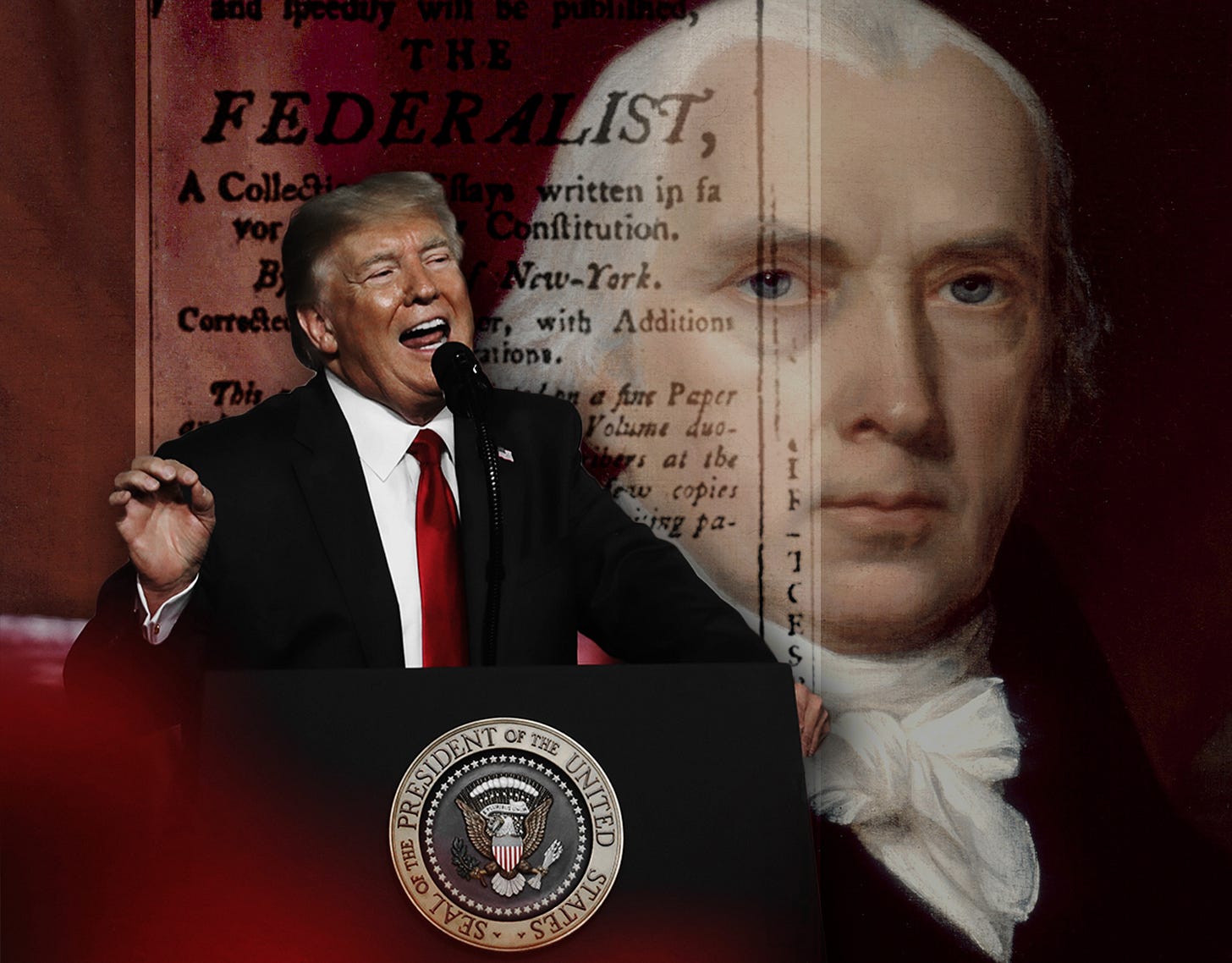

Federalism vs. Trumpism

The president has flopped and flailed. The governors have stepped up.

One unanticipated side effect of President Trump’s actions in office has been a years-long, force-fed civics lesson on the meaning of the constitutional separation of powers. Now, his words and deeds during the coronavirus crisis are putting another important constitutional concept on center stage: federalism.

But while Senate Republicans unabashedly abandoned their oaths to uphold the Constitution by failing to seriously consider the impeachment charges against Trump, state governors from both sides of the aisle are choosing the people over politics—demonstrating the benefits of federalism and proving that ethics and principle still exist in American politics.

The term “federalism,” like “separation of powers,” does not explicitly appear in the text of the Constitution. It represents the compact that the states made in surrendering a portion of their sovereignty to a central authority, the federal (i.e., national) government. They did it by ratifying the Constitution in 1788, and by constitutional amendment 27 times since.

