Do You Want to Know a Secret?

Trump’s behavior warrants prosecution, even if the classified materials he expropriated aren’t all that dangerous.

In the basement of my home I keep a document that reveals a closely guarded secret of H-bomb design. The administration of President Jimmy Carter said its disclosure would cause “grave, direct, immediate, and irreparable harm” to the national security of the United States. Carter, a nuclear engineer by training, personally signed off on the effort to keep this secret from being spilled, writing at the top of U.S. Attorney General Griffin Bell’s memo spelling out this intent: “Good move, proceed. J”

The document is an article in the November 1979 issue of The Progressive, a small, iconoclastic national magazine based in Madison, Wisconsin. It was originally slated to run in the magazine’s May 1979 issue. But for six months and 19 days, The Progressive was forbidden, by order of a federal judge, from publishing or otherwise “communicating, transmitting or disclosing” the article’s contents. It was only the second time in U.S. history that the federal government sought to block publication, known as prior restraint, on national security grounds; the first was in 1971, when the administration of President Richard Nixon sought to suppress the Pentagon Papers.

In this case, an injunction preventing The Progressive from publishing an article by freelance writer Howard Morland was issued by federal Judge Robert W. Warren, a Nixon appointee. He bought the government’s argument, calling the article “the recipe for a do-it-yourself hydrogen bomb” and proclaiming “I’d like . . . to think a long hard time before I gave the hydrogen bomb to Idi Amin.”

None of this was true. Building an H-bomb requires years of work and the investment of many billions of dollars. You can’t do it in your garage. While Morland, a former Air Force pilot, did uncover a concept of hydrogen bomb design known as the “Teller-Ulam configuration,” it was hardly a well-kept secret. He proved that by uncovering it with no scientific training. (Other journalists and amateur nuclear sleuths were also able to derive the concept from cursory research after the government’s action to suppress the story became known.) Erwin Knoll, the magazine’s editor, told the government he was “incredulous that a writer with Morland’s limited background . . . could so readily penetrate what you are describing as perhaps the most important secret possessed by the United States.”

Knoll, previously a reporter for the Washington Post, had seen often how government officials used claims of secrecy to evade accountability and cover up abuses. He took an especially dim view of nuclear secrecy—predicated on the dubious notion that, were it not for seditious breaches, “they” might not figure out how to build “our” bombs. By this time, four nations besides the United States had independently mastered this achievement, no thanks to the Rosenbergs.

The lie that the expansion of nuclear weapons depended on access to some sort of secret high-level scientific knowledge was, Knoll believed, responsible for nearly all of the political repression—the spy scares, the witch hunts, the loyalty-oath purges—that had stymied progressive change in Cold War America. So Knoll and the magazine eagerly accepted the opportunity to directly challenge the nuclear-secrecy mystique.

As the case played out, The Progressive and its lawyers were barred from showing the article to anyone who lacked security clearance, making it much more difficult to mount a defense. Court filings were stripped of references to other articles that had previously appeared in magazines and encyclopedias. Affidavits were submitted on behalf of Knoll and other defendants that they were not allowed to see. On the basis of court proceedings they were not permitted to attend, decisions were handed down in their case that they were prohibited from reading.

But still, the magazine and its supporters were able to sway public opinion mostly to their side.

In the end, the government had to drop its case against The Progressive after the “secret” it was trying to shield was revealed by multiple others—further proof, if any were needed, that the “restricted data” were not much of a secret. Morland’s article is not just in my basement; you can read from the magazine’s archive’s here. I gave a full account of the H-bomb case in my 1996 book, An Enemy of the State: The Life of Erwin Knoll; for an abbreviated one, see “The H-Bomb Case Revisited.”

Two decades after writing my book on Erwin, I became editor of The Progressive, which this month turned 114 years old. The story of the H-bomb case has always informed my understanding of debates over the alleged danger to national security posed by the release of purportedly sensitive information. Count me as skeptical.

Obviously, there are secrets that the government keeps because it’s a good idea to keep them. But how much of what’s classified genuinely needs to be kept secret, and how much is classified because the government engages in overclassification?

