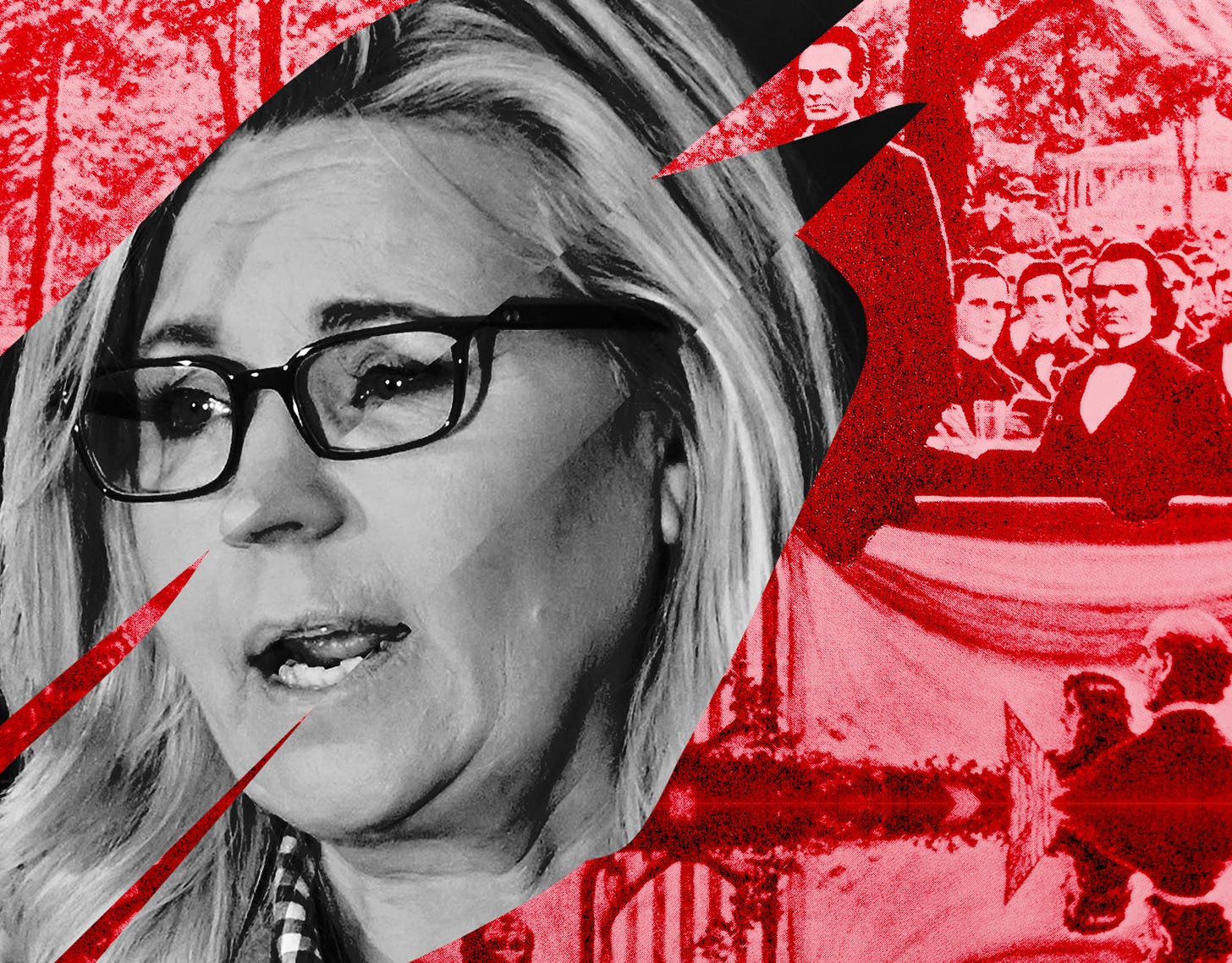

Abraham Lincoln featured prominently—and appropriately—in Liz Cheney’s very fine and not very concessionary concession speech Tuesday night.

Early in her remarks, Cheney noted that “the great and original champion of our party, Abraham Lincoln, was defeated in elections for the Senate and the House before he won the most important election of all.” She reminded us, however, that “Lincoln ultimately prevailed, he saved our union, and he defined our obligation as Americans for all of history.”

Cheney then quoted the final sentences of the Gettysburg Address, and asserted that Lincoln’s words continued to point to “our greatest and most important task.”

And later in her remarks, Cheney invoked the example of Lincoln and Grant, who “pressed on to victory” in the fight to save the Union.

