Impeachment and the ‘Due Process’ Canard

By treating the House impeachment inquiry as illegitimate, the president only risks creating new problems for himself.

In signaling his readiness for an impeachment trial, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell seems to have conceded the weakness of the Republicans’ primary procedural objections to the House impeachment inquiry—i.e., that the inquiry isn’t proceeding pursuant to a formal House vote. Nonetheless, it’s worth clearing the legal air here, particularly as the executive branch’s stonewalling of House subpoenas may end up in the federal courts.

As we’ve heard ad nauseam by now, impeachment is a political process—not a judicial one—and the Constitution itself contains scant detail regarding how the process must unfold, save for the requirements that the House has the “sole Power” to impeach for “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors”; that the Chief Justice of the United States presides over a trial in the Senate; and that conviction requires a two-thirds majority of the Senate “Members present.” The rest of the process is up to the majority parties in the respective houses of Congress.

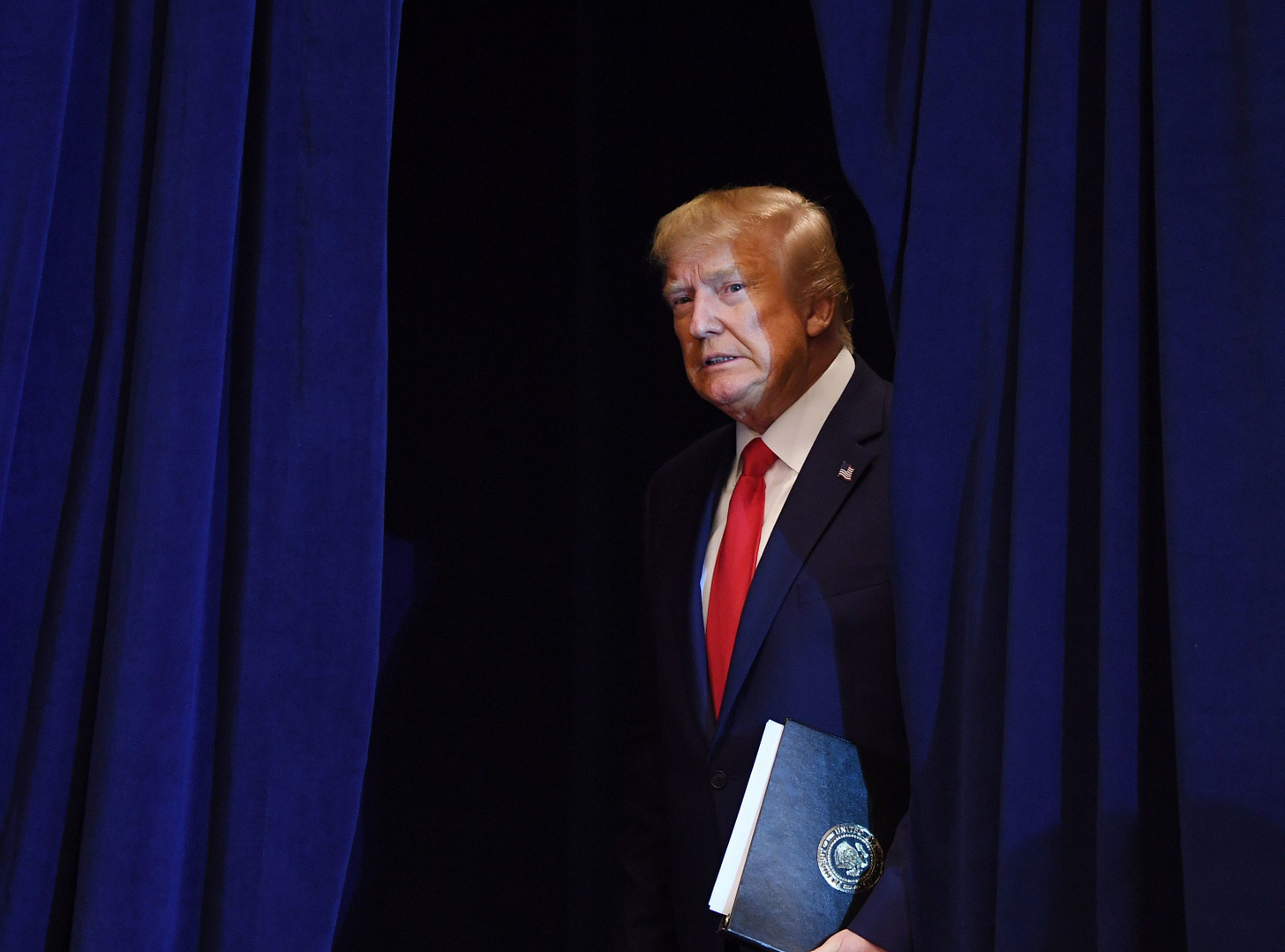

In an October 8 letter to Congress, White House counsel Pat Cipollone made a specious argument that categorically renounced the impeachment inquiry as unconstitutional on the rationale that Donald Trump’s due process rights are being violated.

Not so.

Due process protects regular people from an overbearing, arbitrary hand of government that attempts to deprive individuals of “life, liberty, or property” without notice and an opportunity to be heard first. The Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause (the one that binds the federal government) is not intended to protect officeholders—such as the individual who heads the entire federal criminal and military apparatus—from political investigation or a House impeachment trial. Moreover, while a criminal defendant might be sentenced to a fine or imprisonment, a conviction in the Senate means that the president only loses his job. Even targets of grand jury investigations don’t get the panoply of “rights” that Cipollone wrongly claims the president deserves under the Constitution at the House stage of the impeachment proceedings—namely, the right to call and cross-examine witnesses, to have counsel present during each stage of the process, to have access to the evidence, to get transcripts of the testimony, and “many other basic rights guaranteed to all Americans.”

That said, as Republicans have pointed out, the full House of Representatives held votes formally triggering the impeachment inquiries for presidents Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton. For both Nixon and Clinton, the impeachment process began with resolutions giving the Judiciary Committee the power to conduct an investigation into whether grounds for impeachment existed. Republicans argue that this precedent—although not binding—should be followed here.

