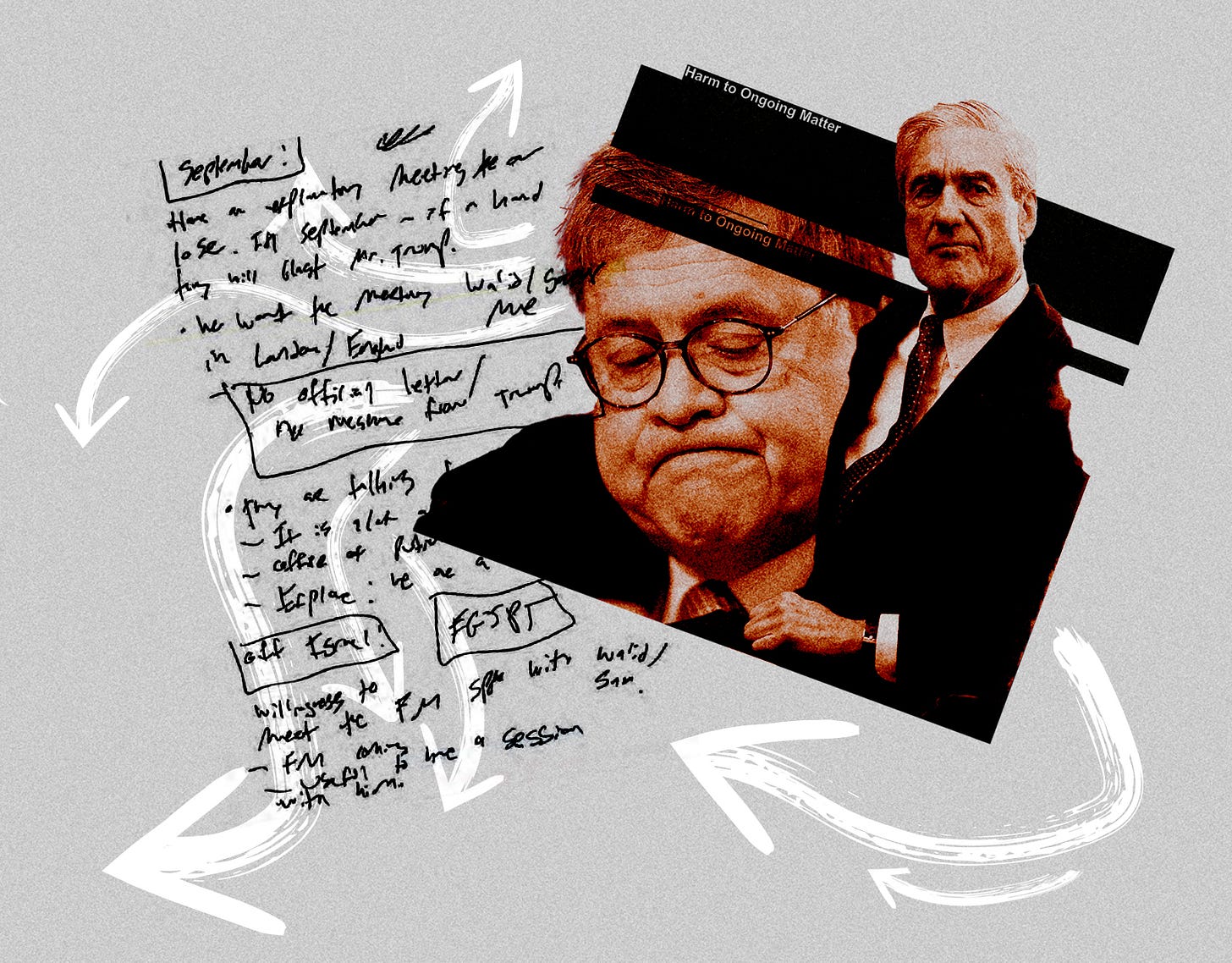

How Barr's Dizzying Attempt to Spin Failed

And what comes next for Barr, Mueller, and the report.

Last January, when Attorney General William Barr came before the Senate Judiciary Committee for his confirmation hearing, one question dominated the proceedings: Would Barr serve as an impartial and independent advocate for the rule of law—particularly with regard to special counsel Robert Mueller’s nearly completed investigation into Russian election meddling—or would he function as a political operative for his boss, the president? During those hearings, Barr was unequivocal: “I’m not going to do anything that I think is wrong and I’m not going to be bullied into doing anything that I think is wrong, by anyone. Whether it’s editorial boards or Congress or the president, I’m going to do what I think is right.”

At the time, many on the left viewed Barr’s claims with skepticism—partially because Trump had made no secret of his view that subservience was the preeminent quality he was looking for in his AG, and partially because Barr had written a memo the summer before telegraphing that he was skeptical of the possibility of Mueller recommending Trump be charged with obstruction of justice. But others argued—I was among them—that Barr was as good a candidate as we could hope to get from Trump: a highly qualified career official, and a friend of Mueller’s to boot. “In the current environment, the American people have to know that there are places in the government where the rule of law, not politics, holds sway,” he had said. “The Department of Justice must be such a place.” He had pledged his independence; he deserved the opportunity to exercise it.

