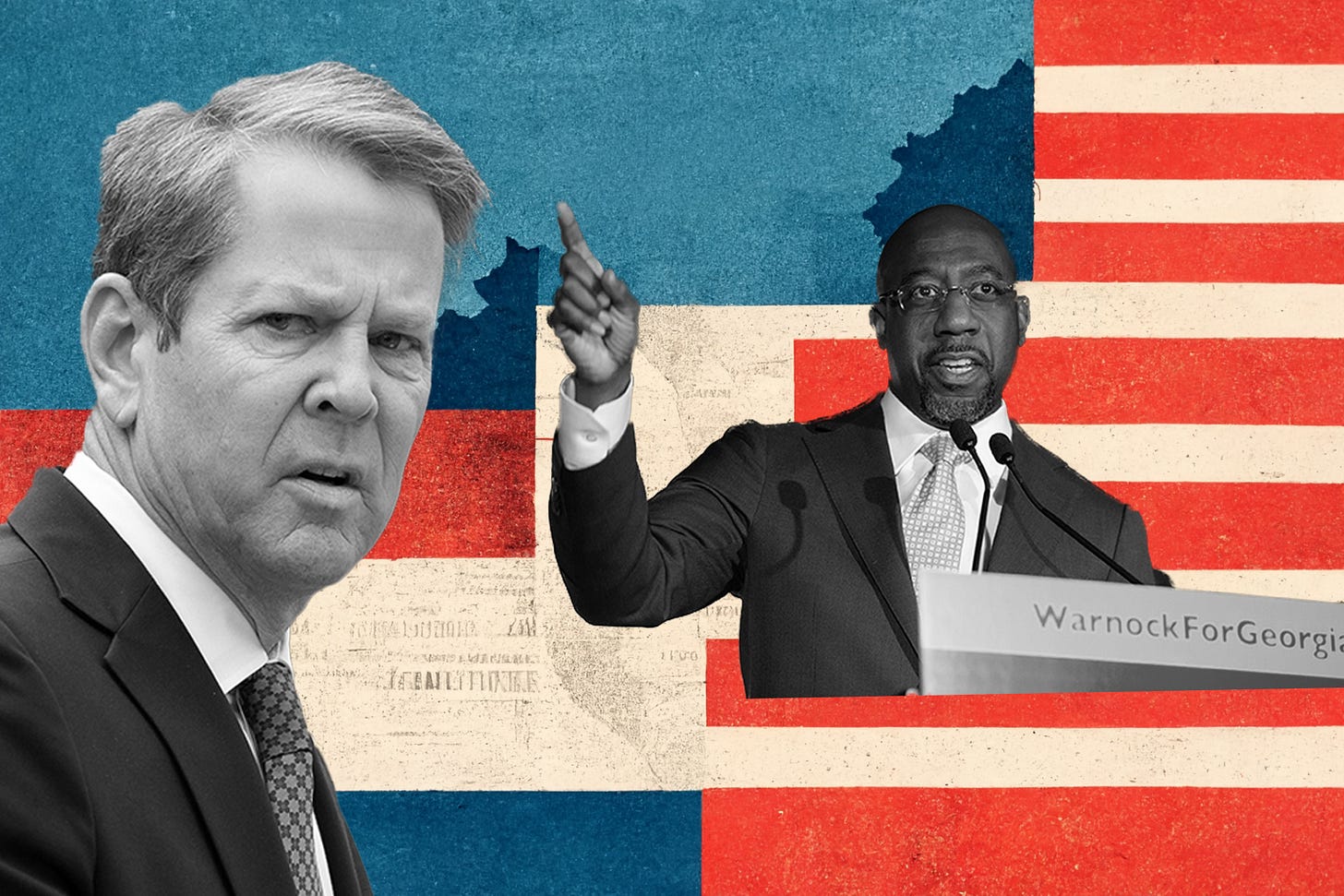

Kemp-Warnock Voters: They’re Real And They’re Spectacular

Voters are splitting tickets in Georgia.

Calhoun, Georgia Last week I went on a pilgrimage to a remote hamlet a few hours inland from the Atlantic seaboard. My aim was to investigate the existence of an endangered species whose possible reemergence could have a dramatic impact on our fragile political ecosystem.

