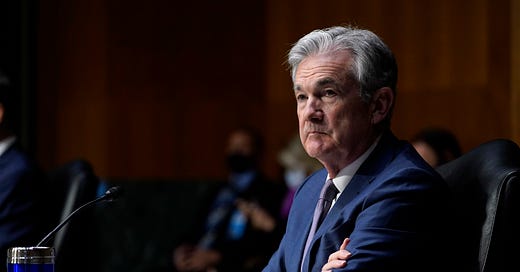

Fed Chair Powell Repeats Past Mistakes

His speech at Jackson Hole all but confirmed that the Fed will wait to curb inflation until it’s too late.

The late MIT economist Rudi Dornbusch used to say of the Bank of Mexico’s board members that he could understand their making mistakes—they were human, after all—but what he could not understand was how the same people could make the same mistakes time after time. He likely would have been similarly baffled by the current leadership of the Federal Reserve.

One can understand Jerome Powell’s Fed repeating one major policy mistake of the recent past. What is difficult to understand, however, is how it can be repeating a series of major policy mistakes in so short a time interval.

In the 1970s, high inflation hobbled U.S. economic performance and constituted a weighty tax on the most vulnerable members of our society. This high inflation was created in large part by an overly easy monetary policy—hence Milton Friedman’s famous law, articulated in 1970, that inflation “is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.”

Seemingly oblivious to the painful experience of the 1970s or to Friedman’s dictum, the Powell Fed has responded to the COVID-induced recession by allowing the money supply to increase at by far its fastest rate in the past fifty years. At the same time, as inflation accelerated to more than twice the Fed’s 2 percent target, the Fed keeps assuring us, as Powell again did last week in his Jackson Hole speech, that this inflation in not a monetary phenomenon, but is actually caused by supply-side bottlenecks that will soon be resolved.

By so doing, it seemingly dismisses any notion that the fastest inflation in more than thirty years might have something to do with the rapid rate at which the Fed has been printing money. It also seems to turn a blind eye to the fact that the Fed continues to pursue the easiest of monetary policies at the same time that the country is engaged in its largest peacetime budget stimulus on record.

Worse yet, the Fed seems to welcome at least some part of inflation’s recent acceleration, repeating, as did Mr. Powell at Jackson Hole, that it will tolerate higher inflation for some undefined period to make up for the lower-than-targeted inflation of the past few years. It does this despite having every reason to know that the time to squash inflation is before it gets really going.

If there is one aspect of monetary policy on which there is basic consensus among economists, it is that monetary policy operates with long and variable lags. Any action by the Fed will take some time to achieve measurable results in the economy, but the amount of time is unpredictable. This makes it all the more difficult to understand Powell’s Jackson Hole pronouncement that while the Fed might soon start tapering its bond buying program, it will wait until it sees the clearest of signs of more permanent inflation before it takes action to raise interest rates.

Many past inflationary episodes have taught us (or at least, should have taught us) that this will heighten the risk that by the time that the Fed acts to curb inflation, it will have been too late to have prevented inflationary expectations from becoming entrenched. Powell is like a hunter aiming at where the bird is, rather than at where it’s going to be.

Meanwhile, the Powell Fed has been ignoring the “everything” asset price and credit market bubble that it has been creating through its aggressive bond buying program. Indeed, in last week’s Jackson Hole speech, Powell made no reference to the equity and housing bubbles that the Fed’s ultra-easy monetary policy has created. Unlike in 2006, when it was only house prices that rose to levels disconnected from reality, this time practically all asset and credit prices have become seriously untethered from their underlying fundamental valuation.

U.S. equity valuations are now around double their long-term average—a level experienced only once before in the last 100 years. High-yield debt spreads are close to their all-time lows, while house prices are now rising by more than 15 percent a year and well exceed their 2006 peak.

And yet, the Fed will continue to buy $40 billion month in mortgage-backed securities at least until the end of this year at a time that the U.S. housing market is on fire, the economy is recovering strongly, and inflation is already uncomfortably high. Did the Fed really learn nothing from the painful experience of the bursting of the 2006 housing and credit market bubble?

It has often been said that those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it. What this saw fails to mention is that history often gets worse with repetition.