Fast forward to Thursday morning, when Barr showed up for his scheduled press conference in advance of the release of the wildly hyped Mueller report. Democrats had protested that Barr ought not summarize the report’s conclusions prior to its release, but such press conferences are standard procedure for major Justice Department actions. It was the perfect opportunity for Barr to live up to the standard he had set for himself: To be the independent advocate for the rule of law by presenting a short, non-political summary of Mueller’s findings for those without the time or inclination to read the full thing.

That was not the Barr we got. The Barr who showed up was rather Barr the political actor, and the performance he gave was one worthy of his fellow mooks at the White House press office. Barr stuck to Trump’s approved talking points throughout: repeatedly parroting Trump’s claim that “there was no collusion” between the Trump campaign and Russia, and asserting that Trump had not committed any actionable act of obstruction of justice, on the grounds that Trump was understandably angry that some people thought he had colluded yet “took no act that in fact deprived the Special Counsel of the documents and witnesses necessary to complete his investigation.”

Not even an hour later, the redacted Mueller report was released, and showed just how hollow both halves of Barr’s argument were. Yes, Mueller said he had not found evidence that the Trump campaign had “colluded”—an imprecise term—with Russia’s election hacking efforts. But he did provide painstakingly detailed accounts of the Trump campaign’s attempts to coordinate with illegal Russian activity, such as this gem about former staffer George Papadopoulos:

In the first week of May 2016, Papadopoulos suggested to a representative of a foreign government that the Trump Campaign had received indications from the Russian government that it could assist the Campaign through the anonymous release of information damaging to candidate Clinton. Throughout that period of time and for several months thereafter, Papadopoulos worked with [Russia-connected, London-based professor Joseph] Mifsud and two Russian nationals to arrange a meeting between the Campaign and the Russian government. No meeting took place.

And no, Mueller did not recommend Trump be prosecuted for obstruction. But he did lay out a dizzying narrative of Trump’s attempts to stymie and frustrate the special prosecutor’s investigation—so much so that, as Mueller drily summarizes, “the president’s efforts to influence the investigation were mostly unsuccessful, but that is largely because the persons who surrounded the president declined to carry out orders or accede to his requests.” Mueller also states, contra Barr’s assurances, that Justice Department policy that a sitting president cannot be indicted played a substantial role in their decision not to indict for obstruction.

So was Barr lying? Not exactly—he was simply spinning the facts to fit as closely as possible into the simplistic and misleading narrative pre-approved by the president. You’d expect this from a garden-variety flack, but it’s deflating to see coming from the nation’s attorney general.

But the most important question at hand today isn’t “Is Barr a good guy.” The question is, “How should Barr’s willingness to shill for the administration color our view of the Mueller report?” And on that question, the answer isn’t as clear-cut as many of Barr’s skeptics seem to think.

For weeks now, critics of the administration have zeroed in on one particular damaging act Barr could carry out: As the man in charge of redacting the Mueller report, Barr theoretically had the authority to censor the parts most damaging to the White House. Perhaps the report as Mueller submitted it, the argument goes, is even worse for Trump than it currently looks.

But this fails to follow even if one argues that Barr is an unreliable narrator. Because Barr’s redacted version of the Mueller report will still face two accountability checks in the days ahead: a congressional review of a version of the report with all redactions removed save those concerning grand jury materials, and congressional testimony by Robert Mueller himself.

The congressional review, which has been sought by House Judiciary Committee chairman Rep. Jerrold Nadler among others, will be important. But it’s Mueller’s testimony that will really put the “Barr the unreliable redactor” theory to the test. The special counsel clearly cares about the results of his own investigation—he left a comfortable job in private practice to take its helm, and worked devotedly and doggedly on it despite a ludicrous public smear campaign for two years. The idea that he’d simply shrug and let a political actor defang its conclusions is practically inconceivable—yet that’s exactly what the redaction truthers have to believe.

There’s an important lesson for how Trump’s critics should handle the report in the days ahead.

The idea that the real dirt from the Trump-Russia scandal—the kompromat and prostitutes and secret trips to Prague is lurking just out of sight, around the corner, about to be revealed—is still with us today. If only we could get around Barr’s redactions—THEN we’d see the truth! Rather than focus on the alarming details we already know, professional speculators tell us the true goods are the ones yet to come. Take, for example, the vow by Nadler to subpoena the unredacted report, a vow he repeated today after the report was revealed.

Barr misconstrued much of the Mueller report on Thursday morning, and his ruse held up for less than an hour. If he tried to get away with any funny business on the redactions, we’ll know that soon enough too. After years of speculation, the Mueller report, such as it is, is here. Now is the time to focus on the ongoing scandal of Trump’s duplicity in the realm of the real. God knows there’s plenty to work with there.