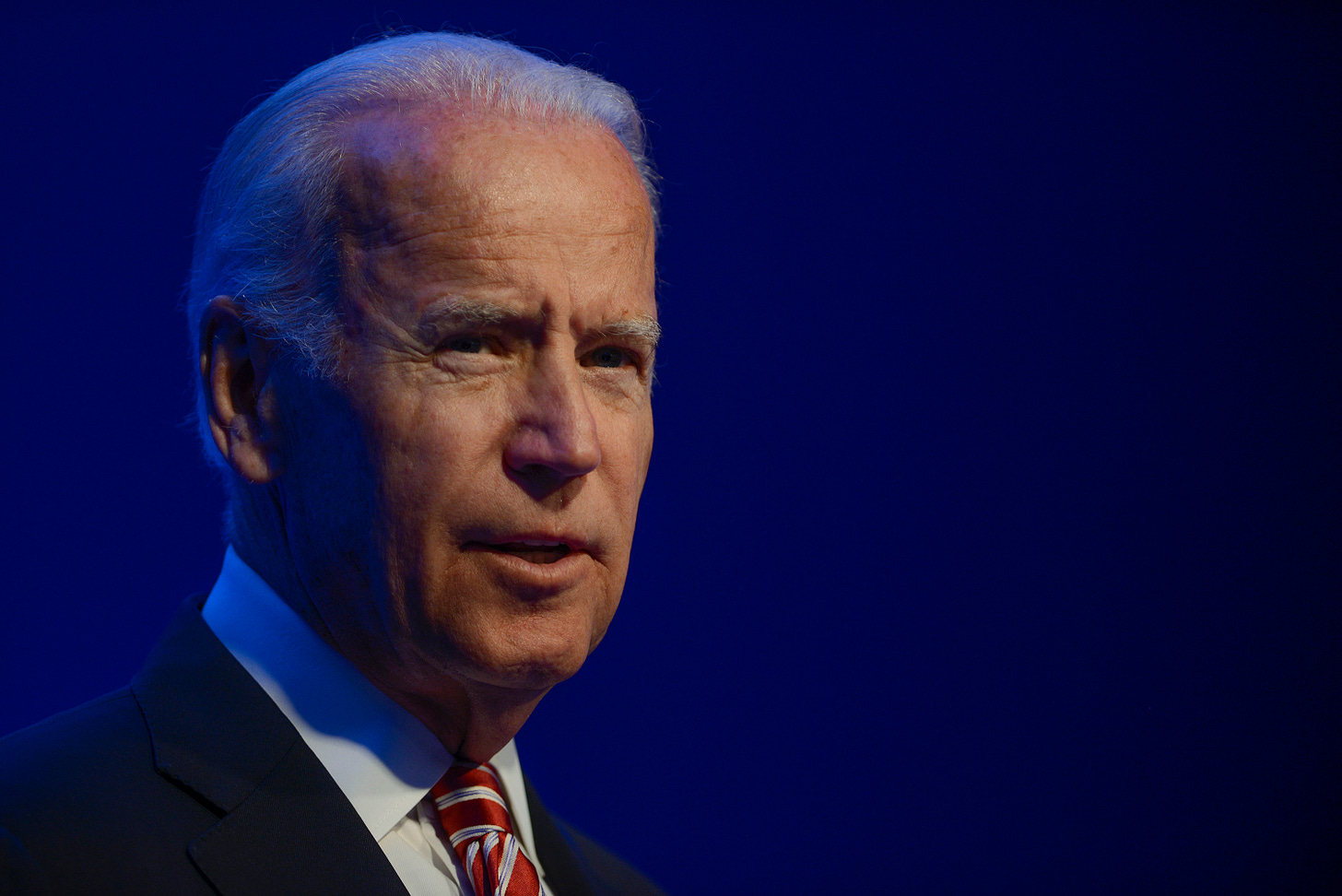

For the Democrats, It's Biden—Or Chaos

It's the damnedest thing: After a year wherein his campaign too often evoked Weekend at Bernie's, a close look at the primary map augurs that Joe Biden will be the Democratic nominee.

