Jim Jordan’s Bogus Justification for Attacking the Manhattan D.A.

Congress has no constitutional authority over or legitimate investigative interest in the (still only hypothetical) indictment of Donald Trump.

As the country awaits an anticipated criminal indictment of former President Donald Trump, Republican members of Congress have tried to get out ahead of the news by trashing Alvin Bragg, the Manhattan district attorney expected to bring the charges. The rhetoric of Senator Rand Paul (R-Ky.) went the furthest; he said that Bragg, an elected official, should land “in jail” for “a disgusting abuse of power.” Never mind that these GOP critics have been responding to nothing but a hypothetical, because no indictment thus far exists. And grand juries are secret, so unless there’s a public trial, we might never know all of the evidence Bragg’s team has collected.

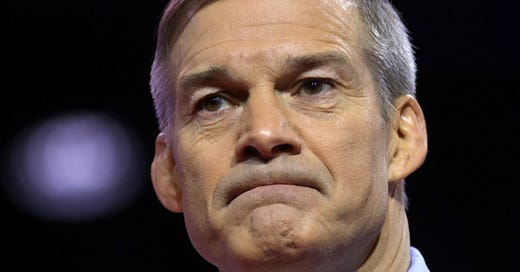

The lack of any authoritative information about an indictment has not deterred three chairmen of House committees from already charging, trying, and convicting Bragg of egregious misconduct. Reps. Jim Jordan (who chairs both the Judiciary Committee and its “weaponization of government” subcommittee), James Comer (who heads the Oversight Committee), and Bryan Steil (chairman of the House Administration Committee) sent Bragg a letter on Monday accusing him of “reportedly” being

about to engage in an unprecedented abuse of prosecutorial authority: the indictment of a former President of the United States and current declared candidate for that office.

They claim that Bragg has “settl[ed] on a novel legal theory untested anywhere in the country and one that federal authorities declined to pursue.” They then take a stab at debunking the hypothetical indictment’s legal theories and the facts that hypothetically might support it—that is, a $130,000 payoff to adult film actress Stormy Daniels by Trump’s former fixer-in-chief, Michael Cohen, to keep silent about her relationship with the presidential contender in the lead-up to the 2016 election, and then Trump’s repaying Cohen in installments falsely recorded as fees for legal services. The trio asserts that Bragg “will erode confidence in the evenhanded application of justice and unalterably interfere in the course of the 2024 presidential election.”

The letter contains some action items, too. It warns Bragg that “we expect that you will testify about what plainly appears to be a politically motivated prosecutorial decision,” then asks him to produce documents stretching back to January 1, 2017, relating to “your office’s investigation of President Donald Trump.” The House members also seek documents involving two former prosecutors—Carey Dunne and Mark Pomerantz—who reportedly quit in protest over Bragg’s hands-off approach to his predecessor’s investigation into Trump’s business practices (an investigation that produced an indictment and conviction of the Trump Organization and a guilty plea by its longtime chief financial officer, Allen Weisselberg, for tax fraud and other crimes).

To be sure, the letter is pure political theater; its aim is to protect Trump, the leading candidate for the GOP presidential nomination in 2024. But as a matter of the U.S. Constitution and principles of federalism—that is, deference to state and local power, which conservative jurists have traditionally revered—the letter is way out of bounds.

The power of Congress to conduct investigations flows from Article I, Section 8, Clause 18 of the Constitution—although that clause actually says nothing about congressional power to investigate, instead stating that Congress “shall have Power . . . To make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution” its other powers. The Supreme Court has long held that the “power of inquiry” is “an essential and appropriate auxiliary to the legislative function.” Congress’s power to conduct investigations is thus implicit in its legislative functions.

This is precisely why, for example, a federal judge rejected the Republican National Committee’s bid to sidestep a subpoena by the House January 6th Committee for internal data about its efforts to fundraise off of false claims that the 2020 election was stolen. (The subpoena was later withdrawn.) Wrote U.S. District Judge Tim Kelly in that case, a court’s “review is ‘deferential’ when assessing whether an investigative act has a valid legislative purpose, bearing in mind that the ‘legitimate legislative purpose bar is a low one’ and that the legitimate ‘purpose need not be clearly articulated.’” After all, the January 6th Committee might have prompted Congress to pass legislation aimed at preventing another insurrection.

To be clear, the GOP-controlled House has not (yet) subpoenaed Alvin Bragg. Nonetheless, it is no coincidence that, for good constitutional measure, the three lawmakers’ letter tosses in a request for documents relating to the D.A.’s “receipt and use of federal funds,” noting that “Congress may consider legislative reforms to the authorities of special counsels and their relationships with other prosecuting entities.” This is their dodgy attempt to find some legitimate cause for federal lawmakers to be sending such a letter to a non-federal prosecutor. The implication is that Jordan and co. need to both hear from Bragg personally and review six years’ worth of documentation collected by his office in order to determine whether federal legislation is warranted around special counsels or other “reforms.”

But this case is different. The prospect of Congress investigating a municipal prosecutor for executing purely local—not federal—law bumps up against another body of constitutional precedent: the power of state and local prosecutors to manage state and local crime.

The Supreme Court has written that “perhaps the clearest example” of the traditional state police power “is the punishment of local criminal activity.” As freshman Rep. Daniel Goldman (D-N.Y.) promptly noted in a tweet, Congress has no legitimate federal interest in how the Manhattan D.A. runs its shop. That’s up to Manhattan voters and the other branches of local government. As put by a federal district court judge in another context, therefore, “this type of insertion into local criminal matters would intrude more deeply into traditional state authority than a mere attempt by Congress to separately criminalize a local crime.” And even for that, Congress would need a reason to believe that activity in a city or state substantially affects interstate commerce under Article I’s Commerce Clause.

This structural separation between the national lawmaking powers that reside in Congress and the powers to delineate and prosecute state and local crimes is a good thing for democracy and individual rights. As the federal Court of Appeals for the First Circuit explained:

By limiting federal jurisdiction over local criminal conduct, and leaving room for state prosecutors to exercise discretion, the Constitution not only protects states’ sovereign policy choices; it safeguards the liberty of the individual from arbitrary power. It gives people within a State the right to be free from federal prosecution for laws enacted in excess of Congress’s delegated governmental powers, powers that are carefully limited within the fifty states.

You would think that members of Congress entrusted with the chairmanship of important committees would care about the constitutional implications of interfering with the delicate balance of power that keeps the federal government out of everyone’s business. But clearly Jim Jordan, James Comer, and Bryan Steil just want to win at all costs.

In his dissenting opinion in Trump v. Vance, which allowed a Manhattan grand jury subpoena for Trump’s financial records to move forward, Justice Clarence Thomas conceded that “under New York law, the decision whether to disclose grand jury evidence is committed to the discretion of the supervising judge under a test that simply balances the need for secrecy against ‘the public interest.’” Only time will tell what New York City voters’ choice for D.A. does with the facts surrounding the Stormy Daniels payoff. If a grand jury of Trump’s peers does choose to indict, then it will be up to a trial jury of his peers to decide his fate. The rest of us—including angry Republican members of Congress—need to wait this one out.