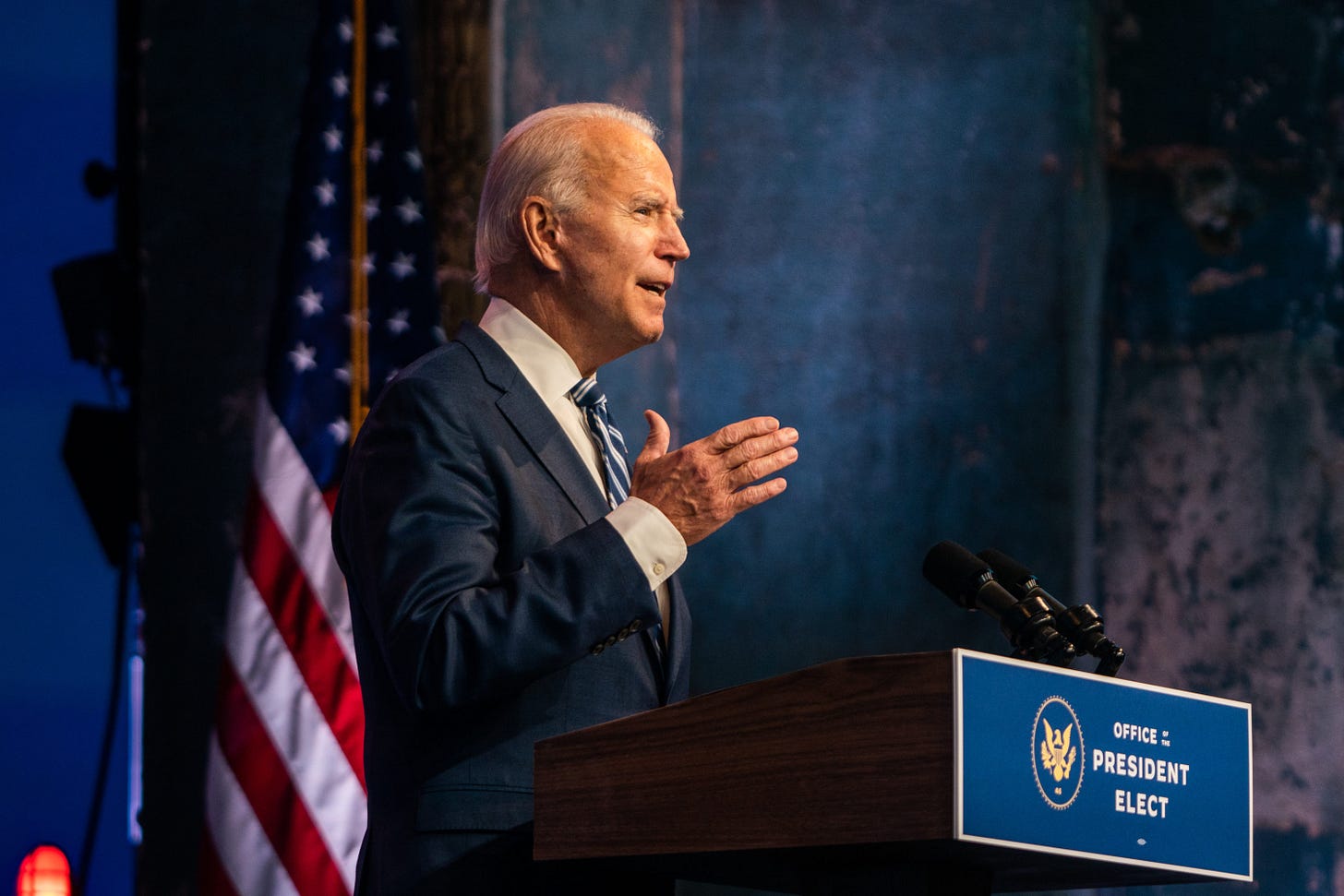

Five Foreign Policy “Don’ts” for President Biden

Avoiding the temptation to revive old ideas.

The world is a different place than when Joe Biden left the vice president’s residence at Number One Observatory Circle four years ago, let alone when he entered it twelve years ago. Some priorities and problems of those times are now irrelevant, and many of those that remain relevant face different circumstances. Ideas that a few years ago might have seemed wise, or at least defensible, now no longer suit today’s challenges. When Biden moves into 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue in nine weeks, there are old policies and ways of thinking that he should avoid.

The following five proposals offer what might be called a “not to do” list for the new administration.

1. Don’t pursue Israeli-Palestinian peace talks.

Every U.S. administration since Reagan has tried and failed to reach a peace deal between Israelis and Palestinians. That’s quite a track record: Six presidents who failed, each with different styles and preferences. It will be tempting for President Biden, as it was for his predecessors, to think he could be the one man who finally brokers peace.