We call this increasingly rare breed: the split-ticket voter.

The split-ticketer’s decline has been thoroughly documented by our foremost political biologists. The number of House districts that have a representative from a different party than their presidential vote has plummeted this decade. Ron Brownstein has written about this phenomenon in both chambers of Congress at length. “In 2016, for the first time ever, every Senate race went the same way as the presidential contest in that same state; in 2020, the same thing happened, except in Maine.” In fact, the current Senate has the fewest split-ticket delegations since the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment gave us the direct election of senators.

So it seems foolish to assume that this century-long trend would be bucked this fall, by two incumbent politicians without particularly heterodox brands, in the exact place where the Senate might hang in the balance for a second straight cycle. Right?

And yet . . .

If there were an ecosystem for the elusive split-ticketer to reemerge, it’s hard to think of a more suitable environment than a place of Wisdom, Justice, and Moderation and the spiritual home of the Red Dog Democrats: Georgia.

The sense that the endangered species of the split-ticketer might recover in Georgia starts with the data. When I landed at Hartsfield-Jackson last Tuesday, the 538 polling average showed the state’s Republican governor Brian Kemp leading Stacey Abrams by 4.5 points (49 percent to 44.5 percent). The same 538 polling average had Democratic Senator Raphael Warnock leading his Republican challenger Herschel “I Hear Dead People” Walker by 2 points (46.5 percent to 44.5 percent).

Some individual polls have shown even more dramatic separation in the races. The latest from Quinnipiac has Warnock leading Walker by 6 and Kemp over Abrams by 2, an 8-point split-ticket spread.

And intuitively, such a gap makes some sense.

After all, Herschel Walker is an unhinged, conspiratorial loon who seems more likely to be a danger to himself and others than the next great American statesman. Whereas Brian Kemp is the incumbent governor of a growing state, a talented retail politician, and ideologically in line with the last few decades of Georgia Republicans. Kemp also managed to step over the ground-level bar of not participating in a coup that would have made a racist game-show host an unelected autocrat.

But relying solely on intuition when it comes to voter behavior isn’t ideal. And as a cloistered coastal elite, my antenna for whom my fellow Americans might find acceptable as a political leader has been off before.

So my search for real-life Kemp/Warnock voters began. And I have to say . . . they were much easier to find than I expected.

Over the course of two days, the Kemp/Warnock voters I found included: a Trump 2020 voter; a past campaign colleague of mine; my college friend’s retired parents; a current UGA student; a suburban Atlanta tax consultant; an exurban Atlanta banker; a couple TDS-addled attendees of my Why We Did It event at Virginia Highland Books; and even the wife of the first man I met at a midday Brian Kemp rally in Calhoun (a small town about halfway between Atlanta and Chattanooga).

Greg Bluestein, the star political reporter for the Atlanta-Journal Constitution, was at that same event and had just finished a story that featured several Kemp/Warnock voters as well. Bluestein’s dispatch included a quote from the head of the DeKalb County Republican Party, Marci McCarthy, acknowledging that she had “several” friends who aren’t voting for her party’s Senate nominee. Which is a rather glaring admission against interest.

Despite the massive spread in these voters' ages and ideological orientations, their explanations for their votes had directionally similar themes. For starters, they thought Brian Kemp is doing a good job and Herschel Walker is a clown. That, I expected. But underneath, a more unexpected trend emerged: For many of the ticket-splitters, it seemed like their perception of Abrams vs. Warnock was as much of a factor as the difference between the Republicans.

My first stop for a sense of all things Georgia is my model red dog, the wife of a high school bestie who went to UGA and is a human encapsulation of the demo that Democrats have gained with the past half-decade. I texted her and asked her to put out an APB for her friends' voting plans.

And the split-ticketers began rolling in immediately.

One, Ansley Thompson, a thirtysomething, stay-at-home mom who had been a straight-ticket Republican voter until 2016, explained her vote this way: She wished Kemp would distance himself further from the election denial/Trump wing, but doesn’t think Abrams has made any “effort to appeal to moderates.” Also, Abrams’s response after losing in 2018 “left a bad taste in my mouth.”