Cheney’s appeals to Lincoln were altogether fitting and proper. Watching the speech, I was moved by them, even inspired by them.

And I agree with them. As Lincoln wrote in a letter on November 19, 1858, shortly after his loss to Stephen Douglas, “The fight must go on. The cause of civil liberty must not be surrendered at the end of one, or even, one hundred defeats.”

So I’m all in on the Lincoln 1858 analogy. His defeat in 1858 laid the groundwork for his 1860 victory. The defeat seemed to be a setback at the time, but it didn’t mark the end of Lincoln’s political career. More broadly, I’d say that Lincoln’s political journey in the 1850s, punctuated by the defeat in 1858, is not just an inspiring story but an educational one. It provides lessons in principled, but effective, political leadership from which there’s much to be learned about politics, and about statesmanship.

So again: I’m on board for the appeal to the Lincoln of 1858.

But I will add this: Looking at the Wyoming election returns in the cold light of the next day’s dawn, and considering them in the context of the Republican party’s trajectory over the past seven years, I couldn’t help but think of another moment in Lincoln’s career: His speech in 1838, given by the 28-year-old little known lawyer to the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois.

That address was delivered just after the conclusion of the presidency of an earlier demagogue, Andrew Jackson; it was delivered as mob violence flared in America with respect to race but also other issues; it was delivered as the prospects for the ultimate peaceful extinction of slavery in the South began to recede.

It's worth quoting the first few paragraphs of the Lyceum Address in full:

As a subject for the remarks of the evening, the perpetuation of our political institutions, is selected.

In the great journal of things happening under the sun, we, the American People, find our account running, under date of the nineteenth century of the Christian era. We find ourselves in the peaceful possession, of the fairest portion of the earth, as regards extent of territory, fertility of soil, and salubrity of climate. We find ourselves under the government of a system of political institutions, conducing more essentially to the ends of civil and religious liberty, than any of which the history of former times tells us. We, when mounting the stage of existence, found ourselves the legal inheritors of these fundamental blessings. We toiled not in the acquirement or establishment of them—they are a legacy bequeathed us, by a once hardy, brave, and patriotic, but now lamented and departed race of ancestors. Theirs was the task (and nobly they performed it) to possess themselves, and through themselves, us, of this goodly land; and to uprear upon its hills and its valleys, a political edifice of liberty and equal rights; ’tis ours only, to transmit these, the former, unprofaned by the foot of an invader; the latter, undecayed by the lapse of time and untorn by usurpation, to the latest generation that fate shall permit the world to know. This task of gratitude to our fathers, justice to ourselves, duty to posterity, and love for our species in general, all imperatively require us faithfully to perform.

How then shall we perform it? At what point shall we expect the approach of danger? By what means shall we fortify against it? Shall we expect some transatlantic military giant, to step the Ocean, and crush us at a blow? Never! All the armies of Europe, Asia, and Africa combined, with all the treasure of the earth (our own excepted) in their military chest; with a Bonaparte for a commander, could not by force, take a drink from the Ohio, or make a track on the Blue Ridge, in a trial of a thousand years.

At what point then is the approach of danger to be expected? I answer, if it ever reach us, it must spring up amongst us. It cannot come from abroad. If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.

I hope I am over wary; but if I am not, there is, even now, something of ill-omen, amongst us. I mean the increasing disregard for law which pervades the country . . . Prophetic in 1838. Timely for us.

I hope I am being “over wary” in letting my thoughts drift from 1858 to 1838.

I hope I am being over wary in worrying that we are only in early days of a period of erosion of civic spirit and civic virtue, of failures of political understanding and political leadership.

I hope I am being over wary in worrying that our current situation could culminate in a ghastly outcome.

I hope we enjoy a reasonably quick reversal of fortunes.

I hope that in just a few years we look back at Liz Cheney’s defeat as an unfortunate aberration, a wake-up call that mobilized a successful effort to halt and reverse the decline.

Reasonable hopes. But it’s also worth realizing that the fight could be longer than we hope. And it’s worth acknowledging that the path to success could be more winding and more challenging than we now suspect it could be.

As Cheney said Tuesday night, “We must be very clear eyed about the threat we face and about what is required to defeat it.”

Historical analogies are highly imperfect and political prophecies totally uncertain. Are we in the equivalent of 1858 or 1838 or something else entirely? We don’t know.

We do know that, as Lincoln said in August 1864, “the struggle should be maintained, that we may not lose our birthright. . . . The nation is worth fighting for, to secure such an inestimable jewel.”

And we do know this: All honor to Liz Cheney, who reminds us of the meaning of political principle and personal courage, and who has demonstrated both in a party that now has neither.