But the current circumstances are incompatible with peace between the Israelis and Palestinians. Consider the obstacles to a peace deal, starting with the fact that each side is simply unwilling to make compromises the other demands. Both sides, for instance, want full control of Jerusalem for nationalist and religious reasons, and the only thing worse than not controlling the holy city for them is if the other side controls it.

There are more problems, too. Palestinian leaders are beneficiaries of the current circumstances. A peace deal that gives Palestinians sovereignty and takes the conflict out of the equation is a threat to their power. For decades, they have justified their autocratic rule on the grounds that the “emergency” situation demands it. Mahmoud Abbas is about to complete the fifteenth year of his four-year term. A true Palestinian state would also mean that Palestinian leaders would have to be held accountable for their incompetence, no longer having the Israelis to blame for their people’s problems. And then there are the financial considerations. Abbas’s predecessor, Yasser Arafat, died a billionaire. Abbas has a net worth above $100 million. Ending the conflict would mean a slowing down in the foreign aid that has enriched Palestinian leaders.

Besides, at 85, Abbas simply does not have much interest, flexibility, or political capital—and all of his likeliest successors will be even more hardline, so in the unlikely event that Abbas were to negotiate an agreement in good faith, they would presumably do their best to sabotage it as they are awaiting Abbas’s death so they can become the new leader.

Biden won’t be able to make history in this area during his own term, but he can help set the stage for one of his successors to do so. He should have a plan to build a civil society in the West Bank and push Hamas out of power in the Gaza Strip. A peace deal will be more tenable once Palestinians are no longer indoctrinated to hate their Jewish neighbors and blame them for all of their problems. This is not the work of four or eight years; it is a generational undertaking. But such a plan under a Biden administration would mark the first time that a U.S. president would be investing in a peace that is not hopeless from the beginning. Such a plan would require vigorous investment in the West Bank, and intensive verification to ensure that the strategy is working. It would require promoting a Palestinian government that is capable of managing the affairs of its people competently and is responsible and accountable to their needs and demands. It would require investing in liberal education in Palestinian areas and fighting corruption. And it would require promoting and protecting figures like Salam Fayyad, the widely respected and internationally trained economist and politician who was briefly the Palestinian Authority’s prime minister.

These kinds of conditions can help lead to a lasting peace—and a far-sighted but not unrealistic Biden administration can help establish them. To paraphrase one of Ronald Reagan’s favorite lines: There is no limit to what Biden can achieve in Israeli-Palestinian peace if he does not mind who gets the credit.

2. Don’t reach an agreement with Iran that doesn’t include human rights as a centerpiece.

Joe Biden campaigned on returning to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action—the deal negotiated between Iran and the United States, United Kingdom, China, France, Russia, Germany, and representatives of the EU. It was a key outcome of the Obama administration, and one that the former vice president was proud to be associated with. Biden’s national security adviser at the time, Jake Sullivan, helped lead the talks and remains close to Biden today. Of the frontrunners to be the secretary of state, two—Tony Blinken and Bill Burns—were directly involved with the talks. A third, Susan Rice, was a national security principal when the agreement was reached and involved with the talks and implications. A fourth, Chris Coons, was a supporter of the deal in the Senate. So naturally there will be inevitable temptations to revive the deal, which quickly began to die when President Trump withdrew from it.

But resuscitating the Iran deal is unlikely to succeed. One of its arms embargoes has already expired. And the agreement includes sunset clauses for enrichment embargoes—a compromise the negotiators made with a cross-that-bridge-when-they-get-to-it mindset, reasoning that maybe the regime would collapse before the embargoes ran out. But one of those embargoes will expire in 2026, which means that Biden will be nearing that bridge as his term is ending. Besides, Iran is already in breach of the agreement, even though it remains a party to it. In sum, the world has moved on, and the circumstances are different than they were when the United States left the treaty.

There is more to the equation. Iran’s hostile actions in the Middle East have increased since the agreement, including its use of proxies against U.S. forces in Iraq. And—most importantly—Iran’s regime has never been more vulnerable at home. U.S. sanctions have inflicted real pain on the Iranian economy, but the Iranian people no longer buy the regime’s propaganda that the primary driver of their problems is external. They increasingly blame the regime for the sanctions, as shown in the two mass protests in the past three years, both of which the regime brutally stifled.

The Biden administration, rather than trying to bring back the old deal, should try to reach a new agreement with Iran—one that addresses today’s questions, using the enormous leverage that the United States has. That new agreement should of course address Iran’s nuclear ambitions and regional aggressions, but it should also include human rights clauses. Iran’s violation of human rights has always been grotesque, but it has gotten even worse in the years since Biden left the vice presidency. Joe Biden campaigned on a foreign policy platform of championing democracy and human rights. He should live up to that promise by pushing hard for human rights in Iran, where political freedom in Iran is all but nonexistent; the number of political prisoners is increasing and the regime’s treatment of them is getting worse; and ethnic, religious, and sexual minorities have all faced crackdowns.

