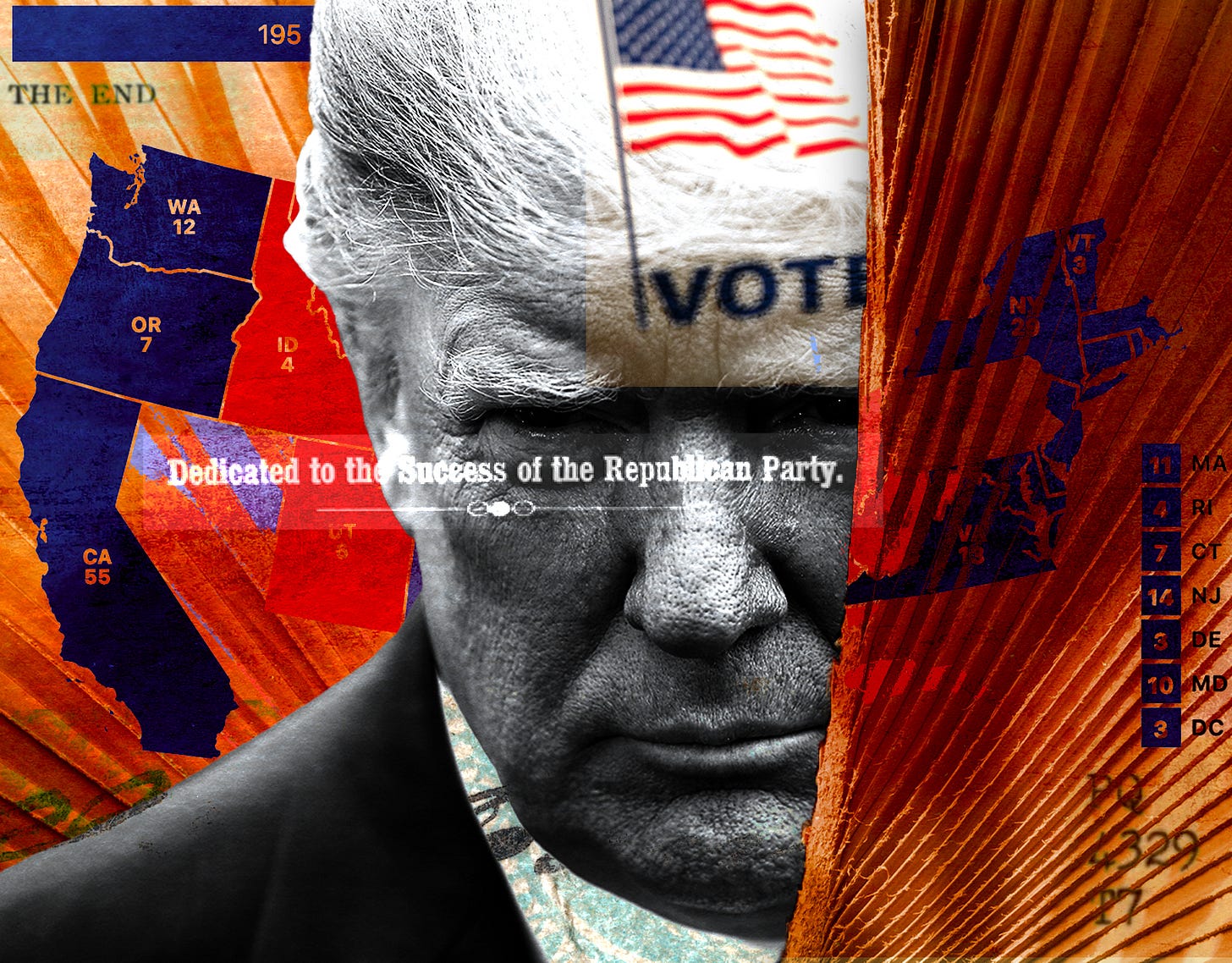

It's Not About This Election, It's About the Next One

The Republican party wasn’t prepared to help Trump steal this election—but they’re being prepared for the next one.

When I first got my hair on fire about Donald Trump's plan to exploit the quirks of mail-in voting to overturn the election results, a good friend of mine gave me a lot of grief for being alarmist. Sure, maybe Trump would try, but there was no evidence that state and local Republican officials would agree to go along with his delusions.

He turned out to be right, for now—but I'm increasingly wondering if it's only for now. Trump's attempt has failed because the ground was not prepared for it.

But the current attempt is preparing the ground, getting the rank and file of Republican to sign on to election conspiracy theories and be ready to demand a different result four years from now.

It's not about this presidential election. It's about the next one.

I became well and truly alarmed before the election after reading a long article describing how Trump was preparing to undermine the vote. I would say this article was prescient, except that Trump had been telegraphing what he wanted to do for months ahead of time—and he has proceeded to attempt all of it.

The basic approach was to take advantage of the "red mirage" produced by the partisan differential between in-person and mail-in voting. Republicans usually do slightly better with in-person voting, while Democrats have an edge in absentee and mail-in voting, but the mail-in vote isn't usually big enough to make much of a difference. During a pandemic year, particularly one in which Trump was downplaying the risks of COVID-19, making his voters less likely to mail in their ballots, that effect was much larger. This produced a window in which Trump could point to an early lead from in-person voting, dismiss mail-in votes as fraudulent—a line of attack he had been preparing all summer—and claim victory on election night, before all the votes were counted.