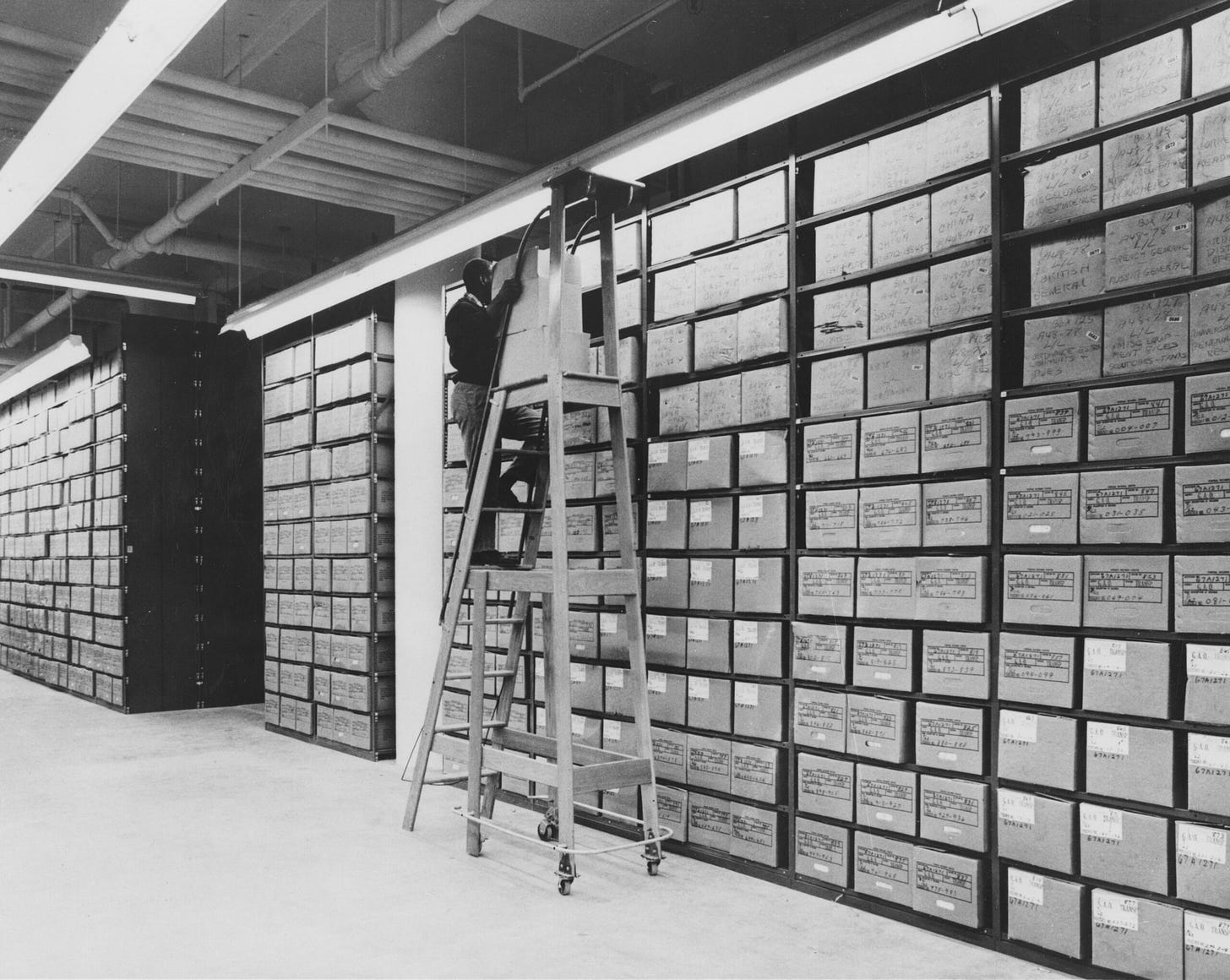

“I’ve seen a couple-million pages of documents that were classified when the government put them on paper or computer screens,” wrote Thomas Blanton, director of the independent nongovernmental National Security Archive at George Washington University, in a 2015 Washington Post op-ed. “I can say from experience that few deserved such consideration.”

Blanton was responding to the national conniption fit, which in some quarters is still going on, over Hillary Clinton’s emails. According to the always unreliable Donald Trump, the Clinton email debacle constituted the greatest threat to national security in the history of the nation—that is, at least until it emerged that President Joe Biden committed an even greater breach by having a much smaller number of classified and improperly maintained documents. The day before additional classified documents were discovered at Biden’s Delaware residence, Trump went berserk.

“At the very same moment when my ultra-secure Mar-a-Lago home was raided by the FBI, Joe Biden was harboring classified documents in his China-funded Penn Center and his unsecured garage,” Trump declared in a January 19 video rant. He lamented this situation transpiring “while I’m being persecuted by Trump-hating special counsel—I call them special prosecutors but this one in particular, he’s a prosecutor and a Trump-deranged person.”

Trump, naturally, sees Biden’s self-reported misplacement of a small number of classified documents as being vastly more serious than his own months-long campaign to prevent the government from recovering hundreds of pages of documents he improperly acquired. As Trump assessed it, “The difference is that while I did everything right—I did nothing wrong—Biden did everything wrong.”

Of course, as is often the case when Trump speaks, the opposite is true. There are many important things we do not yet know about either situation: chiefly, what was actually in the documents improperly stored by either man, and how those documents came to be improperly stored. Biden’s nonchalance (“There is no ‘there’ there”) about the stream of disclosures that he had classified materials lying around various places in his life may be regrettable and even blameworthy. But what Trump did sure looks like it’s criminal.