For all his endemic flaws, sentient Democrats should hope so. Extensive road testing of his rivals suggests that the alternative is chaos—or, more likely, defeat.

Writing in the Wall Street Journal, Karl Rove—a superior political mind, and no slouch as an historian—makes a credible case for chaos in its most rarefied form: a contested convention "featuring back-room deals and horse trades that anger and fracture the party." In short, bliss for reporters. And Trump.

The tributaries of Rove's riveting train wreck are, for the most part, the Democrats' own doing. New delegate allocation rules promote a fractured field: instead of winner-take-all, any candidate who garners 15 percent in a state will receive a proportional share of delegates. Further, a frontloaded calendar means that nearly 40 percent of all delegates will be chosen by Super Tuesday on March 3—a scant month after the Iowa caucus—and a full 69 percent will be chosen by the end of March. These conditions, Rove argues, assure that more candidates will stay in the race while preventing any one from building a prohibitive lead.

Other factors inform Rove's dystopian analysis. Current polls show four candidates with considerable support, and two others with some potential to break through. This raises the prospect of a political Lord of the Flies wherein candidates cross-cannibalize each others' support without creating a runaway winner. At the convention, super-delegates—party officials chosen by right and likely to favor establishment candidates—can no longer vote until the second ballot. And what if they then thwart the first-ballot leader, unleashing the party's boundless capacity for outrage and mutual recrimination?

As melodrama, this is enthralling; as electoral politics, it's Russian roulette. And so, a message of hope for those who prefer sanity to four more years of Trump: Joe Biden is your salvation.

Of necessity, Rove's scenario incorporates the current national polls—snapshots in time which cannot anticipate the fluid dynamics in key primaries. That said, for the last year Biden's lead has been relatively stable, confirming that he attracts the broadest and most consistent support—if not frenzied enthusiasm—of Democratic voters. By comparison, Warren and Sanders have swapped places over time; and while Buttigieg is looming larger in Iowa and New Hampshire—both disproportionately white—he lags among the more diversified electorates which dominate subsequent states.

All four front runners—two progressives and two relative moderates—have grave limitations. For all but Biden, the question is whether their floor is perilously close to their ceiling.

Polling suggests that the progressives, widely assumed to be ascendant, still represent a minority of the primary electorate. Moreover, as a matter of demographics Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders appeal to somewhat differing constituencies. Warren's following includes economically and educationally upscale Democrats—potentially more susceptible to poaching by their sociological peer, Pete Buttigieg. Sanders appeals more to young people and the less educated, but perhaps more committed, blue-collar voters. To challenge Biden, one of the two progressives must first consolidate these groups, thereby eviscerating the other.

The party's more traditional liberals and moderates—who still predominate—are largely drawn from minorities, suburbanites, ethnic voters, and a slice of middle- and working-class folks. They are Biden's natural constituency. Some of their elements, especially white moderates, are being contested by Buttigieg and, potentially, the dogged Amy Klobuchar and the self-funded Mike Bloomberg. But Warren and Sanders have also targeted the minorities so essential to Biden; in particular, Sanders has made inroads among Hispanics.

Sharpening fights over issues such as healthcare and reliance on big donors could further polarize the early primary electorate. Healthcare may dent Warren and Sanders, while controversy over funding sources may damage Biden and Buttigieg. But other strategic calculations transcend ideological differences, potentially wounding all but Biden in unpredictable ways.

Reluctant to attack each other, Sanders and Warren have focused on the newly-minted Wall Street Pete, he of the wine cave and McKinsey pedigree. Buttigieg, in turn, rightly concluded that the way to peel away Biden’s support among moderates was not by attacking Biden, but by savaging Warren on healthcare. In the demographic jumble, this had a further benefit: because they are widely perceived as the brains of the bunch, Warren and Buttigieg, more than Sanders, have some cross-ideological appeal among upscale Democrats. Indeed, Warren had hoped to expand her base by appealing to this slice of the primary electorate.

