"Free College" Isn’t About Free College

This isn't about policy. It's virtue signaling. Stop it.

Over the weekend a minor fight erupted between the Warren/Sanders and Buttigieg camps over whether or not “free college” plans should be means-tested.

https://twitter.com/Lis_Smith/status/1200460822679564289

Judd Legum has a smart dissection of why means-testing isn’t really about means-testing. It’s about optics. In short:

Most of the children of “millionaires and billionaires” are going to elite private schools, not public colleges.

The administrative costs of means-testing are non-trivial.

Setting the bar at $100,000 in family income (Buttigieg’s plan) incentivizes all sorts of cheating.

It also means that families with high-school-age kids are going to have to be careful about not taking promotions.

Not mentioned by Legum: This also introduces a new layer of employment discrimination and downward wage pressure for jobs just above the $100k line. Let’s say you make $95k a year and your employer wants to promote you to a job that pays $110k a year. If you have a 16-year-old, the employer can lowball you to $99k. Which has the effect of pushing the wages down for that position for everyone.

I suspect Legum is right about all of this. But I also suspect that he doesn’t go far enough. It’s not just the discussion about means-testing that’s not really about means-testing.

The entire discussion about free college isn’t really about free college.

College is, as a sector, broken. This isn’t an opinion. It’s just a fact.

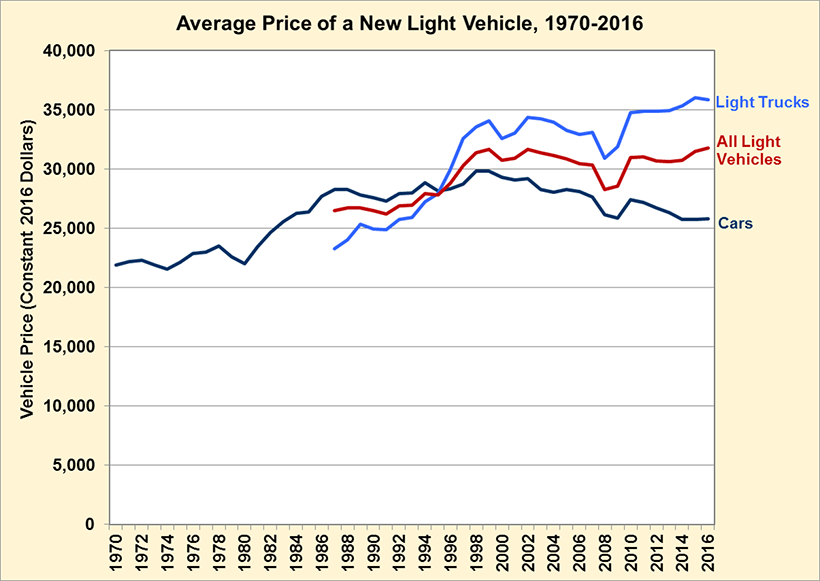

If you bought a car in 1985, you probably paid about $27,000 (that is, in 2016 dollars). If you bought a new car in 2016, you probably paid about $27,000 (also in 2016 dollars). In the intervening 30 years, the real price of cars moved around a bit, increasing and decreasing. And the average price for light trucks mostly increased. But not by all that much, relatively. Have a look:

Department of Energy

And over that period, the cars got a lot better. Cars in 2016 are more fuel-efficient, more reliable, less expensive to own in total cost, and much, much safer.

Now let’s do college. If you went to a public college in 1985, you paid about $8,000 a year (again, we’re using 2016 dollars). If you went to a public college in 2016, you paid about $17,000 a year. That’s a real-dollar increase of more than 100 percent.

And was your college degree “better” in 2016? Probably not. For one thing, it became more common. For another, over that period there was a proliferation of soft majors resulting in degrees that don’t really help you in the job market. I mean, have you been in a college classroom recently?

The best case you could make for a college degree getting “better” is that its lifetime wage utility compared to non-college wages has increased. That’s not nothing! But it’s also not really a transformative shift. And also, you can’t disentangle that increase from everything else that’s been going on in the economy.

To take just one for-instance: As a greater percentage of people go to college, the people left in the non-college end of the pool are disproportionately going to be the people at the low end of the wage and skill scale. So you’d expect that gap to grow just because of the self-selection that's happening.

So that’s one way that the college sector is broken. Another is that, like with healthcare, the final consumer costs for college are incredibly opaque.

When you go to the doctor and get a test, the doctor bills you some astronomical price, knowing that you aren’t going to pay it. Your insurance company will. And even then, the insurance company won’t pay the sticker price. It will pay some lower price that’s negotiated after the fact.

Well, most people aren’t paying sticker price for college, either. But like with health insurance, the mechanisms for loans and financial aid are so obscure that it’s almost impossible for consumers to get a true sense of what the real cost will be until after they’ve applied to the school. And worse: Because you have to re-apply for financial aid every year, you don’t know for sure what your four-year total cost will be. You only know the cost for one year at a time.

Imagine going to the doctor, getting told that you needed a series of four injections, and that they could only tell you the price of the next injection, not the four-injection total. Crazy, right? Well, that's how college pricing works.

