How A Small Group of Senators Can Shape the Impeachment Trial and Vindicate the Constitutional Order

Should President Donald J. Trump be impeached by the House of Representatives? If he is, should he then be removed from office by the Senate? There's room for disagreement on both of these questions. But there should be room for agreement on the process by which Congress makes these decisions. Because we all have a stake in preserving a process that—going forward and whatever our disagreements about what's happened so far—is as fair and as constitutionally appropriate as possible.

We can do this. In the two previous impeachments of presidents that moved to a trial in the Senate, those of Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton, the trial was conducted in ways generally thought fair by both the critics and defenders of those presidents. Historians continue to debate the merits of the outcomes of those trials and of the strategies of House managers who prosecuted the cases. Which is as it should be. But in each case there was then and remains today a sense that the system was generally fair.

The key to the system working as it should is the understanding that the Senate as a court of impeachment is a different institution than the Senate as usual. When the Senate moves to become an impeachment court, senators take a new oath. At that moment the institution transforms itself.

That's why, according to Article I, section 3, clause 6 of the Constitution, senators, when sitting on a trial of impeachment, “shall be on Oath or Affirmation.” Of course, when elected to the Senate, all senators swear an oath to uphold the Constitution. But the senators, when sitting as a court, are asked to take an additional oath. It is a juror’s and judge’s oath—not a legislator’s oath.

Rule XXV of the Senate Rules in Impeachment Trials provides the text: “I solemnly swear (or affirm) that in all things appertaining to the trial of ____, now pending, I will do impartial justice according to the Constitution and laws, so help me God.”

And of course, for an impeachment trial of a president, the chief justice of the United States presides. He can be overruled by a majority vote of the other judges/jurors—which is to say, the senators. But the Constitution asks them to remember that they are not sitting as legislators, but now as judges and jurors. They are literally swearing to act in that spirit.

