How to Wage an Ideological Conflict with China

If the United States is to fend off the challenge from the Chinese Communist Party, it must recommit to its own ideals and values.

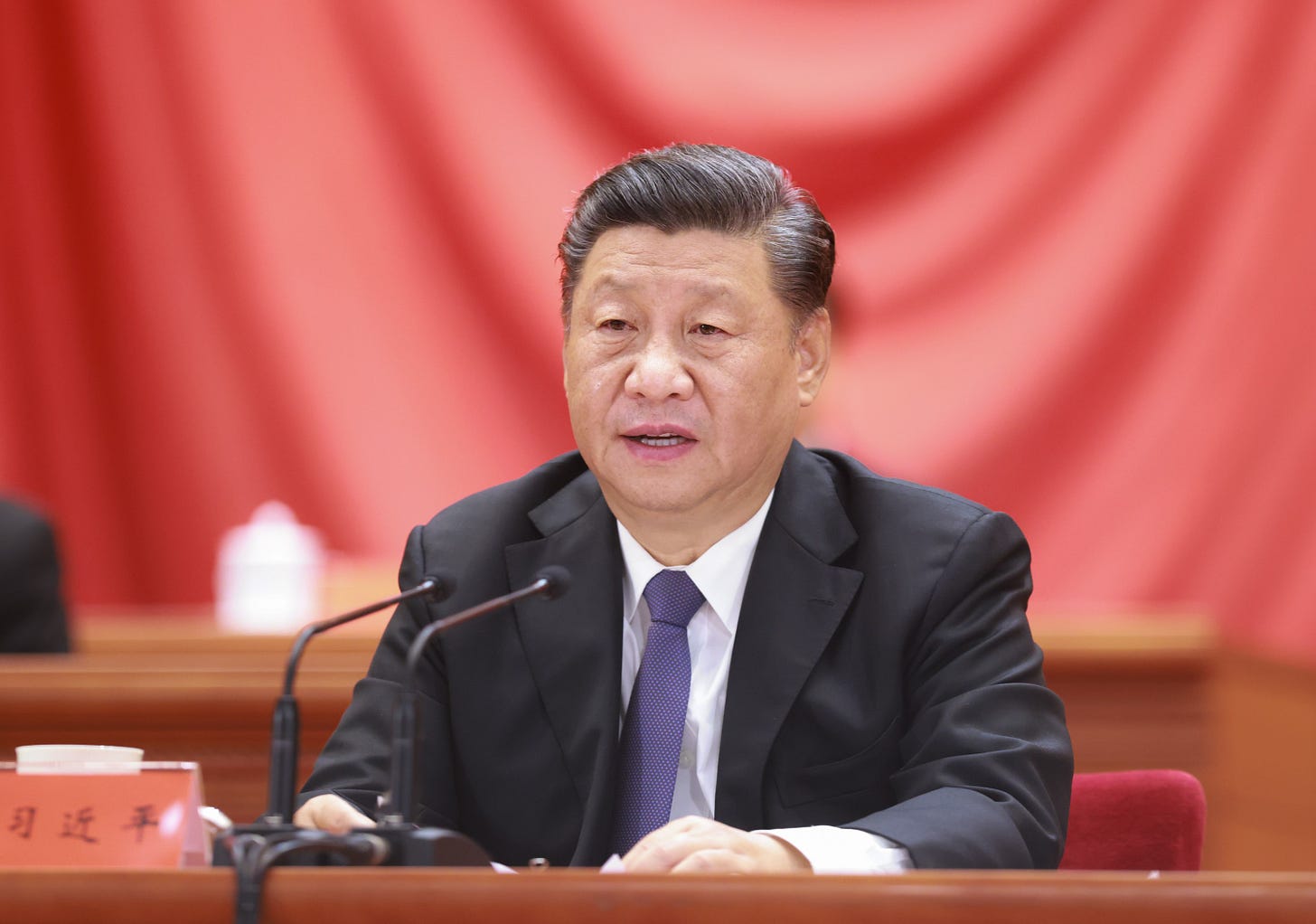

Both the Trump and Biden presidential campaigns vied to outdo the other in being “tough on China.” The Trump administration declassified an intelligence assessment that the Chinese Communist Party favored Biden over Trump, and Biden responded with harsh words for both President Trump and Chairman Xi. While the House and the Senate are slated to be sharply divided in the next Congress, there is broad consensus on the need to confront China. But consensus can be hazardous for strategy, and policymakers should be wary so that the rush to confront China doesn’t sacrifice America’s values and interests.

The key question for any strategy to compete with China is: With our economy closely tied to an authoritarian power, our channels of communication infiltrated by surveillance technology and weaponized information, and the legitimacy of our liberal institutions questioned from within and without, how can the United States avoid an outright military conflict and remain a free and open society? Any strategy to confront China by mimicking its illiberal tendencies would be self-defeating.

President Truman grasped a similar dilemma at the beginning of America’s confrontation with the Soviet Union. In a statement to Congress, Truman warned that failing to contain the Soviet Union would lead to the emergence of a “garrison state,” forcing the United States to “impose upon ourselves a system of centralized regimentation unlike anything we have ever known.” If the U.S. failed to build a network of allies to prevent the spread of communism, communism would gain strength and make the word unsafe for American democracy.

Truman’s successor, Eisenhower, though of a different political party, expanded on this warning. In his 1961 Farewell Address, Eisenhower cautioned the American people about doing too much in response to the Soviet threat: “Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry” can be responsible for ensuring that “security and liberty may prosper together.” Both presidents understood that the competition with the Soviet Union was not only military and economic, but also ideological and political. Sacrificing America’s democratic character would be unacceptable.