Then there’s the admissions system and Operation Varsity Blues and a hundred other corruptions. Like the fact that colleges are “non-profits.” I went to Johns Hopkins which, in 2010, had nearly $10 billion in economic output in the state of Maryland and accounted—all on its own—for almost 4 percent of all wage-and-salary jobs in the entire state. Does that sound like what our historical understanding of non-profit status was meant to foster?

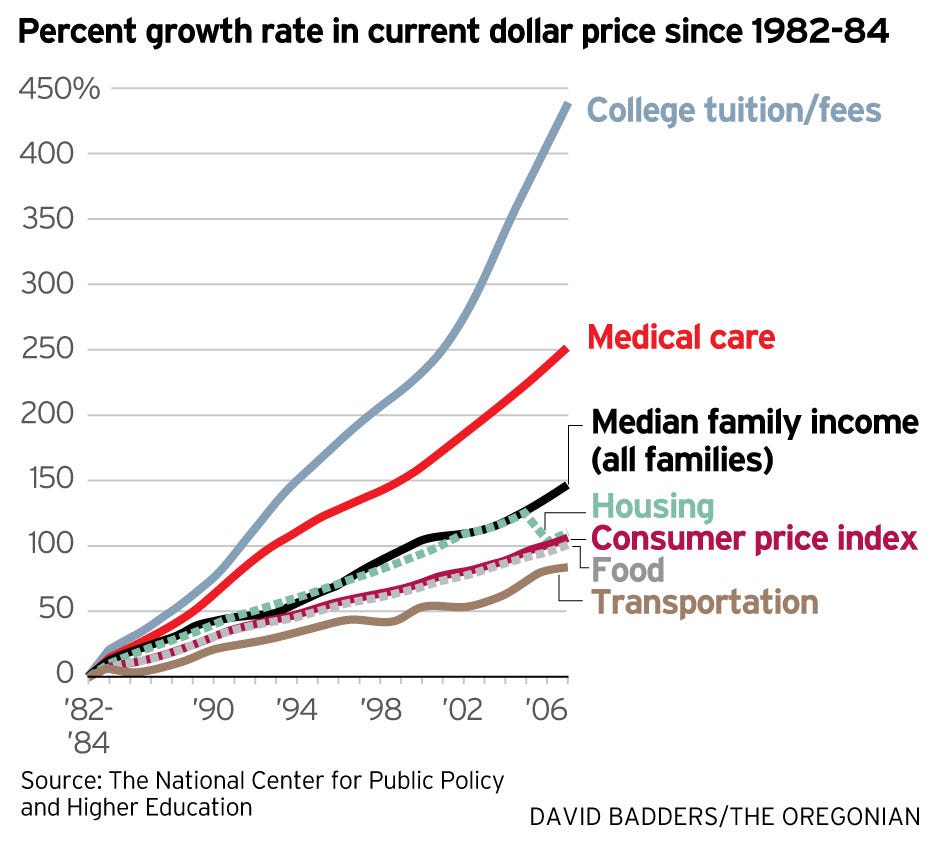

Seriously: The entire college system as it now exists is a failed sector where the market has been so thoroughly distorted by externalities that it pretty much cries out for reform. Just take a look at the curves on this non-inflation-adjusted graph:

It's crazy!

But why do we think that making college "free" is the reform we need to rationalize the sector?

There is one very good reason to make college free: Because we decide, as a society, that we want to encourage the education of the populace. And so just in the way that we made K-12 education a free public good, we’re going to expand that good by an additional four years to include college.

That’s a nice sentiment. Maybe it’s even a good idea. But there is no indication that making college free will fix the underlying irrationality in the industry.

Who is paying the colleges when college is free? How will those rates be negotiated? By the states? By the federal government?

How will colleges control costs? Who decides admissions requirements?

And why is it that we’ve all suddenly decided that making college “free” is better than, say, establishing a free federal online degree program that undercuts the existing price structure and forces the industry to rationalize itself? Or revoking tax-exempt status for university systems that look more like Microsoft than like the Little Sisters of the Poor?

I mean, I’m not going to tell you that those changes would be more effective than making college free. But it seems like these are open questions we ought to explore before we go making a wholesale revision to the system.

And what I will tell you is that “free college” is more of a signal than a policy. Because it’s the other half of forgiving student loan debt.

As a matter or practical politics, you can’t embark on a program to forgive student loan debt if you’re not also going to make college free. Why should the government bail out the people who just escaped from the college-industrial complex while leaving the next generation of parents and students to fend for itself?

And forgiving student loan debt is the real issue. Because student loan debt is three things: (1) a real burden for many Americans and, not coincidentally, many Democratic primary voters, who skew younger ; (2) an artifact of the broken college system; and (3) an effective piece of populist politics for a key Democratic constituency.

We’re not actually going to make college free any time soon, no matter who is the next president.

The next president, if a Democrat, is most likely to spend his or her initial political capital on healthcare expansion. Then maybe tax reform. If it’s Elizabeth Warren, maybe a wealth tax will come first. After that there will be fights on climate change or immigration reform. Free college will be so far down the list that it won’t be actionable even under the second term of a highly-successful Democratic president.

So it would be nice if, instead of making “free college” part of Democratic dogma now, the candidates and wonks used this time to figure out the best way to actually, you know, fix college. And getting into academic fights about whether and how to means-test a program that is still—at best—a decade away from being seriously considered is a recipe for getting locked into a policy proposal that might only help a little bit.

Or possibly even make things worse.