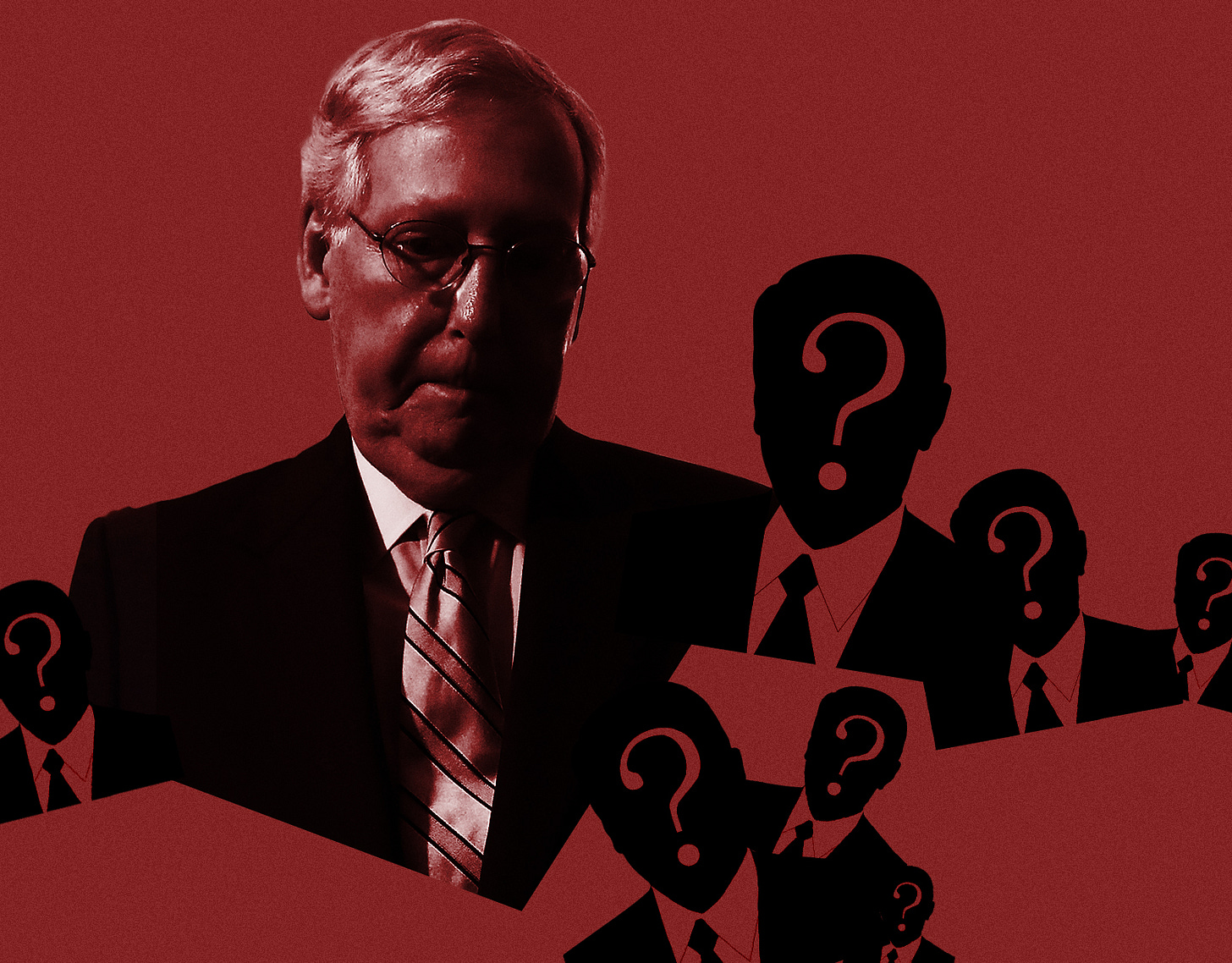

Most of us have a sense that an impeachment trial is different from Senate politics as usual. That's why there's been such a reaction to the fact of Senator Mitch McConnell comporting himself no differently on impeachment than he does when he’s whipping votes for a tax bill. McConnell hasn't merely publicly prejudged the outcome of the trial in which he will serve as a juror. He's announced that he intends to act during the trial in consort with the president and his lawyers, and to whip other senators on behalf of the president, as if they're mere legislators, rather than jurors who will soon swear to “do impartial justice according to the Constitution and laws,” so help them God.

But there is a way to avert this perversion of the duty of judging with which the Senate is entrusted. Before the trial begins—before the new oaths are administered—the Senate will adopt the standing rules for conducting the trial.

In this, Majority Leader McConnell has the responsibility to work with the Minority Leader to plan the conduct of the trial. In this role, the longstanding norm has been for the leaders to look forward to the trial, imagine the new institution, and craft a bi-partisan plan to insure a fair trial. In the Clinton trial, for example, the rules were negotiated by leaders of the two parties and were approved unanimously.

Senator McConnell has made no effort to consult with members of the minority—or even, as far as we can tell, with many of his own members—to ensure a fair trial. He has worked with the president's lawyers to attempt to prevent House managers from presenting their best case, while also attempting to make it possible that the president need not mount a real defense.

But this project to undermine the norms of the Senate as a high court of impeachment is not a fait accompli. Mitch McConnell may be the majority leader of the Senate, but senators are not sheep. Or at least if they are, it is only by their own choosing. If three or more Republican senators now join Democrats in insisting that the trial be structured to be the kind of full and fair trial anticipated by the Constitution and by the Senate Rules on Impeachment Trials, they can do a lot to make a fair trial happen.

A small number of responsible Republican senators—probably only three, in fact—could form a constitutional caucus. Or a small bipartisan group of senators could form such a group. They can determine what the outlines of a full and fair trial would look like. Surely this would include some number of witnesses on both sides, not all of whom need have testified in the House. Insisting on this should be easy, as it would be in accord with the wish of the House managers and the professed wishes of the president. The rules should err in general on the side of completeness and, of course, fairness.

This is the task that a small group of senators faces, and the opportunity they have: To ensure the Senate in which they have the honor to serve lives up to the high standards of our history and our constitutional order.

The awesome responsibility of an impeachment trial of a sitting president has fallen on very few senators over the course of American history. Most who have been put in this rare position found that a fair trial enabled them to win the respect of their constituents, even those who might disagree with the decision they rendered on the verdict.

Three senators can take a stand, enable the Senate as a whole to live up to its oaths, and force the parties to work together to make this a moment that demonstrates our constitutional order at its best rather than politics at its worst.