Democrats Are Better at This

Four years ago the Republican party rolled over for a populist charlatan. This year, the Democratic party fought back against their own populist—and won.

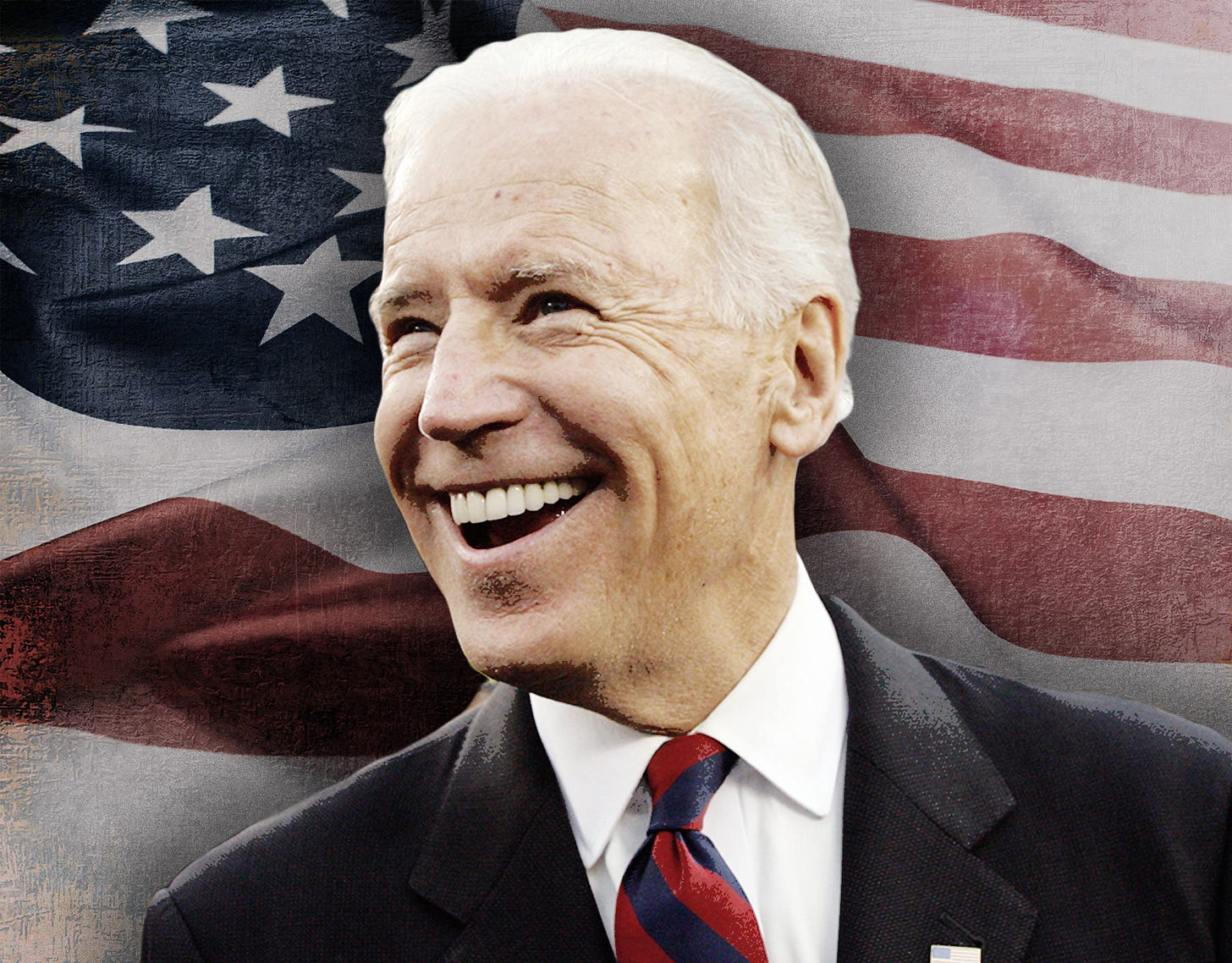

Seventeen days ago I sent up a flare to mainstream Democrats. Based on my experience trying and failing to stop Donald Trump in 2016, I warned that “barring a drastic change in the race, Bernie Sanders is going to be the presumptive Democratic nominee 11 days from now.” Well, drastic change has come and Democratic primary voters were the change that they sought. With his victories tonight in Michigan, Missouri, and Mississippi, Joe Biden is set to be the nominee of the Democratic party—barring some unfathomable turn of events far more drastic than what was required 17 days ago. How did it happen? How did the Democratic mainstream achieve what Republicans could not in 2016? What were the antibodies, strategic choices, and circumstances that made them more able to defeat a populist insurgency? Here’s how.