But she and Buttigieg are, of course, are quite different. Warren has tried to position herself through detailed policies; Buttigieg has positioned himself by well, positioning. But he did Warren real damage by using healthcare to wrap her around Sanders' ideological axel.

Thus far all this maneuvering has left Biden’s coalition largely intact. One remembers the Republican primaries of 2016, where Trump's challengers savaged each other in order to emerge as the alternative, perceiving too late that this self-created abattoir had beheaded them all. Among Biden's challengers, one sees the same devolutionary dynamic.

In many ways, the fulcrum of this predation is Mayor Pete. He accelerated the infighting by going after Warren. In the last debate, the other also-rans pummeled his inexperience and small-bore electoral success. Plainly, his rivals don't like him—he's the smart kid all the others love to hate.

Some of this may be anger at his precipitous rise, or simple envy of his gifts. He's gotten this far because he's preternaturally poised, persuasive, articulate, and quick on his feet, blessed with near-perfect political pitch. He may be a once-in-a decade political talent. But his hallmarks also include ideological flexibility, an avoidance of clearly articulated positions, and the considerable skills as a political assassin he turned on Warren—all of which have earned him the enmity of many fervent progressives.

Moreover his ceiling is as apparent as his promise. Stylistically, he's a classic white meritocrat who appeals most to older members of his own class and least to working people, minorities, and the young. His weightiest millstone is the aversion of black voters. He stumbled when dealing with the African-American community in South Bend and despite all his skills, he seems to have a limited facility for addressing racial concerns. As a married gay man, he unnerves socially-conservative blacks. As he labors to overcome these problems, his support among minorities remains minuscule.

Collectively, these deficits seem like too much to overcome. Should a Democrat win in November, mark Buttigieg down for secretary of HUD.

Still, you can hardly blame Buttigieg for noticing that Warren's biggest liability is Bernie Sanders.

To contend for the nomination Warren must convert a swath of Sanders voters and satisfy the rest. And so, fatally, she decided to throw in with Sanders' single-payer proposal until Mayor Pete compelled her to detail her own: a complex proposal which provoked so many doubts and questions that, as an interim measure, she was forced to advance a more gradualist approach to ending private healthcare coverage—a retreat that satisfies neither moderates nor progressives.

Equally damaging, her embrace of single-payer tarred her other ambitious proposals with the rubric of "big government." Warren now occupies the worst of both worlds: insufficiently pure for the most ardent progressives and too ideological for previously persuadable moderates who admired her specificity and conviction.

Her poll numbers have plummeted; her fundraising followed. After threatening to marginalize Sanders, she now trails him decisively in both. Among the oddities of this campaign is to see Warren snagged in a de facto pincer movement on healthcare between polar opposites, Mayor Pete and Bernie.

Another oddity suggests the persistence of sexism: Warren’s pugilistic promises to "fight" the forces of plutocracy provokes a blowback about stridency that Sanders' jeremiads don't. While one can fairly question the mass appeal of high-decibel rhetoric in a nation wearied by Trump, the insidious folkways constraining female candidates endure.

While writing Warren off has proven perilous, in the moment Sanders seems hardier. Over time he has acquired a certain kind of likability: call him a "happy curmudgeon." He may be the only septuagenarian politician ever to be energized by a heart attack—his doctors credibly insist that he's fine, and even his opponents privately acknowledge that he looks great.

Because he is bracingly consistent—indeed, unchanging—Sanders has a strong and unwavering base of voters who double as a perpetual ATM: He raised a staggering $34.5 million in the fourth quarter of 2019. The wildly popular (among progressives) AOC loves him, which gives his campaign fresh verve among a motivated segment of the young. Schooled by his failure in 2016, he has made strides with some minority voters. Given all that, and because he doesn't give a damn about the Democratic party—of which he is not a member—Sanders will no doubt be in the race until the end.

For Sanders and his fervent base, it is likely to be a bitter end. His ceiling is called socialism, which remains an alien concept among the electorate writ large. His call for a "political revolution" places more faith in centralized government than most Americans can muster. Pragmatic voters fear that he can't win; moderates fear that he will. He retains the stentorian style of an Old Testament prophet which some find off-putting. He is ready-made to endure—and in the end fall short.

