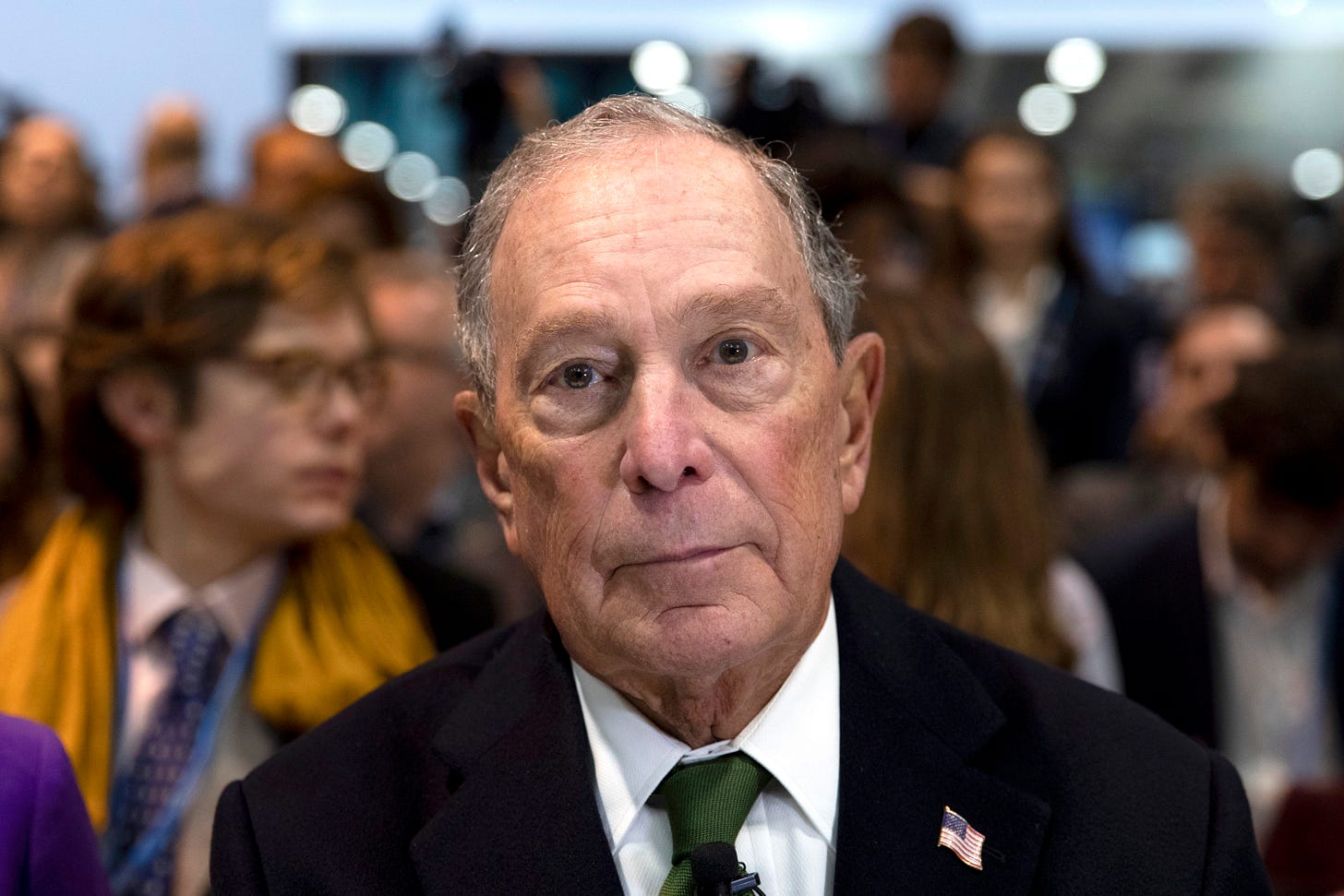

Is Mike Bloomberg Ready For His Close-Up?

The Democratic party is about to take a hard look at Mayor Mike.

Coming out of the New Hampshire primary, it looks like the campaign for the Democratic nomination is headed towards Bernie versus an anti-Bernie. Each candidate will serve as a surrogate for one of the wings of the divided Democratic party. The battle will be between the mostly young, policy-oriented warriors for fundamental economic and cultural change on one side versus the older, more centrist voters whose primary concern isn’t policy, but a return to normalcy, decency, competence, and constitutional order on the other.

Following Elizabeth Warren’s disappointing showings in Iowa and New Hampshire, Bernie Sanders is now the clear frontrunner for the Bernie Lane. With Warren down (but not out), the real action in the near-term will be in seeing how the anti-Bernie lane develops.

It’s for this that Mike Bloomberg has thrown his hat and a few hundred million dollars into the ring on a calculated gamble that, so far, seems to have pieces falling into place.

Joe Biden is one blunder away from becoming the Jeb Bush of 2020. Finishing a distant fourth in the Iowa caucuses was a heavy blow. His single-digit fifth place in New Hampshire may well have been the coup de grace. Biden’s veneer of electability is gone. Like it or not, Trump has succeeded in tying Hunter Biden around his father’s neck like an anvil. Nobody is (or ever was) fanatically enthusiastic about him in the first place. He looks (forgive me) old. Plus, Pete Buttigieg, Amy Klobuchar, and Michael Bloomberg provide moderate Democratic voters other ports in which to ride out the Sanders storm.

