Five Projects Trying to Bridge Our Civic Divides

And why there is a gap between how we judge ourselves and how we judge others.

In the 1990s, the polymathic economist Timur Kuran—then at the University of Southern California, now at Duke—coined the term “preference falsification” to describe a “specific form of lying”: “the act of misrepresenting one’s genuine wants under perceived social pressures.” Preference falsification is perfectly normal; Kuran started his book Private Truths, Public Lies with an account of a fictional dinner party in which a guest might lie about liking the décor just to be polite, or might obscure his real thoughts about subjects of conversation to get along with the other guests. However well intentioned, preference falsification can have negative consequences, including distorting views and degrading discourse, thereby undermining social trust and the capacity to work for the common good. At a large scale, it arguably plays a significant role in today’s societal dysfunction, contributing to a mismatch between our opinions and our perceptions of others’ opinions. Thanks to the Massachusetts-based think tank Populace, we have some recent data that can help us understand how preference falsification affects Americans’ collective illusions and shared beliefs. In mid-2019 and early 2021, Populace undertook two national surveys, both designed to simulate real-world decisions by forcing respondents to make tradeoffs that distinguish between personal opinion and perceived societal opinion. This survey design reduces both the “ceiling effect” (whereby respondents claim everything is important) and “social desirability effects” (in which respondents say what they think the questioner wants to hear). In what follows, I describe each of the Populace surveys, then use their findings to provide a context for some ambitious efforts to rebuild the bonds of social trust—highlighting five projects that could help to overcome the dysfunction associated with preference falsification in America’s communities.

Americans Talk About Success

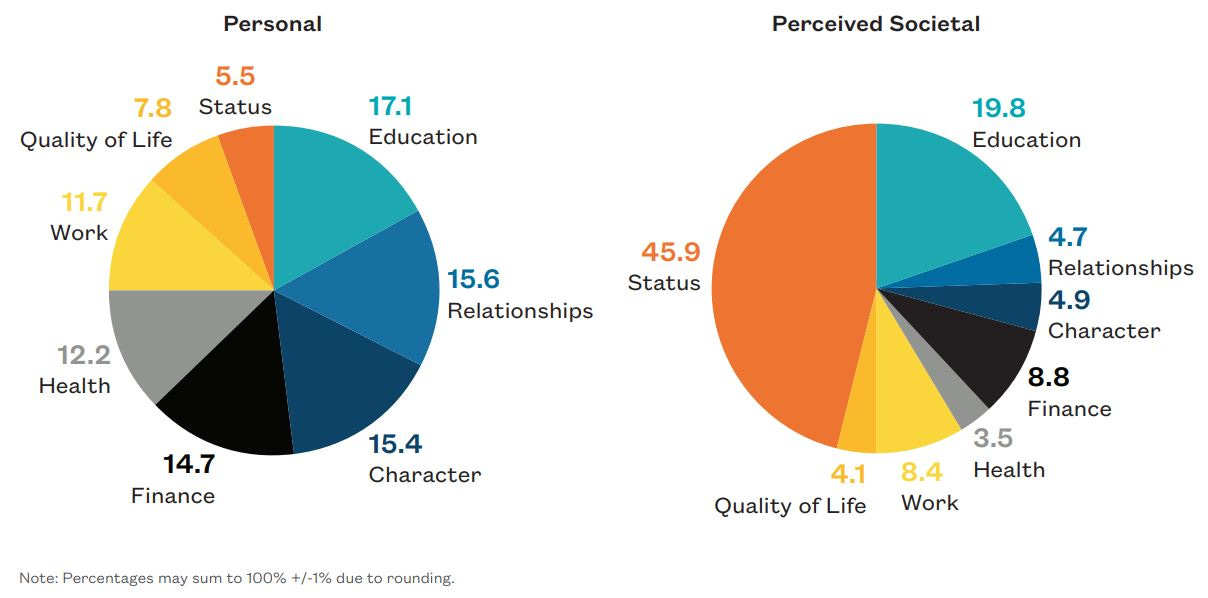

The Success Index analyzes how Americans define a successful life. Developed by Populace with Gallup and conducted in July 2019, it involves interviews and a nationally representative survey of 5,242 adults, with the results weighted demographically. Questions covered 76 attributes divided into 8 domains: education, relationships, character, finances, health, work, quality of life, and status. Two “success pies” emerged representing how people defined success for themselves and how they believe others define it:

