GOP Senators Support the ‘January Exception’

By voting to halt the impeachment trial, 44 Republicans showed they believe misdeeds in a president’s last weeks in office are unpunishable.

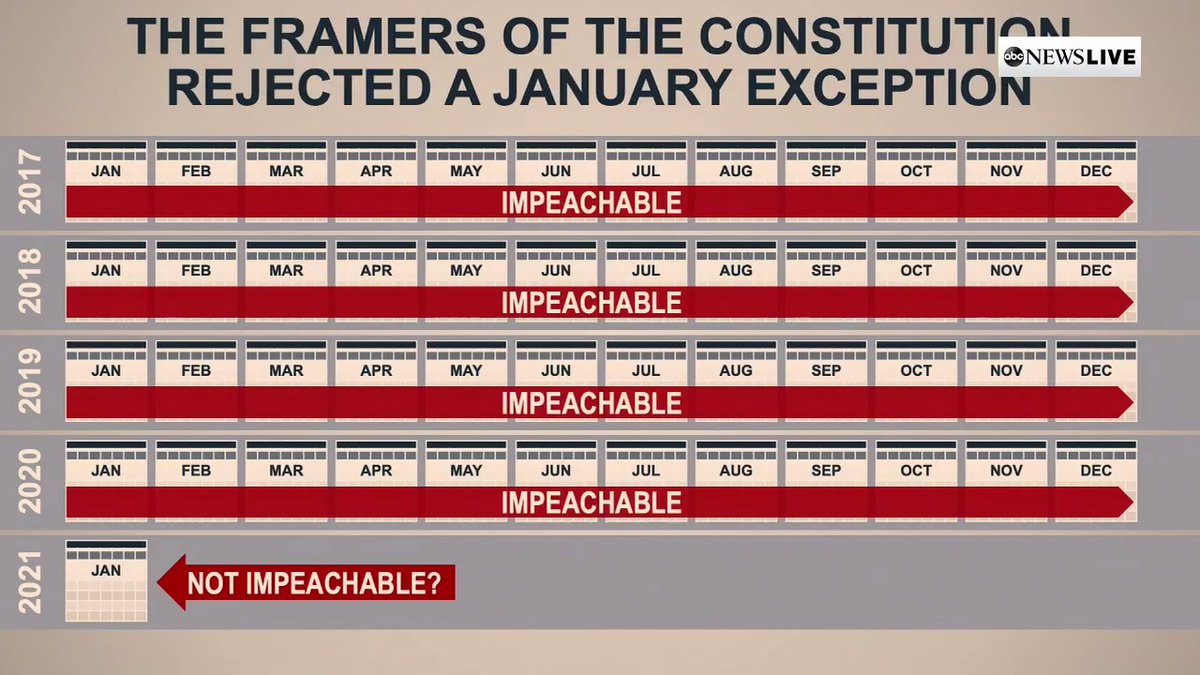

In their presentation on Tuesday, the House impeachment managers introduced the concept of the “January exception.” The idea is this: If the Senate had ruled that the second Trump impeachment trial is unconstitutional—either on January 26 when Sen. Rand Paul first formally raised the question, or on Tuesday when the Senate took up the question again—the implication would be that no former president could be held accountable via impeachment. That would mean that a president could, at any time, avoid an impeachment trial merely by resigning office, perhaps up to the minute before an impeachment trial gets underway.

Hence the “January exception”: Basically the entire month of January after an election would be a constitutional free-for-all, since it would be nearly impossible for an impeachment and trial for high crimes and misdemeanors committed after January 1 to begin and conclude before the expiration of the presidential term.

Trump’s defense team argued that even the current impeachment process, which is about to enter its second month, has been so speedy as to lack the “due process” necessary for impeachments. An even shorter impeachment and trial process, wrapped up within a month, would only compound that alleged offense. So, voilà, it’s impossible for the Senate to convict a former president for anything he did in his last month in office—at least according to the House managers’ construction of the Trump team’s arguments.

It’s worth making three brief points about the idea of the January exception.

First, in responding to the House managers, Trump’s lawyers asserted that even if a former president can’t be held accountable for his conduct by impeachment and Senate trial, he would still, as a private citizen, be subject to federal criminal law.

But this assertion is plainly wrong, in that it assumes that only crimes that a prosecutor could pursue in court are impeachable offenses. Certainly, there is some overlap between the category of impeachable offenses and the category of prosecutable criminal offenses. But it’s easy to think of examples of impeachable offenses that aren’t prosecutable crimes. If then-President Trump had promised the January 6 rallygoers that he would direct the federal government not to prosecute any of them for any offenses that day, that certainly would have been an (additional) impeachable offense. But because it involves a presidential power granted by the U.S. Constitution, it would not be a prosecutable action. It would be an impeachable offense, but not something a prosecutor could use to pursue criminal charges.

Second, even if the impeachable offense in question were also a federal crime, there remains a possible loophole—one that shows why it is so important to do away with the notion of a January exception. Remember how, during the lame-duck weeks of the Trump presidency, there was speculation about whether he could pardon himself? There remains considerable debate among constitutional scholars about whether self-pardons are constitutional. So say a hypothetical President Smith, a lame duck in his last weeks in office, commits a federal crime—such as inciting an insurrection or committing a murder on Pennsylvania Avenue. He then immediately pardons himself and resigns.

According to Trump’s lawyers, this hypothetical President Smith, now a private citizen, cannot be impeached and tried. And if self-pardoning is possible, he is not criminally liable, either. The combination of a self-pardon and a resignation would guarantee impunity. Without explicitly taking self-pardoning off the table, the Trump team’s argument amounts to not just a January exception but an anytime exception.

Third, and finally, you may wonder why this matters. After all, the Senate voted 56-44 not to adopt the Trump team’s arguments, so at least for now, a former president can still be tried even after leaving office, and this is essentially an academic debate, right? Well, not quite. The questions of whether a former president can be impeached after leaving office and whether a president can self-pardon remain open.

And, more importantly: Those 44 senators, all Republicans, who voted on Tuesday to stop the trial essentially all accept the January exception. Not a single one of them seems to have responded in public to that aspect of the House managers’ case. With their votes, they have shown that they believe a president cannot be held accountable by Congress for high crimes and misdemeanors during his final weeks in office.