The words of the first two Cold War presidents are especially salient for our present moment as the U.S. confronts a new military, economic, ideological, and political competition with China. How much this emerging confrontation resembles the Cold War remains an academic debate, but a recent survey indicates that the American public views China as a significant threat to the United States.

While the great China debate rages on, Congress and the administration have begun to assemble a China strategy piece-by-piece. Congress has passed resolutions to investigate and sanction human rights violators in Hong Kong and Xinjiang. The president has issued executive orders to respond to legitimate national security threats posed by Chinese technological acquisitions. While overdue, both the next Congress and the next administration must learn from President George W. Bush’s laudable “Islam is Peace” speech at the Islamic Center of Washington, D.C., just 6 days after the 9/11 attacks: The first task in an ideological struggle is to defend against illiberal tendencies at home. So far, America’s elected leaders have ignored this lesson.

One critical example includes the worry that Chinese students studying in the United States pose an espionage risk. Sen. Tom Cotton even suggested that Chinese students should be banned from studying certain subjects at American universities. While Chinese intelligence has used Chinese-national students and scholars at American universities as assets, such a draconian measure would undermine American universities’ long-standing international reputation for being havens of opportunity, pluralism, and free exchange.

Such rhetoric also perpetuates a pernicious pattern of categorizing entire groups of Americans as threats to national security. While this tendency dates back at least as far as the Alien and Sedition Acts signed into law by President John Adams, the most egregious example is the internment of Japanese Americans, including many American citizens, during World War II. President Trump’s insistence on referring to COVID-19 as the “China virus” rekindled a similar hostility against Chinese Americans that dates back to the discriminatory Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

Today’s Chinese Americans face a dual threat of bigotry at home and tyranny from abroad. In addition to xenophobic attitudes encouraged by the White House, the coercion of the Chinese Communist Party aided by the long reach of digital technology and a robust network of informal agents—referred to as the United Front Work Department—also threatens Chinese immigrants to America and their families. The Chinese state has sanctioned American citizens and extortedChinese expats by threatening their relatives still in China. Any measure aiming to halt China’s extraterritorial intimidation tactics must pay special attention to the freedoms and well-being of Chinese Americans so as not to duplicate the oppression they face.

Ensuring that Chinese-Americans continue to be an advantage for the United States, instead of perceived enemies, is an urgent task for the Biden administration. But leading America into the competition that could define the 21st century requires much more.

The Biden administration will not only inherit a polarized country but also an ideologically polarized world. President-elect Biden recognized this in his essay in Foreign Affairs outlining his desire to restore American global leadership. Yet judging by the campaigns of his former rivals for the Democratic nomination, the rest of the party seems inclined toward retrenchment and more focused on domestic issues.

A Biden administration needs to unify both desires: restore confidence in American democracy at home and rebuild American credibility abroad. The two can be one in the same. After responding to the coronavirus, the first thing Biden and his allies in Congress should have on their agenda should be a list of reforms designed to reinvigorate American democratic government—not only for the health of the country, but as an example to other nations of the inherent flexibility and self-healing nature of democracy.

The first measure President Biden should pursue is a Presidential Accountability Act. Many voluntary measures such as releasing tax returns, divesting from personal investments, and selecting family members for government roles were taken for granted before Trump. These soft norms should be codified as statute by Congress.

Next, Biden should work with Congress to revitalize Congressional oversight. Public transparency is necessary (but not sufficient) to slow the avalanche of conspiracy theories rolling over American politics. Moreover, more muscular oversight ought to be only the start in a larger effort to reverse the trend of expanding executive power at the expense of the legislative branch. America has come close enough to Orbán-style authoritarianism to know now how to avoid it, and for our own sake and that of our allies with less consolidated democracies, we should demonstrate how to prevent the consolidation of power in a populist-nationalist executive.

Biden will also inherit a country still grappling with race and racism. Yet again, Truman provides an example of how a Biden administration can influence American politics at home to preserve what the president-elect has called the “power of [America’s] example” abroad. Truman’s Justice Department filed an amicus curiae brief before the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education, noting “Racial discrimination furnishes grist for the Communist propaganda mills, and it raises doubts even among friendly nations as to the intensity of our devotion to the democratic faith… [School segregation] jeopardizes the effective maintenance of our moral leadership of the free and democratic nations of the world.” As the United States continues to reckon with its past and present, the Biden administration should encourage other branches and levels of government to see every step against systemic racism as a victory against America’s adversaries.

The international community has rightly decried the detention of Uighur Muslims in China, yet the United States’s protestations are decried as hypocritical, coming from the country with the highest incarceration rate in the world. America’s incarceration problem is not the result of overt ethnic and religious oppression, and it lacks many of the most horrifying elements of the slow-motion ethnic cleansing in Xinjiang, but it remains a fundamental problem that is inconsistent with many of the same liberal ideas we stand for internationally. Because most prisoners in America are in state prisons, not federal ones, there is a limit to how much direct influence the Biden administration can have on this problem. But just as the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act Biden championed helped create the mass-incarceration problem, the Biden administration can wield federal influence to help alleviate it.

Human rights policy and democracy promotion are too often derided as trivial distractions within certain foreign policy circles. The Biden administration would be wise to align its mandate to reform liberal institutions at home with broader foreign policy goals necessary to succeed in a global ideological confrontation with China, Russia, and other authoritarian powers. Before we are able to be a shining light for the world, we need to reignite the flame of democracy here at home.