Total Composition of Success, By Percentage of Eight Domains

(Courtesy of Populace) Two important findings emerge. First, many Americans perceive societal success (the pie on the right) in status terms, although status is nearly irrelevant to how they judge their own personal success (the pie on the left). Almost half (45.9 percent) rank status as the most important factor in perceived societal success, with education (19.8 percent) and finances (8.8 percent) far behind. But when it comes to personal success, the most important domains are more evenly distributed across education (17.1 percent), relationships (15.6 percent), and character (15.4 percent), with status last (5.5 percent). Second, the divergence between the “personal” and the “perceived social” definitions of success is even greater than the pie charts above suggest. Americans think about their own success in complicated ways, but believe that others think about success more simplistically. The poll respondents rated 5 attributes—being famous, having an advanced degree, being a graduate of an elite school, owning a business, and having a large social media following (an answer that skewed toward younger respondents)—as sufficient to account for more than half of how success is defined by others. But the diversity of opinion about what constitutes success for oneself means that it takes 21 attributes to reach the same threshold. Only one attribute is on both top-5 lists: Possessing an advanced degree is something we deem important for ourselves and we believe others consider important. But fame, elite schooling, and having a big social media following are all at or near the bottom of the list of attributes by which we judge our own success. Parenting is the top attribute contributing to personal success, followed by a high school diploma/GED and being trustworthy. So individual Americans typically don’t subscribe to the perceived societal view of success based on status, manifest in attributes like wealth, power, and fame. We judge our own success in terms of what’s done together, manifest in education, relationships, and character. It is displayed in attributes like graduating from high school, community involvement, regularly seeing family, having at least two close friends, parenting, and being considerate and trustworthy. This suggests that most Americans have a view of personal success grounded in social capital—emphasizing relationships and the networks and institutions that nurture and multiply relationships across larger groups and communities—and connected to the virtues that foster social capital, like integrity, hard work, and empathy.

Americans Talk About Aspirations

The other poll from Populace is the Aspiration Index—a survey of how self-described Biden and Trump voters view the country’s future, developed from individual interviews conducted in December 2020 and a nationally representative survey of 2,010 adults conducted in late January 2021. Both groups agree on several high-level goals for the nation. Out of the 55 goals offered as options by the pollsters, there were 9 that both Trump and Biden voters prioritized highly enough to list among their top 15. The highest-ranked goal among all Americans is an overwhelming commitment to the nation being one in which “people have individual rights (e.g., free speech, peaceful assembly, to keep and bear arms, freedom of religion).” That goal is also the top priority that respondents believe “most people” want to protect for future generations. Both Biden and Trump voters express urgency on 5 policy goals:

access to quality health care;

safety in communities and neighborhoods;

criminal justice reforms;

help for the middle class; and

modernized infrastructure.

At least 50 percent of both groups would be “upset” without significant progress on these issues over the next few years, true across almost all races, genders, education levels, and generations. The most partisan issue is immigration. For Trump voters, the goal of seeing that the nation “severely restricts immigration” ranked 3rd out of 55, versus 46th for Biden voters. Trump voters’ personal views also stressed the goal of having “secure national borders,” putting it 2nd out of 55, versus 31st for Biden voters. In looking at the areas of overlap between the two voting blocs, both say they want equal treatment and opportunity but not necessarily equal outcomes. Goals ranked toward the top include not just people “hav[ing] individual rights” but also having a nation in which:

“people are treated equally—regardless of background—in all aspects of society” (6th overall);

“people are able to go as far in life as their abilities and aspirations will take them” (12th overall); and

“people treat one another with respect” (14th overall).

On the other hand, an America that “has very little economic inequality” was 41st overall (29th for Biden voters, 51st for Trump voters). So Biden and Trump voters hold collective illusions about each other. What is mistaken for vast partisan disagreement is instead intense but narrow differences on limited issues within a context that values equal treatment and opportunity rather than equal results.

