Observed the New York Times in November 1923, “In no State in the Union, not even in Texas, is the domination of the Ku Klux Klan so absolute as it is in Indiana.” But the Klan’s political influence extended nationwide, as Egan relates: “About seventy members of Congress were faithful to the hooded order, by the Klan’s tally. It had sympathetic governors in Georgia, Alabama, and California.”

The Klan found its sense of common identity in hatred of others, including black people, Jews, Catholics, and immigrants. Georgia Gov. Clifford Walker, speaking at a Klan rally in 1924, said the United States should “build a wall of steel, a wall as high as heaven” to keep out immigrants. The Klan had a women’s brigade and even a children’s chapter called the Ku Klux Kiddies, who, Egan writes, “were issued small-sized robes and masks, recited pledges and songs at regular den meetings, and marched in parades.”

In the summer of 1925, some 50,000 Klanspeople marched down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., with a crowd of 200,000 spectators cheering them on. The Washington Post called it “one of the greatest demonstrations this city has ever known.”

It was D.C. Stephenson, perhaps more than anyone, who was responsible for the Klan’s success. His eventual undoing, as much as anything else, spurred the Klan’s demise. And this undoing was brought about, more than anyone or anything, by the courage of a young woman of his acquaintance named Madge Oberholtzer.

I’ll come right out and say it: Part of what makes these two books about terrible episodes in U.S. history relevant is the insight they offer on an important contemporary subject—namely, the persona and phenomenon of Donald Trump and other authoritarians who continue to find their way onto the world stage.

Let me be clear, since there is an entire cottage industry of wags devoted to distorting comments like the one I just made: I do not think Donald Trump is exactly like David Koresh or D.C. Stephenson. Trump is obviously a racist, but I don’t think his heart is full of hatred for others based solely on the color of their skin. (I think that, on some level, he is a classic misanthrope, hating everyone but himself.) And I don’t think he is a cult leader so much as a “cult of personality” leader.

But the parallels are worthy of attention. There is in human nature an appetite for obedience to figures like Koresh, or Stephenson, or Trump. (Even Mike Pence succumbs to it, despite Trump’s having “endangered my family and everyone at the Capitol that day,” as he said in a room where no cameras were allowed.) And it is worth employing a brain cell or two trying to understand what this larger phenomenon is about. How can these men dupe their supporters so thoroughly? How can they command allegiance when all they offer in return is disrespect?

One of Stephenson and Koresh’s tools for securing the allegiance of others was denigration; they simply disparaged them into submission. Their cruelty was amplified by a sense of invincibility. Their self-regard was so overwhelming that it pulled other people into their orbit. These are features that are clearly shared by Trump.

Koresh’s upbringing was much different from Stephenson’s, though they both came to develop the same set of skills. Koresh’s mother was not yet 15 years old when he was born in Houston, Texas. His father left them for another teenage girl and his stepfather was replaced with a violent alcoholic, who abused them both. He was bullied as a child. “They chanted ‘Retard, retard,’ or ‘Four eyes,” Talty writes. “After third grade, they switched to ‘Mr. Retardo,’ which stuck for years.”

After an illegal sexual relationship with a 15-year-old girl, which led to the first of his many children, David found his way to Waco, where he took up with the Branch Davidians, a pre-existing cult. He prophesied his way into leading the Davidians, with a keen understanding of what it was about.

“Well,” he once told Marc Breault, one of his closest associates, who spoke to Talty, “just look at us. You know we’re in a cult. We’re actually in a cult.” He laughed, adding, “I mean, do you ever fear I might turn into another Jim Jones and give y’all the Kool-Aid?”

Koresh would regularly inflict beatings on children of the Davidians, including his own—even when they were still infants—and depravations on his followers. He felt entitled to sexual congress with any woman or girl who happened to be available. It was, in part, a way to break down his followers. As Talty relates, “It was as if having sex with the Davidian wives was just half the thrill for Vernon. He also wanted to humiliate the men, revel in their pain.”

Stephenson—like Koresh and, allegedly, our former president—was a serial sexual assaulter. The people around him became acclimated to the sight, in Egan’s words, of “battered and bloody women who fled hotel rooms in tears and torn clothes, the Grand Dragon passed out and smelling of bourbon and tobacco.” He got away with it more than once. And he would have kept on getting away with it had Oberholtzer, a young woman who lived with her parents not far from Stephenson’s enormous Irvington residence, not made a sworn deathbed declaration of how he kidnapped her, raped her, and bit her so hard with his teeth that he caused her to bleed profusely. She ended up poisoning herself while still in his clasp, hoping to end the ordeal.

While it was clear from the start that Oberholtzer would not survive, the painful process took nearly a month.

Stephenson was charged and brought to trial, spewing indignation. He decried his prosecution, Egan writes, as “a hoax and a witch hunt.” He was set up; it was all so unfair. He proclaimed in the third person that “D.C. Stephenson is not guilty of murder in any degree.” He called the trial “the most appalling persecution to which man has been subjected to since the days that civilization abandoned the bludgeon.” After a guilty verdict was rendered, his attorneys filed a motion listing 387 reasons that he was wrongfully convicted.

Stephenson filed more than 40 appeals, all unsuccessful; he served nearly 25 years in prison.

Stephenson’s fellow klansman in the governor’s mansion, Ed Jackson, was later indicted on bribery charges but got off on a technicality, while the Indianapolis mayor, John L. Duvall, was convicted of violating the state’s corrupt practices law and locked up.

In addition to Oberholtzer, whose tragic end exposed Stephenson’s meanness to the nation, a number of heroic people stood in opposition to the Klan leader. These include Stephenson’s prosecutor, Will Remy, who imperiled his health and dipped into his own wealth taking on the Klan. When Stephenson got authorities to cut off funds for the prosecutor’s office, Remy “was forced to reach into his own pocket to buy law books, office supplies, and stenographic material, and to arrange for [the] transport of witnesses.”

There was also the journalist George Dale, who poured his life’s energy into opposing the Klan. “His weapons were satire and wit,” Egan relates. “When a local Klan den proclaimed that Jesus was a white Protestant, Dale pointed out that Jesus would have been banned from the Klan—as a Jew and an olive-skinned alien.” On Stephenson’s orders, Dale was attacked and beaten. A judge he had mocked even threw him in jail after he asked for the men who had beaten him to be arrested. His family was threatened.

“Dale was nearly bankrupt, his credit no longer good at the grocery store, his paper running on fumes,” writes Egan. “But so long as [he] still had an ounce of ink to spill, he spilled it on the Kluxers, as he called them.” Dale assessed that the Klan was akin to typhoid fever and needed to “run its course” through the body politic.

In the case of Koresh, it was his good friend Mark Breault who turned against his former master. Breault “had a revelation, as sharp and strong as his angel vision when he was a boy. The Davidians under [Koresh] were a Satanic movement. He would fight it.”

Both of these compelling books arrive at a time when Trump is on the verge of two opposite and almost equally plausible outcomes: He might either get his comeuppance or return to power. His MAGA movement is not a revival of the KKK or Branch Davidians, to be sure, but it gets its charge from some of the same currents that animated those earlier movements, including the willingness of ordinary people to be subject to the authority of a deranged leader. All represent a dive into darkness, a retreat from democratic ideals and from rationality itself, a maladaptation that must be met with courageous opposition.

Where is the revelation that will break the spell of MAGA-land? When will the fever run its course? And what can we do, individually and collectively, to help make that happen?