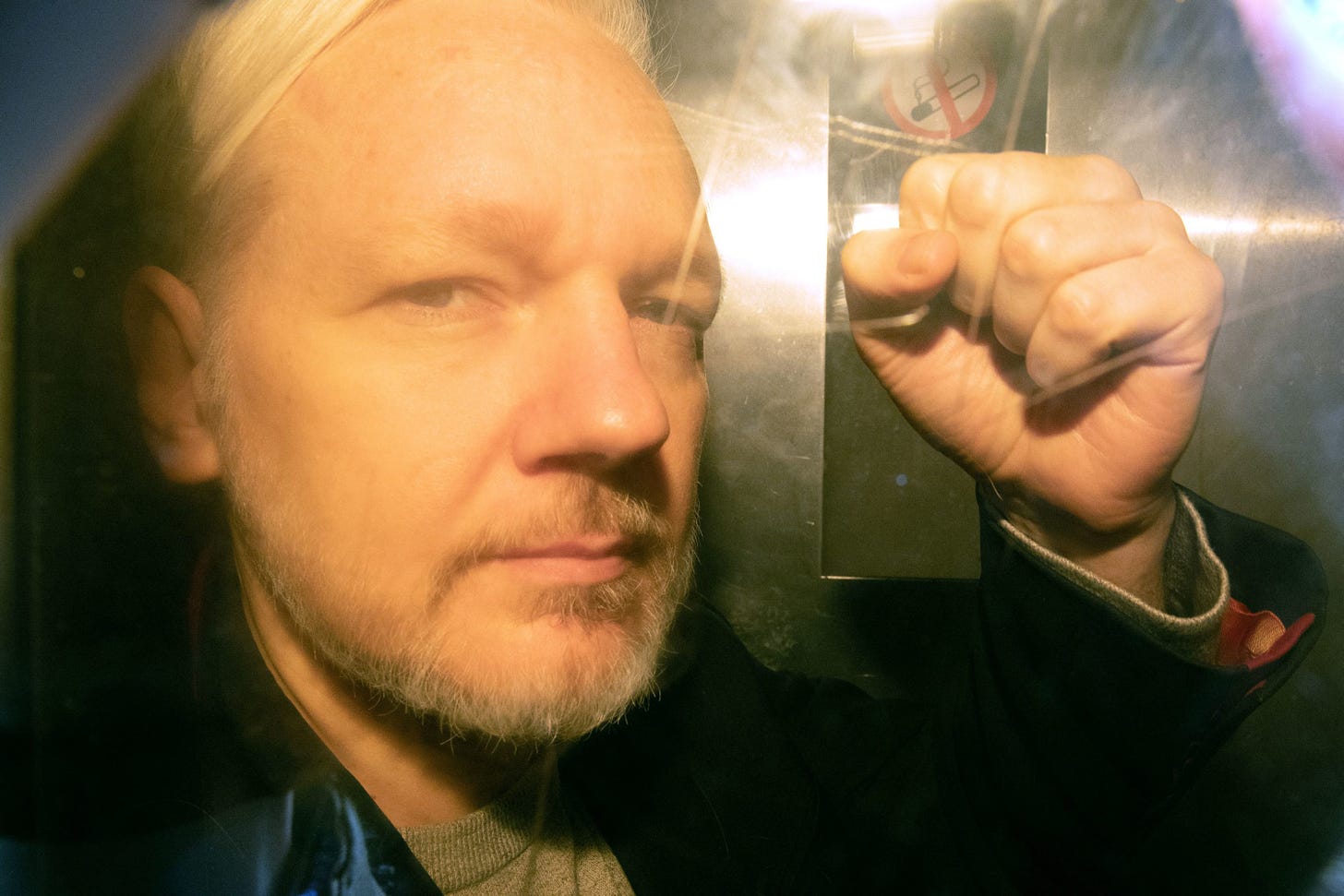

Julian Assange Deserves Justice, Good and Hard

The WikiLeaks founder is no journalist, and treating him like one would endanger both national security and the rule of law.

Following a protracted legal battle, Julian Assange now faces extradition to the United States after a British court ruled in favor of the Biden administration’s request to prosecute the founder of WikiLeaks. Assange has been remanded in the British justice system on the grounds of his faltering mental health, but he may at last be compelled to answer for his role in obtaining and publishing secret U.S. military and diplomatic documents in 2010. He deserves to face justice in the American court system.