And so, there is Biden.

Joe Biden’s shortcomings are manifest. He arouses barely modest fervor; his base of supporters skews older. As Paul Waldman puts it, "Joe Biden is the candidate of Other People"—those supposedly persuadable independents and Republicans who pragmatists believe he alone can reach. For party loyalists he's a nostalgic figure, burnished by Barack Obama, a status which obscures the self-inflicted wounds which doomed his two prior presidential runs.

But for Biden, more than Sanders, his vintage unsettles, and his propensity for misadventure endures. Age has seasoned him but not, it seems, sharpened his political reflexes. His debate performances leave supporters dreading that there is a trapdoor beneath his podium that will be triggered by some bewildering lapsus linguae. For Biden supporters, “winning” a debate means the feeling of relief at a steady performance. All too often, his personal and political judgment flags—the most dire example of which is Hunter Biden.

From every perspective, Biden's youngest son was the centerpiece of House impeachment proceedings. No doubt Trump's efforts to tar Hunter and his father with criminal conduct are odious and scurrilous—as were the Republicans’ cynical slanders about both. But Biden's failure to curtail his son's blatant peddling of putative influence in Ukraine, and Hunter's lack of any legitimate qualifications for outsized payoffs from a shady Ukrainian company, splashed them with the same swamp water in which Trump bathes. What's fair doesn't matter: Biden's political malpractice weakens Democrats where they should be strong, reminding voters of all they loathe about Washington's culture of corruption.

Even more stupefying was Biden's inexcusable statement that he would not honor a GOP subpoena to testify in a Senate impeachment trial. Anyone not comatose knows that Trump's refusal to allow testimony by key subordinates is the basis for an article of impeachment; that Mitch McConnell's refusal to allow such witnesses has caused Nancy Pelosi to withhold the articles from the Senate; and that Biden's own refusal fulfilled Trump's fondest fantasies for a propaganda payoff.

Belatedly informed that he had put a gun to his own party's head, Biden reversed course. But this shocking lapse raises serious questions: What in God's name was Biden thinking? Does he listen to advisors? If so, what did they tell him? And all of this underscores his potential for self-immolation.

And yet, like a 77-year-old Terminator, Biden keeps on coming. So it is well to consider all the reasons that Democrats of sounder judgement should pray for his survival.

Take the looming elephant in the Democrats' room: that paramount perennial, the economy. Uniformly, Democrats point out that its benefits bypass millions of Americans. In particular, Sanders and Warren decry the accumulation of economic and political power which prefigures plutocracy. All of this is true, and needs saying.

But for now, most macro-economic indicators seem strong and many Americans are grateful: a recent CNN poll shows that 76 percent believe that economic conditions are "somewhat" or "very" good. This is most problematic for Sanders and Warren, whose economic messages are pitched to transformative populism.

Whatever the merits of that position, as long as most voters feel reasonably optimistic, it is ill-advised to stake the presidency on persuading them they're wrong. This places a premium on stressing other issues where Democrats can strike electoral pay dirt—depending on how they're framed.

Start with healthcare, the second most salient issue for most Americans. Here Trump's performance has been politically brain-dead: He campaigned on repealing Obamacare, which would raise the cost of healthcare, menace those with pre-existing conditions, allow states to restrict access to Medicare, and deny millions of Americans reasonable access to basic care. All Democrats need do is counter with programs which provide the most security to most Americans—including the many millions satisfied with their private health insurance.

A recent New York Times poll shows that 58 percent of Democrats favor making a government-run healthcare program available to all who want it, while allowing people the choice of keeping their private insurance—just as Buttigieg and Biden propose. Only 25 percent preferred the Sanders/Warren single-payer plan which eliminates private insurance.

Again: It's foolish to tell voters that they're wrong. Even among Democrats, single-payer is sinking Warren. The only way Democrats lose on this issue is by promising to eliminate private health insurance because that’s what flies on Twitter.

Another key issue, providing affordable college, is also there for the Democrats’ plucking.