But this plan required follow-up from state-level officials—either election officials or members of state legislatures—who would be prepared to use this shift as an excuse to throw out the actual vote counts and grant Trump their state's Electoral College votes. Failing that, it required that the Trump campaign try to achieve the same result by filing lawsuits that would end up in the Supreme Court, where Trump believed the majority of justices would back him.

Trump and his people have tried every aspect of this strategy—and failed. Why did it fail? Because not enough people were willing to go along. The first failure was Fox News Channel's decision to call Arizona for Joe Biden relatively early on election night, depriving Trump of the narrative of an election-night victory that would then be "stolen" by late-counted mail-in votes. Then various local officials agreed to certify the final counts that included mail-in ballots and confirmed a lead for Biden in Arizona, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Georgia.

Then Trump's team took his case to court, only to have all but one of his suits tossed out—often contemptuously so—for lack of evidence. (This lone procedural victory was reversed on appeal.) I'm trying to decide whether my favorite is the judge who rejected supposed evidence because it came from an anonymous Internet troll or the judge who took Trump's lawyers to task for making up a quote from a court ruling cited in support of his case.

Trump is now left with a last-ditch attempt to get at least one senator and one House member to object to the tally from the Electoral College, forcing the whole Congress to vote, on the record, on whether or not to accept the results of the election. Even in this scenario, Trump will lose.

But winning this election is not the point any more. The point now is to get a large number of congressional Republicans to officially sign on to Trump’s "rigged election" fantasy.

Many of the crucial decisions that prevented the Trump strategy from working were made by local officials who are Republicans, but who refused to sacrifice the integrity of the system for temporary partisan advantage. Many of the rulings that tossed Trump's spurious claims out of the courts were made by judges appointed by Republican presidents.

These people are Republicans—or were Republicans. Will they remain so? Will they still even be welcome in the party?

I ask because these officials represent the pre-Trump Republican party. The judges were appointed in the two Bush presidencies, and the local election officials rose to their positions within the party either before Trump was in office, or before his influence had extended down to the details of local politics. They did not act like Trump loyalists, because they were selected before loyalty to Trump became the party's central, defining issue.

That increasingly looks like the party's past, not its future.

And that's what the current tussling over the election is really about. It's not about overturning this election. It's about preparing the ground for the next one.

Consider a few scenes from that transformation.

We have Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton filing a suit to invalidate the election results in other states, based on a series of debunked claims. The suit was summarily rejected for consideration by the Supreme Court, but the point is that this is now the sort of thing an ambitious state-level politician does to get himself noticed and boost his standing in the party.

In Wisconsin, Republican lawmakers vowed to hold hearings about voting irregularities at which they would grill the state's election officials. Instead, they have asked not a single official or election expert to testify. Rather, they are calling upon "a conservative radio talk show host, a former state Supreme Court justice, a postal subcontractor who has offered a debunked theory about backdated absentee ballots, and an election observer whom President Donald Trump wants to testify in court in one of his lawsuits over the election."

It's less of a legislative hearing than it is the comments section of a Facebook post.

Thousands of Evangelical Trump supporters marched in Washington, DC, to proclaim Donald Trump's election victory literally as an article of faith, preached to them by such religious luminaries as Alex Jones of the Church of Infowars.

But it's not just the rubes and the fanatics. Former intellectual luminaries of the right have endorsed the fantasy of a "stolen election" and signed petitions calling on state legislators to overturn the results by appointing pro-Trump electors.

Finally, as a threat to back all of this up, there is an alt-right group distributing the names and addresses of local election officials and targeting them for assassination.

These are the forces that are going to be reshaping the party for the next four years. When it next comes time to appoint or elect a state election official, for example, do you think Republicans are going to back the kind of sane technocrat we've seen in this election? Or will the fanatical base view these figures as unacceptable and demand raving true believers?

And then what happens when Donald Trump or some successor to his movement runs again, but with a party that has been thoroughly prepared, propagandized, and purged in order to sustain the narrative of a "rigged election" that needs to be corrected by overturning its results?

Under Donald Trump, the Republican party is resigning itself to the status of a minority party. It is giving up on any kind of "big tent" appeal, doubling and tripling down on pandering to the prejudices of a relatively narrow base. It is as if they have decided they are never going to win an outright national majority again—so they are trying to figure out how to wield power without having to win a majority.

Perhaps I'm being too alarmist. Perhaps with Trump out of office and getting along in years, he will run out of steam, and there will be no successor who can harness quite the same forces. The next election will almost certainly not take place in the pandemic conditions that make the mail-in vote decisive and thus won't present the exact same opportunities for mischief. Perhaps the QAnon people will all go barking off after another target and lose interest.

But after five years of this, of barriers breaking down and guardrails giving out, of previously sober friends and colleagues wandering off in the fever swamps of conspiracy theories, of things that we thought would never happen in a million years happening—I'm more worried about not being alarmist enough.