India Has Become More Religious in Recent Years. Here’s Why That Matters.

Pew data paints a mixed picture of religion and tolerance in the world’s biggest democracy.

One hundred years ago, in July 1921, a headline in the Literary Digest declared the United States the “most religious country on earth.” Even today, America is often described as the “most religious country in the developed world”—and it’s true that, while surveys show that religious membership and belief in God have been declining here for many years, the American people remain by many measures much more religious than their counterparts in much of Europe.

But by some measures, one of the most religious countries on earth today is India—a fact with important implications for its democracy, its relations with its neighbors, and its future role in world affairs. Indeed, over the past decade and a half, India was one of the few countries to become more religious. Like the United States, where about 70 percent of the people identify as some kind of Christian, India also has a dominant religious group, Hindus. However, also like the United States, religion in India is fairly diverse—with large numbers of Muslims, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, and Christians. Historically, there has been friction among these groups, and even now religious issues often dominate the headlines in India. But a recent poll from Pew suggests that things may be better than they appear.

About 80 percent of India’s population is Hindu, accounting for about 94 percent of the world’s Hindus (around a billion people). About 14 percent of the country’s population (some 200 million people) is Muslim, constituting about 11 percent of the world’s Muslim population.

More than 95 percent of the Pew poll’s respondents say that religion is important or very important in their lives. Religious identity is also important to people but interestingly, this has led to a syncretic identity of sorts with different religious groups adopting each other’s customs. A fifth of Muslims and 31 percent of Christians celebrate the Hindu festival of Diwali, while 17 percent of Indians celebrate Christmas despite the Christian population only totaling 3 percent.

The syncretism has its limits. Many Indians are not comfortable with the trend toward the miscibility of customs, preferring some level of religious and caste-based separation, and the Pew poll intriguingly explores some of the practical implications of that preference. For example, roughly 80 percent of Indians say they believe it is “important” to stop people from their community from marrying into another religion or another caste. Despite this, 80 percent of Indians said that respecting other religions was a “very important” part of living their own religion, and another 15 percent said it was “somewhat important.”

Just as the United States has major religious differences by region, strong regional variety exists within India, according to the survey. Historically, South India has been a stronghold of the opposition Congress party; even today, most of it is ruled by the Congress and other opposition parties. This differing political identity also has a differing religious identity to match it—Hindus in South India live differently than their northern neighbors. For instance, 18 percent of Hindus say a person can be a Hindu if they eat beef—only 9 percent of Hindus in North India and 8 percent of Hindus in Central India agree with the premise. However, the topic is more controversial in the South—41 percent say yes and 50 percent say no. This difference is also apparent in other religions as well—12 percent of Indian Muslims say a person can be a Muslim if they eat pork and while the numbers are low in North (17 percent) and Central (3 percent) India, they are significantly higher in South India (29 percent).

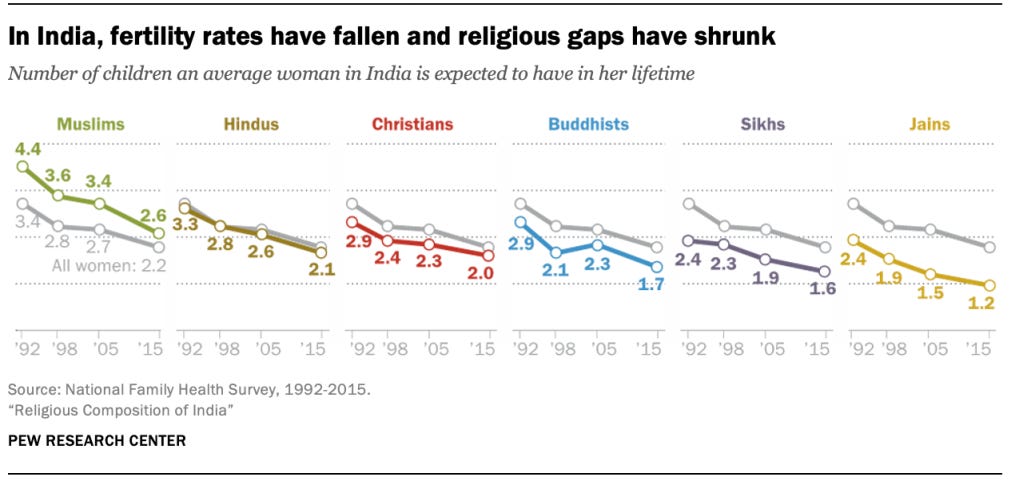

One striking subset of the Pew data involves religion and fertility.

As Robert Zubrin has noted, “Since the time of Malthus, India has always been a prime target in the eyes of would-be population controllers.” A half-century ago, Paul Ehrlich opened his 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb with a disturbingly animalistic description of a “stinking hot night” he spent in Delhi. Ehrlich was convinced that there would be no way to feed the growing numbers of Indians, and that India must, as he put it in a 1967 speech, be allowed to “slip down the drain.”

The Western obsession with India’s growing population led to funding (including considerable U.S. funding) for mass sterilization campaigns in the 1960s,’70s, and ’80s. Millions of Indians were sterilized. The Indian and foreign instigators of these policies failed to understand how innovation—in the form of the Green Revolution—would make it possible to feed the country’s growing population.

They also apparently failed to understand that India’s fertility rate would start to fall. By the end of this decade, India is projected to surpass China as the world’s most populous country. But the Pew data show that in the last three decades, the fertility rate for each of India’s major religions has fallen rapidly. India’s Muslims have a fertility rate above the replacement rate of 2.1, but even they have seen the “most significant decline” in fertility. India’s Hindus and big religious minorities are all at or below replacement:

If these fertility trends continue, and if India’s population doesn’t grow significantly because of immigration, the country’s population growth will inevitably level off, and within decades India’s population will begin to shrink. The higher fertility rate among India’s Muslims suggests that the minority Muslim population will grow as a share of the overall population, unless the Muslims, too, sink below the replacement rate in the years ahead.

Finally, the impact on religious sentiment of the last seven years of political developments—since Narendra Modi became prime minister—is also clear in the Pew poll. Modi’s party, the BJP, had a favorability of +39 in the poll, whereas the Congress party had a favorability of +22. The BJP’s numbers were significantly strengthened by the fact that 62 percent of Hindus viewed them favorably with only 48 percent saying the same about the Congress party.

None of the religious groups polled especially favorably about the Congress party—its best numbers were among Christians but even then, only 58 percent had a favorable impression. This development is reflected across the political landscape—minority religious groups have begun to desert the Congress party and move to outfits made explicitly for them. For instance, Muslims now have Asaduddin Owaisi’s All India Majlis-e-Ittehad-ul-Muslimeen (All India Council for Unity of Muslims) as an option. The party had a presence in elections this year and Owaisi has suggested they plan to compete in elections next year.

That alignment of minority parties and minority religions, when taken in combination with the country’s overall rising religiosity and disturbing rates of religious persecution, and a strong preference among many Indians not to have friends and neighbors of different religions, hint at troubling possibilities for political-religious clashes in the years ahead.