In the words of James Madison in Federalist No. 51, the principle of federalism also operates so that each government—state and national—serves as a “sentinel” of the other in protection of individual liberties:

In the compound republic of America, the power surrendered by the people is first divided between two distinct governments, and then the portion allotted to each subdivided among distinct and separate departments. Hence a double security arises to the rights of the people. The different governments will control each other, at the same time that each will be controlled by itself.

The Constitution contains competing provisions that come into play when federal and state powers clash: the Commerce Clause and the Necessary and Proper Clauses of Article I on the one hand, which together give the federal government broad power in certain circumstances, and the 10th Amendment, which reserves any residual powers not given to the federal government to the states, on the other. That residual power includes the so-called police power, which is the source of the various stay-at-home, travel-restriction, and business-interruption orders issued by states to reduce widespread COVID-19 illness and death.

Historically, much of the federal-state conflict centered on slavery and then civil rights, with the federal government often in the posture of enforcing the Constitution against recalcitrant states. Southern delegates to the Constitutional Convention invoked federalism to protect slave interests. Much later, after the Civil War, the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the Constitution abolished slavery, provided equal protection of the laws to everyone, including formerly enslaved people, and gave formerly enslaved men the right to vote. The Supreme Court later interpreted the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment to apply to the states most of the provisions of the first eight amendments in the Bill of Rights. Just last week, the Court held that states must abide by criminal defendants’ 6th Amendment right to a unanimous jury verdict in Ramos v. Louisiana.

Federalism was again advanced for purposes of preserving segregation and discrimination in the South during the civil rights era of the 1950s and 1960s, culminating in the landmark Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education. It deemed segregation in public education unconstitutional while at the same time confirming that “education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments.”

By the same token, the Supreme Court has relied on federalism principles to strike down efforts by the national government to remedy segregation in public schools, deny relief to individuals who allegedly suffered discriminatory mistreatment by police, and outright reject a range of cases alleging unconstitutional state conduct, among other things.

Federalism’s push-and-pull between national authority and state autonomy thus remains one of the greatest tensions in American politics.

In his tortured dance with state governors over responsibility for crafting and implementing a coherent, humane, and effective COVID-19 response, President Trump has put the tension between the national government and the state governments in bold relief. But this time around, it’s the states that are coming to the rescue of the people. And they are doing it regardless of Trump’s bullying politics.

Trump’s incoherence on federalism has become infamous. He recently claimed “total” authority over the states while directing them to deal with the virus on their own. And he has refused to fully invoke the federal government’s statutory powers to address a national pandemic while chiding governors for imposing social distancing and other restrictions that epidemiologists believe are crucial to public health. And he directed a trio of “LIBERATE” tweets at Michigan, Minnesota, and Virginia—all states headed by Democratic governors.

But unlike in the U.S. Congress, where Republicans are now happy to follow Donald Trump in walking across any coals, jumping off any bridge, and leaping off any cliff, Republican governors have faced off against Trump in the name of public health. Maryland governor Larry Hogan, with his wife as translator, recently negotiated and secured the purchase of 500,000 test kits from South Korea—a practical fix to the feds’ unresponsiveness. When Trump claimed that Hogan “could’ve saved a lot of money” by simply calling Vice President Mike Pence for help, Hogan—a Republican—retorted, “We did what [Trump] told us to do which was go out and get our testing.”

And when, in March, Mike DeWine, the Republican governor of Ohio, was asked about Trump’s Twitter refrain that “THE CURE CANNOT BE WORSE (by far) THAN THE PROBLEM!” he responded: “We’ve got to do it in the right order. When people are dying, when people don’t feel safe, this economy is not coming back. . . . . We have to do everything we can to separate ourselves from others.”

Now several states are forming “pacts” to coordinate reopening—fulfilling a role that would typically be expected from a federal response in an emergency—while others are “flying blind” to invite public contact amidst criticism that reopening without robust testing and contract tracing defies science.

Since much of the size and scope of today’s federal government, including the massive regulatory state that is so derided by conservatives, was born of the New Deal, federalism has long been associated with conservative values. Conservatives have for decades argued that much of the national government’s power should be devolved, the better to facilitate local self-government, citizen participation, and innovation.

Yet during a national pandemic, a strong case for a national response can be made. Representative Francis Rooney (R-Florida) made that case last week for The Hill:

We need the president to intervene, like Presidents Truman and Kennedy did with the steel companies, to ensure that production and distribution [of ventilators and personal protective equipment] is taking place in a timely manner. . . . The administration can also utilize trained federal employees, military and civilian, to provide much needed relief for our overworked front-line workers. . . . [A]nd perhaps most importantly, the president must assemble, and Congress should fund, research and development to find a cure.

But with Donald Trump at the helm, this is a time to thank the heavens for federalism. If the national government lacked the counterbalance of state governors poised to act, it’s beyond comprehension what havoc Trump would wreak.