According to the indictment a federal grand jury approved against Assange in June 2020,

To obtain information to release on the WikiLeaks website, ASSANGE recruited sources and predicated the success of WikiLeaks in part upon the recruitment of sources to (i) illegally circumvent legal safeguards on information, including classification restrictions and computer and network access restrictions; (ii) provide that illegally obtained information to WikiLeaks for public dissemination; and (iii) continue the pattern of illegally procuring and providing classified and hacked information to WikiLeaks for distribution to the public.

That indictment charged Assange with of conspiracy to obtain and disclose national defense information, obtaining national defense information, disclosing national defense information, and hacking, all related to Assange’s 2010 cooperation with Army private Chelsea Manning to steal and publish classified material. The indictment alleges he offered to help Manning crack a password stored on Defense Department computers connected to a “U.S. government network used for classified documents and communications.” Along with his accomplice, who downloaded four nearly complete U.S. government databases, Assange is charged with involvement in what the Justice Department has called “one of the largest compromises of classified information in the history of the United States.”

Assange’s defenders argue that he’s being persecuted for intrepid journalism. Even some of Assange’s critics have lamented that “For most of these charges, the government does not attempt to differentiate Assange’s behavior from that of a national security reporter.” Of course, there’s no reason why the Justice Department’s prosecution of Assange should be subject to less scrutiny than any other prosecution. But the objection that Assange’s “charges. . . seriously implicate U.S. press freedoms” goes too far.

It’s one thing to note, as Jack Goldsmith has, that legally, the delineation between the New York Times and WikiLeaks—both of which have published classified information—is underdeveloped. It’s another to object to the specific prosecution of Assange as if this case specifically were inappropriate. Amnesty International, for example, has condemned the prosecution as “nothing short of a full-scale assault on the right to freedom of expression,” which is a strange claim to make about a case concerning a single individual.

Assange isn’t being charged with journalistic malpractice. Instead, he stands accused of spying and theft—specifically, breaking into U.S. government computers containing, according to the indictment, “approximately 90,000 Afghanistan war-related significant activity reports, 400,000 Iraq war-related significant activity related reports, 800 Guantanamo Bay detainee assessment briefs, and 250,000 U.S. Department of State cables.”

Assange’s pilfering and dissemination of America’s secrets have done much harm to American interests––and almost certainly endangered valiant Afghans fighting in vain to preserve their own democracy. But Assange’s illicit activities have by no means been limited to challenging America’s “deep state.” Although these actions fall outside the indictment, he also labored to undermine America’s institutions at home. Amid the 2016 presidential campaign, Assange served as an agent of the Russian intelligence services to support Donald Trump and throw the American election into chaos. WikiLeaks published lurid emails hacked from the Democratic National Committee and Clinton campaign chairman John Podesta.

Those who warn darkly of the consequences for press freedom in the Assange case could not be more mistaken. No one has unfettered freedom of action to break the law with accountability to no one but themselves. In all but a narrow legal sense, Assange’s defenders, enthusiastic and otherwise, confuse the exception for the rule: The rule, both in the sense of the statutory law and the pragmatic policy, is that secret government is and ought to be secret, because the publication of classified information can and does imperil he national security of the country, imperiling the foundation of law itself. The exception is that honest, careful, and public-spirited journalists—of which Assange is decidedly not one—are almost always exempted from prosecution of this law because their work is important for the civic health of the country.

Assange has proven that he is not a journalist deserving of deference, but an agent of one (or more) hostile foreign power(s), and he should answer for his crimes to an American court. Far from presenting a test case for journalistic freedom, Assange presents a clear example of why laws against espionage exist in the first place. If he is granted lenience, then the exception will have swallowed the rule, and government secrecy will mean nothing. National security and the rule of law itself will suffer.

In his first State of the Union address, George Washington extolled the spirit of liberty and the virtue of just authority that Assange has so contemptuously transgressed. The “security of a free Constitution,” Washington declared, depends on “teaching the people themselves to know and to value their own rights; to discern and provide against invasions of them; to distinguish between oppression and the necessary exercise of lawful authority; … To discriminate the spirit of liberty from that of licentiousness.”

Those who know and value their own rights should not be tempted to regard Assange as anything but an (alleged) licentious criminal. He ought to be treated accordingly.