Trump took records that he knew did not belong to him and proclaimed that they did; he falsely claimed that he did not possess them and refused to return them when asked. Even if the documents pried from Trump’s possession do not pose a threat to national security, he deserves to face criminal charges for his mishandling of the situation and flagrant violation of the Presidential Records Act.

As Jonathan V. Last recently observed, “it’s not the documents [but] the obstruction” for which Trump is in hot water. “What we absolutely do know is that Biden’s team appears to have handled the breach by the book.” So, it seems, has former Vice President Mike Pence in responding to his lawyer’s newly announced discovery of classified documents in his house.

In contrast, “Trump’s team attempted to deceive and obstruct so as to retain possession of the documents.”

Blanton, in his Washington Post op-ed, said “the real secrets make up only a fraction of the classified universe, and no secret deserves immortality.” Some secrecy, he argued, is actually detrimental to national security.

For instance, he noted, “the congressional inquiry into 9/11 concluded that secrecy had kept the American people—our best allies in the fight against terrorism—from engaging with the threat they faced.” Agencies with information about the danger of this sort of potential attack failed to share it with each other.

Some secrecy stems from the desire of agencies and officials to avoid being embarrassed by revelations about their own actions. This was certainly the case with the Pentagon Papers, as Erwin N. Griswold, the U.S. solicitor general who led the Nixon administration’s efforts to block their publication, eventually admitted.

In a 1989 piece in the Post, Griswold acknowledged that “there is massive overclassification and that the principal concern of the classifiers is not with national security, but rather with governmental embarrassment of one sort or another.” He went on to say:

There may be some basis for short-term classification while plans are being made, or negotiations are going on, but apart from details of weapons systems, there is very rarely any real risk to current national security from the publication of facts relating to transactions in the past, even the fairly recent past.

Blanton, in an interview with CNN last September, said his group, the National Security Archive, estimates that 70 to 80 percent of material deemed classified is overclassified, “meaning most of what the government classifies could be released in very short order.” For instance, he said, the 22 “Top Secret” emails said to be on Hillary Clinton’s email server “all turned out to be New York Times stories that have been forwarded to her by her staff that were about drone strikes in places like Pakistan, and the controversies around them.”

But when asked by CNN whether the documents retrieved by the FBI from Mar-a-Lago were maybe “just a bunch of New York Times stories,” Blanton said “I doubt it,” explaining that “those cover pages [being marked] in garish yellow and red” is “a screaming signal that this is really sensitive.”

Regardless of how sensitive this information is or isn’t, it was not Trump’s to keep. Blanton expresses his disgust over how the former president treated these documents “almost as souvenirs,” proclaiming them to be his own property. Blanton’s rejoinder: “Well, they’re not. They’re the U.S. government’s property, the American people’s property. You didn’t have a right to them.”

That is the essence and nature of Trump’s crime: Not that he possessed information that could pose a threat to national security, but because, in his vast carelessness, it would not matter to him if he did.

One reason so much information ends up being classified is that it literally is born that way. As the New York Times reported in 2016, all of the 113 Clinton emails determined to have classified information fell into a category of records known as “born classified” because of how they were obtained or generated, not based on an assessment of how sensitive they were.

The designation for being born secret traces to the 1946 Atomic Energy Act, which established that all information regarding the development of nuclear weapons is automatically classified at the moment of its creation. The act has since been expanded to include other issues. It was this act that the federal government invoked in its 1979 attempt to block The Progressive from publishing “The H-bomb Secret: How We Got It, Why We’re Telling It.”

But Morland’s article was not flagged because it fell into a certain category. It was determined to be, on considered reflection, among the most highly classified and dangerous information that could possibly get out.

And yet, it wasn’t.

Since the article was published, several more nations have joined the nuclear club, with no help from Howard Morland. A recent chart in Time magazine, citing information from the Federation of American Scientists, gave the “current count” of nuclear warheads as being Russia with 4,477 and the United States with 3,708. Here are the seven remaining nuclear countries: China, 350; France, 290; United Kingdom, 180; Pakistan, 165; India, 160; Israel, 90; and North Korea, 20.

A study released last August by scientists at Rutgers University found that even a limited exchange between nuclear nations using less than 3 percent of the world’s arsenal could kill a third of the world’s population within two years. A larger confrontation between the United States and Russia could lead to the starvation of three-quarters of the world’s population—while threatening the lives of virtually everyone in both countries by destroying agricultural capacity and contaminating water sources—in the same amount of time.

It’s possible something on a piece of paper in my basement or Hillary Clinton’s emails or Donald Trump’s closet or Joe Biden’s garage or Mike Pence’s house is going to make these weapons appreciably more dangerous. But I doubt it.