Collective Illusions and Societal Dysfunction

Kuran explains that preference falsification has negative social and political consequences because it misrepresents public opinion, warps civic conversation, and hampers communities’ capacity to change for the better, often preserving widely disliked structures. When conditions regulating public expression shift and genuine individual preferences become known, there can be a quick, even massive, recalibration of public sentiment. He provides examples, including why the rapid fall of communism caught even the most astute experts by surprise, developing a “threshold sequence”—a statistical model popularized in the terms “domino effect” and “tipping point.” As preference falsification is unmasked and true preferences emerge, the change threshold grows so that “cumulative change [becomes] a latent bandwagon” creating an unexpected and sharp growth in public sentiment for change. This raises a provocative question: Is it possible that organizations and projects of moderate size, by exposing our preference falsification for what it is, can have an outsized effect in improving our nation’s political and civic life?

Five Projects Worth Watching

As it happens, there are several organizations working to engage individuals in community conversations and activities to bridge the gap between personal opinion and perceived societal opinion, aiming to unleash a threshold response by inviting participants to see that they have more in common than assumed. Some organizations are international with U.S. affiliates; some national with local partner organizations; and some state-based or local. They use specific processes and tools to guide discussions that restore civility and tolerance to civic conversations. (Full disclosure: Some of the organizations mentioned here receive financial support from the Walton Family Foundation, where I am a senior advisor.) More in Common works internationally, launching in 2018 its U.S. Hidden Tribes Project that surveyed a nationally representative sample of 8,000 individuals, including 30 one-hour interviews and six focus groups. It identified seven population segments—“tribes”—with diverse viewpoints on issues. Eliminating the left and right political ends of the continuum, the remaining five groups of nearly two-thirds respondents create an “exhausted majority,” fatigued by polarization and eager to talk about “how we got here and . . . move forward.” More in Common works with local organizations, conducting community forums and focus groups, and using other tools to reduce polarization and solve community problems. The Better Arguments Project, a collaboration of several groups including the Aspen Institute, has this as its guiding maxim: “Americans don’t need reconciliation. They need to get better at arguing.” Training includes best practices for better arguing organized into three categories: understanding historical context, exercising emotional intelligence, and recognizing power dynamics in relationships. Braver Angels (formerly called Better Angels) endeavors to overcome political polarization, understood to include not only disagreement but personal contempt and distrust. Restoring civic trust must be rooted in local communities creating patriotic empathy, or “love of country . . . shown by our concern for our fellow citizens.” Its program uses skills training, debates, and other workshops to create Better Angels Alliances, local community groups that meet regularly to debate and discuss today’s issues. Training includes learning how to talk across disagreements in an empathic way, strategies for engaging in political conversation with peers without demonizing each other, and how to talk about politics with loved ones to bring families closer together. Programming includes corporate groups and college debates. The Woodson Center works primarily in low-income communities on poverty and social justice issues, especially crime and youth violence. Teaming up with local youth-serving agencies, it organizes and facilitates conversations with individuals often in violent conflict. Through dialogue and other assistance, including education and social and financial support, the center trains peer mentors and youth advisers to create violence-free zones. The center also has an affiliate network and a fellows program. The Indianapolis-based Sagamore Institute focuses on “heartland” issues and local citizenship and includes a community financial investment program called “Commonwealth” that entails “performance philanthropy.” It convenes diverse community members for discussions, offering education, technical assistance, and training, including financial services that expand economic opportunity. It works to overcome divisions by increasing minority entrepreneurship and improving second-chance employment for formerly incarcerated individuals. Commonwealth is an equity or debt investor in eight private companies and an operating partner in eight nonprofit organizations.

Trust and Community

Writing in the New York Times last year, Yuval Levin described the dysfunction that engulfs many Americans and their institutions—a condition rooted in a missing “structure of social life: a way to give shape, purpose, concrete meaning and identity to the things we do together.” He points to the need to “rebuild the bonds of trust essential for a free society.” A prime reason for this dysfunction is preference falsification. The organizations listed above are unobtrusively working to overcome the ways that preference falsification can undermine social trust. It is still too early to judge whether their efforts will result in citizens coming together to work for the common good—but it is not too early to hope.