Roughly two-thirds of Democrats favor plans to make college more affordable, or public colleges free for middle- and lower-income Americans. Less than one-third favor free college for all, which is the Sanders-Warren proposal.

The reasons vary. Some voters worry about the cost; others object to educating wealthy kids at taxpayer expense. Both groups can live with Biden.

But perhaps the biggest issue favoring Democrats transcends policy or politics-as-normal: Voters are repelled by a president with feral behavior, boundless divisiveness, contempt for norms, relentless self-absorption, and an infinite need for attention. They long for stability, dignity, predictability, and national cohesion. Most of all, they want a decent man or woman they can like and trust.

And that's Uncle Joe, the garrulous old guy whose generosity of spirit keeps fractious family Thanksgivings from going off the rails.

The explicit premise on Biden’s campaign is restoring America to dignity and unity. So is the idea of Biden as human healer realistic? Truthfully, no. Our deeper problem is not Trump, but us—our widening political polarization and social alienation.

Remember when Barack Obama was going to deliver us from those polarizing Clintons? Before Inauguration Day, Mitch McConnell was promising to sink him. Obamacare passed without a single Republican vote—despite the soothing presence of Joe Biden. Trump's special contribution to society was his idea to make cementing our tribal hatreds not an unfortunate byproduct, but the actual raison d'etre of his presidency.

Still, if ridding America of Trump is the Democrats' prime imperative, it will surely help for Americans not immersed in the acid bath of reality to hope that Biden can deliver us from ourselves. It's a worthy aspiration and, as Ernest Hemingway wrote: "Isn't it pretty to think so."

So that’s why Biden should win the nomination; a close study of the primary map tells one why he very well might.

True, none of the candidates have a clear lane to the nomination; all flag among some critical element of the Democratic coalition. But for all save Biden, it appears, this will ultimately prove fatal.

Even the four early contests in February—Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada, and South Carolina—promise to yield more losers than winners. Historically, the first two have created a slingshot effect and winning both has often translated into winning it all. But nothing, it seems, can dislodge Biden among the minority-majority Democrats of South Carolina.

To build momentum, Warren has banked on winning Iowa and New Hampshire, hardly sure things. For Warren and Sanders, Iowa and New Hampshire pose a potential cage match between progressives. Trends favor Sanders. By early March, Warren could become a political science case study: How a smart and spirited contender can be undone by a strategic judgment which, given the ideological premise of her candidacy, was devilishly difficult to avoid.

Buttigieg, too, is focused on Iowa and New Hampshire. Given that both states are disproportionally white, he could win or place. But his weakness among minorities will almost surely stymie him in Nevada and doom him in South Carolina.

Nevada is stronger in union membership than the first two states, and also has more minorities: it's over 6 percent African-American and 29 percent Hispanic. That makes it promising for Sanders, Biden, and, potentially, Warren. As for Buttigieg, his demographic limitations spell also-ran.

Then comes South Carolina, whose predominantly black primary electorate is accented by Hispanics. Biden polls at 44 percent among African-Americans; Sanders, in second-place, trails him by 30 percent. Buttigieg is sitting at roughly 0.0 percent. By month's end, Buttigieg could become the most gifted roadkill in the race.

For Sanders, Iowa and New Hampshire offer the prospect of marginalizing Warren, or Buttigieg, or perhaps both. Then he should surpass Warren in Nevada and finish second in South Carolina. But while that is happening in February for Sanders, Biden will see at least two of his three principal challengers face a grim reckoning: as for the dark horses, Bloomberg cannot buy it, and Klobuchar is not built to survive it.

Then comes the harrowing gauntlet of March. By the end of that month—proportional allocation notwithstanding—the Democratic nominee may seem foreordained.

As noted, as of Super Tuesday on March 3, almost 40 percent of the delegates will have been claimed. The biggest hauls are in California (nearly 40 percent Hispanic and 6 percent black); North Carolina (22 percent black and over 9 percent Hispanic); Texas (11 percent black, and almost 39 percent Hispanic); and Virginia (20 percent black and 9 percent Hispanic). As for white voters in these states—excepting, perhaps, California—most hew toward the center. And Super Tuesday is also salted with smaller, but demographically similar, states: Alabama, Arkansas, Colorado, and Tennessee.