3. Don’t neglect Latin America and Africa as sites of competition with China and Russia.

For too long, the United States has ignored the importance of Latin America and Africa. In the new era of great power competition, we can no longer afford to make that mistake.

China has been aggressively investing in Africa through diplomacy and foreign aid to get access to the continent’s human and natural resources. Chinese foreign aid to Africa has surpassed America’s level. This is while Africa is an increasingly attractive replacement for China as a part of America’s supply chain. In fact, Africa is so attractive for manufacturing that China itself is moving factories there.

(Chris Coons, who, as mentioned above, is a contender for secretary of state in the new administration, serves on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee’s subcommittee on Africa, and formerly was its chairman. Susan Rice, another contender, is an Africa expert and the former assistant secretary of state for African affairs.)

As for Latin America, this week marks the seventh anniversary of when then-Secretary of State John Kerry declared the Monroe Doctrine “over.” He was wrong then and even more obviously wrong today. China and Russia are trying to increase their military ties in Latin America. Russia, China, and Iran have all been providing support to the Maduro regime in Venezuela and maintaining their close ties with the Cuban regime. China has also been buying influence in Latin America through foreign aid as America has been increasingly neglecting the region. The last thing America needs is Sinophile governments in its own neighborhood. A Latin American tour by the secretary of state—or better yet, the president himself—will be a good signal that America is back.

4. Don’t give up on Iraq’s democracy.

The Iraq War seemed like an early success, then turned into a catastrophe, was redeemed by a strategy shift (the “surge”), only for the United States to depart and leave the country to Iranian wolves. And while U.S. public opinion about the war’s start remains very divided—not once since 2006 has Gallup’s tracking poll shown fewer than 50 percent of respondents calling the war a “mistake”—there doesn’t seem to be much division when it comes to interest and patience today: Americans are just over Iraq.

But just because Americans are not interested in Iraq doesn’t mean that Iraq is not interested in them. The United States is oil-self-sufficient, but our allies are not, and Iraq is the world’s sixth-biggest producer of oil. As a Biden administration is almost certain to try to contain Russia, the United States will need to protect oil-rich countries, including Iraq.

America’s interest in Iraq goes beyond energy, however. As with Latin America and Africa, the Middle East is a site of great power competition. China wants to increase its influence in the region. The Russian military is back in the region, too—for the first time since Egypt kicked it out a half century ago. And America needs to keep the region from tipping away decisively from the liberal world. Especially with the Russian military in Syria and the forthcoming Sino-Iranian agreement that will allow China to have a military base in Iran, the United States needs a pro-U.S. Iraq to balance China and Russia.

And for the first time in many years, there is a ray of hope. Last year’s protests in Iraq finally produced some positive results. Combined with the killing of the Iranian general, Qassem Soleimani, Iran is now fighting for its life in Iraq. The Iraqi people rightly blame Iran for their political dysfunction, and they want Iran out. News coverage of the pandemic drowned out some good political tidings from Iraq this year: Mustafa al-Kadhimi’s ascension to power in May. The new Iraqi prime minister is anti-Iran, and the pro-Iran factions strongly objected to his appointment. He has done a decent job of overseeing reform so far, but he is just an interim prime minister, and he has promised to hold parliamentary elections next June. As conditions in Iraq are finally starting to look promising, the Biden administration must avoid any suggestion—even rhetorical—of walking away from Iraq. Instead, President Biden should come out in support of Kadhimi and his reform agenda as the right man to bring a new and better era to Iraq.

5. Don’t renew the New START without including all Russian nuclear arms.

The New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) was another signature achievement of the Obama administration. The treaty limits the deployment of Russian and American high-yield (“strategic”) nuclear weapons. Conservatives objected to the treaty back in 2010-11, but it was ratified by the Senate with a bipartisan vote.

The real problem with the treaty has always been not what it included but what it left out. Vladimir Putin has been trying to overcome its financial inferiority to NATO by undertaking low-cost strategies. One of these low-cost strategies has been developing low-yield (“nonstrategic”) nuclear weapons. The current Russian stockpile of low-yield nukes is superior to those of the United States and NATO members combined. This gives Russia “escalation dominance” in Europe against NATO—that is, the ability to escalate the violence of a conflict to a level at which it has clear dominance.

New START is due to expire in February 2021, and Vladimir Putin has already expressed interest in renewing it for another five years, which is an option under the agreement. There will be a temptation to simply renew this signature outcome of the Obama administration, one that several senior actors of the new Biden administration were involved in achieving—but that temptation should be resisted: One should always be suspicious in doing anything Vladimir Putin is interested in. The incoming administration should consider renewing the treaty only under the condition of putting a limit on all of Russia’s nuclear weapons, not just the high-yield ones.