(1) The Democratic Coalition Is Less Susceptible to a Populist Charlatan

The Democrats’ national coalition in 2020 was not immune to charlatans or populists but, unlike the Republicans, it made them constitutionally capable of staving one off. Republican elected officials, strategists, and pundits spent the weeks leading up to Super Tuesday gleefully mocking anti-Trump Republicans and Democrats as the party looked to be stumbling towards nominating Bernie. They claimed that it proved what they had argued all along—that Trump was just a natural reaction because it was the Democrats who were really the crazy ones. The past two weeks have destroyed these arguments. The Republican commentators didn’t understand that the Democratic party is hardier than the GOP was. The Democratic coalition isn’t as reactionary. The strong Democratic voting blocs aren’t as easily seduced by grifters. This isn’t an opinion. It’s just a plain fact. Look at the numbers. What many of us on the inside had seen coming—but believed we could ward off—was that the Republican party had become ripe for a populist revolution after decades of shedding college-educated, professional-class voters and trading them for working-class voters. The problem here wasn’t that the college-educated voters were better or worse than the working-class voters—the problem was the disequilibrium this shift created. Because it left a vestigial Washington-class of corporate Republican types resenting a growing base that felt neglected and rejected by them. The new voters who came into the party were drawn to the GOP on largely cultural grounds and were not particularly enchanted by the Ryanomics that party elites had been offering since 1980. According to Pew’s political typology breakdown in 2017, these “market skeptic” Republicans made up about 20 percent of the party. They were a substantial voting bloc and their ranks have only grown in the ensuing years, both as more voters joined them and as members of the Washington Republican class switched sides so as not to lose access to power. On top of the influx of working-class, free-market skeptics, the evangelical base of the party proved deeply susceptible to populist insurgency. Prior to 2016, the “true conservative” theory of the case was that the ideological homogeneity of evangelicals would allow them to play the role of gatekeeper against a hedonistic, populist insurgency. That assumption was not crazy—though the careers of Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, Jim Baker, and Oral Roberts might have suggested otherwise. It did, however, turn out to be incorrect. The decades of resentment against elites primed evangelical voters to rally behind someone who was willing to fight and anger those elites. What this left in the Republican coalition was a small group of purely ideological and devoutly religious (especially Mormon) voters uniting with the waning number of what used to be known as country-club Republicans to stave off Trump. The numbers were so overwhelmingly against them that even the country-club Republicans quickly decided to join a new club and put on a red Mar-a-Lago visor. In the end, it was the rare wisdom of Rep. Thomas Massie that best encapsulated the situation. The majority of Republicans weren’t either ideologically motivated or motivated by competent governance. They just wanted to support “the craziest son-of-a-bitch in the race.” The Democratic electorate just didn’t share the level of anger and antipathy—or have the same death wish—no matter how many Republican pundits wishcast it upon them.

(2) Donald Trump Focused the Democrats’ Minds

The exodus of college-educated suburbanites from the Republican party has been the Democrats’ big gain in 2020. These formerly Republican, independent, and swing-Democratic voters gave Pelosi the speakership in 2018 and have now moved fully into the Democratic camp. Virginia offers a telling example. In Fairfax County, over 100,000 more people voted in the Democratic primary this year than in 2016 (!!), with an increase in those who described themselves as “moderate” or “conservative” and a relative decrease in those who described themselves as “very liberal.” Michigan State political scientist Matt Grossman used exit polls to re-weight the 2016 Republican primary to put these “moderate” Virginia voters back into the GOP pool and found Rubio would have won the state over Trump. So the very voters whom Trump turned away from the Republican party ended up going over to the Democratic side and helping put the more centrist candidate over the top. More significantly, black voters—who make about about 24 percent of the Democratic primary electorate—stamped out the far-left populist candidate for the second straight cycle. It was these black voters who gave Biden the oxygen he needed to win. It turns out that black voters were for Democrats what Republicans had assumed evangelicals would be for the GOP. There have been several deeply reported articles about how black voters came to play this critical role in Democratic politics, and they all come to a similar general conclusion: Black voters made a pragmatic choice driven by who they think can beat Trump. Call it the inverse of the Massie Corollary—they didn’t want to risk four more years of Donald Trump on the craziest son-of-a-bitch in the race. Instead, they picked the most palatable and trustworthy son-of-a-bitch they could find. The suburban swing voter and black voting blocs were joined by the urban NPR/The Daily-listening liberal who hates Donald Trump so much that she would prefer getting COVID-19 to having him in office next January 21. These voters, who in another situation might’ve been Bernie-curious, were not about to let Donald Trump spend six months calling them commie-sympathizers. They were highly engaged and informed throughout the process and were willing to shed ideological considerations in order to support the candidate who looked to have the best chance to win. Put together, these groups created a wall that was impenetrable for Bernie’s populist campaign.

(3) Democratic Leaders Were Up to the Task

I wrote about the skittishness that I saw in 2016 when approaching GOP leaders about coming out against Trump. These elites realized the inmates had taken over the asylum. And they were either too scared to get in the way of a base they knew was primed to overthrow them, too eager to be the first person to nuzzle up to their new daddy (Hi Chris Christie!), or simply unwilling to use their political capital in such a way that it might benefit someone they hated (translation: Ted Cruz). Once again, the Democrats did it better. Democratic party leaders were willing to take on the risk of alienating Sanders and his base for the good of their party. First it was Jim Clyburn who buoyed a shaky Biden ahead of South Carolina. Then Mayor Pete and then Amy Klobuchar bowed out as soon as they were non-viable and eagerly led a 3-day deluge of former foes as they marched to endorse Biden. Because the Democrats had an electorate that was uber-engaged, pragmatic, and focused on beating Trump, it only took those 72 hours for the preponderance of the electorate to get the message: Bernie wasn’t inevitable. The party could do better. And so they have.