In 1868, however, after Andrew Johnson dismissed the Secretary of War in violation of a statute that required Senate approval, the House voted on a “Resolution providing for the impeachment” of the president for “high crimes and misdemeanors in office.” A vote on the actual articles of impeachment came a few days later. For Johnson, then, there was no threshold vote on an impeachment inquiry, so historical precedent isn’t uniform.

That said, there is a legal and strategic rationale for holding a House vote at this juncture. Per Cipollone’s letter, the White House is refusing categorically to respond to congressional subpoenas. For Nixon and Clinton, the subpoenas came through the judicial branch, not Congress. Encouraging Monica Lewinsky to conceal gifts subpoenaed by independent counsel Ken Starr was among the items listed in the articles of impeachment for Clinton. Nixon balked at a subpoena from special prosecutor Leon Jaworski for the White House tapes, losing the challenge in the U.S. Supreme Court.

For congressional subpoenas, the 1961 decision in Wilkinson v. United States is more on point. In that case, a witness refused to answer questions about his Communist party affiliation when subpoenaed to testify before a subcommittee of the House Un-American Activities Committee, which was investigating Communist infiltration in the South. The witness cited First Amendment concerns, claiming that “the Congress cannot investigate into an area where it cannot legislate.” He was convicted of violating a statute making it a misdemeanor for refusing to answer any question pertinent to a congressional inquiry.

The Supreme Court upheld the conviction, reasoning that the investigation was authorized by Congress, that the subcommittee was pursuing a valid legislative purpose, and that the questioning was pertinent to the congressional inquiry. It rejected the First Amendment claim.

Arguably, a House vote to instigate formal impeachment hearings would strengthen Congress’s hand should the stonewalled subpoenas reach the federal courts through the filing of a civil action. (We can expect that, unlike in Wilkinson, the Department of Justice under Attorney General Bill Barr won’t take up a criminal action to enforce Congress’s subpoena prerogative.)

But impeachment is an express power entrusted to the House in Article II of the Constitution. There’s no debate here about squishy constitutional language, originalism, or a “living Constitution.” Nor does this text involve arcane English that people today cannot readily comprehend. The House unequivocally has the power it is currently exercising.

If this issue reaches the Supreme Court on the merits, even conservative-leaning justices will likely agree: Impeachment proceedings are not unconstitutional.