Buttigieg and Klobuchar aren’t much better positioned than Biden is: Both look more like placeholders than legitimate contenders. While it remains remotely possible that one of them could pull away from the other, it seems more likely that Klobuchar will regress to her mean and Buttigieg won’t have the juice to consolidate the moderate lane, especially without the support of African-American voters.

Which brings us to Michael Bloomberg.

Bloomberg oozes sobriety and competence, important assets in the fight against Trump. He is superbly well-organized, possessing both the intellect and resources to run an effective, nationwide campaign. He has aired the most effective anti-Trump ads of the political season, all the while avoiding slinging mud at his Democratic rivals. For the most part (more on this later), he was a successful mayor of New York City. He has contributed billions to causes dear to the Democratic electorate, showing a steadfast commitment to gun control, education reform, the environment, the arts, and public health.

He’s also sane—that counts, especially in the age of Trump. And he’s beholden to no one.

But Bloomberg also has serious problems that he will have to overcome, or at least mitigate, in order to capture the anti-Bernie lane for himself.

Four in particular.

First, Bloomberg has a steep climb to earn the necessary support from African-American voters.

In order to earn enough of that support to put him over the top, Bloomberg will have to address at least three issues: (1) His enormous expansion of New York City’s stop-and-frisk program and, perhaps even more disturbing, his too-recent defense of that program in bluntly racial terms; (2) His seeming to blame the financial crisis in part on the discontinuation of red-lining, an unconstitutional and racially-fraught practice by which banks excluded entire minority neighborhoods from obtaining home mortgage loans; and (3) His administration’s steadfast opposition to the civil rights lawsuit filed against New York City by the Central Park 5.

These are real, not made-up, grievances that will at the least lower the ceiling on Bloomberg’s support from the African-American community. He has to deal with them to avoid making the ceiling so low that it crashes into the floor.

His apologies for stop-and-frisk have been accepted by some, but not others. While we can perhaps discount the parsing of his words by the apology police, there is no escaping that these apologies came too late, conveniently corresponding in time to the announcement of his candidacy.

Bloomberg’s red-lining comments are also problematic, but at least somewhat ambiguous. His spin on them—that what he was really saying was that something good (the fight against red-lining) was followed by something bad (the financial crisis)—requires a somewhat tortured reading of his words. But it isn’t entirely implausible, and it is consistent with Bloomberg’s opposition to predatory lending and his other efforts to craft innovative strategies to reduce evictions and help black families buy homes. So he may be able to claim the benefit of the doubt on this one.

His administration’s defense of the lawsuit brought by the Central Park Five is also gaining a measure of public attention.

After the five men had their convictions vacated in 2002, they filed a lawsuit against the city alleging malicious prosecution, racial discrimination, and emotional distress. The Bloomberg administration defended against the suit vigorously, arguing that the authorities at the time had acted in good faith. Bloomberg has since conceded that the evidence against the innocent men didn’t hold up and accepted their exoneration as the final word. It doesn’t appear to be a top-of-mind issue (yet), and standing alone, it probably wouldn’t be a significant factor. But in combination with the stop-and-frisk and redlining issues, it can’t be ignored.

Bloomberg’s second problem is with women. He has a history of crude, sexist remarks, exacerbated by lawsuits that “portrayed the early days of his company as a frat house, with employees bragging about sexual exploits.” Bloomberg’s elevation of women into key roles at City Hall and his donations of tens of millions of dollars to support women’s health are a counterweight that would be more than enough in a campaign against Donald Trump. Whether the same can be said of a Democratic primary campaign remains to be seen.

Bloomberg’s third problem is that he is a billionaire in a party whose primary target (other than Trump) is the “billionaire class.” He’s the guy who parachuted into the race late, ignored the early primaries, and spent hundreds of millions of dollars to buy himself into contention for the nomination of a party that loathes big money in politics.

There’s no way for Bloomberg to escape his “billionaire problem” during the primaries, especially if the race boils down to him against Sanders. But if he inherits the mantle of electability that Biden seems to have lost, and if he directly and honestly addresses his problems with the African-American community, he may be forgiven for his wealth by enough voters to compete effectively against Sanders, who is not without his own baggage.

But Bloomberg’s fourth problem—which I’ll simply call “Bloomberg”—may be the one that costs him the nomination.

He has neither Bernie’s passion, Warren’s retail campaigning skills, Buttigieg’s preternatural self-possession, nor Klobuchar’s warmth. He’s a bit of a stiff who is perceived by many on the left as lacking “empathy, or understanding, for poor people. Or even the average income New Yorkers, and the public amenities that make our city liveable.”

So far, Bloomberg has avoided subjecting himself to a full dose of the media x-ray that ruthlessly exposes the souls of presidential candidates. His rise in the polls has come from saturating the public with the kind of brilliantly-conceived and executed campaign ads that only a billionaire can afford, not personal charisma.

Now it’s his turn in the barrel. In addition to addressing his problems, Bloomberg is going to have to show himself to the voting public. His performance in his first debate, likely as soon as Wednesday night, will be perhaps the most consequential single appearance so far in this campaign season.

Only in a campaign season in which most of the country is desperate to replace the incumbent president could a cranky, short, old, Jewish billionaire with limited retail campaigning skills and serious baggage among African Americans, women and young voters realistically hope to become a competitive candidate for the Democratic nomination.

And yet, here we are.