This pivotal day is ready-made for the candidate with whom minorities and moderates feel the most comfort: Joe Biden. As the New York Times notes: "Historically, black Democratic primary voters have tended to back a single candidate, helping thrust the voting block to the forefront in Southern states where black voters make the majority of the Democratic electorate. If a single candidate can get huge vote margins with black Democrats, like Barack Obama did in 2008 and Hillary Clinton did in 2016, he or she can amass a big delegate lead over other candidates."

This history favors Biden. Further, Biden should be competitive among Hispanics, who dominate Texas and California. And if the alternative is Sanders or Warren, white moderates will likely break for him in overwhelming numbers, too.

The rest of March should solidify his lead. By its end, almost 70 percent of first-ballot delegates will be accounted for and nothing about the remaining contests seems prohibitively problematic for Biden: Most of the big prizes—Michigan, Florida, Illinois, Ohio, Georgia—appear hospitable to his pitch.

Other factors should ease his way down the stretch. Any remaining contenders (other than Sanders) will be pressured to drop out, whether because of concerns about money, or their futures, or the health of the party. That includes Bloomberg, who may damage Biden in California but not beneath the Mason-Dixon line.

Which leaves Bernie Sanders, sustained by his imperishable base of financial and electoral support and a resentment of the party establishment shared by his most devoted followers. Biden would have to stumble dramatically—some epic mistake; a sudden health problem too serious to ignore—for Sanders to overtake him.

But the nightmare prospect for Democrats seems more likely: a Biden-Bernie showdown which reprises the corrosiveness of Clinton versus Sanders. And there are already intimations that Sanders is eager to go to war against Biden.

As in 2016, Sanders claims to be the most electable. Most Democrats believe otherwise: Asked in a recent poll which candidates can beat Donald Trump, 77 percent named Biden; 60 percent said Sanders.

The head-to-head polling data agrees with this belief and so does the iron math of the Electoral College.

In 2020, Trump could lose the popular vote by several million, and still eke out a victory by carrying states Democrats lost narrowly in 2016: Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. To win them back, Democrats must squeeze out every available vote from suburbanites, working people, minorities, and independents. Biden simply has more strength among these groups, and his proposals arouse fewer misgivings.

Another path for Democrats goes through Trump-leaning states which could be flipped with greater minority turnout: North Carolina, Arizona, Florida, and, perhaps, Georgia. In that scenario, the optimal Democrat could reach moderate whites while appealing to Blacks and Hispanics. And again, that's Biden, not Sanders.

These battleground states also underscore the unusual importance of choosing the best vice-presidential nominee. For Biden, this is already critical: If victorious, he would be the oldest person ever elected president. But he also has a unique advantage in making the optimal choice. Because he is well-positioned in crucial Midwestern swing states, he has the most leeway to propitiate progressives and minorities while uniting the party by naming a co-star of color, most likely a woman.

One first thinks of Stacey Abrams, a politically talented and intellectually gifted powerhouse who could out turn out progressives and minorities and, with luck, put Georgia into play. But there are other prospects, as yet undiscussed.

Take, as one example, Congresswoman Val Demings of Florida, a smart and forceful presence during the House impeachment hearings. True, she's lightly-experienced in national politics. But on paper she's a strategist's dream: up from poverty; a former social worker; an ex-policewoman with a degree in criminology; a retired chief of the Orlando Police; and a mother of three with a 31-year marriage to a former policeman who is now the mayor of Orange County, Florida.

Without too much effort, one can imagine a rapturous Democratic convention as Biden reaches to a talented newcomer, making history with the obvious delight of a politician who is also, in the end, a very good man. That could be a moment.

To beat Donald Trump, the Democrats will need considerable acumen, some luck, a bit of magic—and, most of all, real enthusiasm and unity of purpose. With the right running mate, Joe Biden could win. He may be the only Democrat who can.