While in Calhoun, I gave Kemp a chance to do as Thompson wished and distance himself from his insurrectionist lieutenant governor nominee. He declined: “I’m going to support the ticket. I’m going to campaign with him.” (Sad!)

As for the Senate race, Thompson summed up her vote this way: “Walker doesn’t have the character or ideology . . . he doesn’t make sense half the time. . . . Sometimes in races like these I’m still tempted to go the write-in or third party route, but I think this race could be close enough that I want to go the pro-democracy, character-matters-most route.”

Admittedly, the Atlanta-area suburban mom is maybe the lowest hanging fruit on the Kemp/Warnock peach tree, but Thompson’s thinking was generally representative.

D.C. Aiken is a colorful former city councilman in Alpharetta, a traditionally Republican city 25 miles north of Atlanta that has moved dramatically towards the Democrats between 2016 and 2020. Aiken wasn’t part of that shift, having voted for Trump in 2016 and 2020, but the post-election insanity that engulfed the state was, for him, the last straw.

He doesn’t like Walker’s connection with Trump and the election fraud conspiracies that are permeating his party. While vamping about the general state of politics, he offered a hilarious aside about how Bridget Thorne, a local candidate in Fulton County, “still thinks Trump is going to win the election.” Here he pauses for the punchline: “The 2020 election.” Aiken told me that while he knows things can get twisted in ads, he thought the attacks being run against Walker are “not disputable,” citing, in particular, the violent threats against an ex-wife.

But what really caught my ear was Aiken’s perception of Warnock as someone who is “more moderate” than his ticket-mate Stacey Abrams. Marci McCarthy,the DeKalb GOP chair, had told Greg Bluestein something similar, saying that what she’s “heard from some conservatives is a sense that Abrams has gone off the deep end, but that Warnock is more acceptable.”

A Republican political strategist in the state—and not one of those Never Trump cucks; an actual Republican strategist—gave equal weight to Warnock’s good campaign and Walker’s crazy:

Herschel Walker is an absolute train wreck and his campaign is one of the more ridiculous I've seen in Georgia politics . . . it’s fundamentally insane. When I’m traveling around or at church or a country club, [people say] “Man, I’m with Kemp, but this Walker clown, I don’t know if I can get excited about him.” . . . [Meanwhile] Warnock has done a good job positioning himself as a safe moderate, despite the fact that his record doesn’t lend [itself] to that. . . . He’s competent, articulate, trustworthy.

Now, I’m not sure there’s actually a whole lot of substance to the perception that there’s some big ideological difference between Stacey Abrams and Raphael Warnock. But in politics, vibes can be reality.

Thus far in the campaign, Warnock has leveraged his background as a pastor who ministers to people of all ideological stripes and an ad campaign that branded him as a suburban dog-loving dad in a half-zip sweater to present as a safe mainstream option for swing voters.

His spokesperson told me this was true to his character, as “long before Reverend Warnock was in the Senate, he was primed to do the work of bringing people together to address challenges based on his time as a pastor.”

In Congress, Warnock has made a concerted effort to burnish a brand as a willing bipartisan dealmaker. He worked as a lead negotiator on the bipartisan semiconductor bill that passed this year, and he authored the bipartisan Invest To Protect Act, which increased funding for smaller law enforcement operations across the country. For this story, his campaign flagged an article showing that he has been the 18th-most bipartisan senator. Which, sure, is kinda like being the 18th-hippest attendee at a Jimmy Buffett concert, but hey, it’s better than being in the bottom 20! And it’s a sign of the Warnock campaign’s approach that they think bipartisanship is a selling point.

Warnock has also avoided stepping on a landmine that has beset Abrams: being seen as the cynosure of The Liberal Elites™. (Google Stacey Abrams Magazine Cover and then Raphael Warnock Magazine Cover if you want a sense for their different approaches in this regard.)

The question is simply whether the combination of Warnock’s mainstream sensibility and Walker’s lunacy will lure enough crossover voters to counter Kemp’s likely margin.

If the strategy works and a black pastor in a Southern state overcomes the historical trends that cut against him—an incumbent president's first midterm and the decline of split-ticket voting—then Warnock’s approach will serve as a model for how someone not named Joe Biden might hold together the Democrats’ unwieldy coalition beyond (or in) 2024.

As for Kemp, I asked the governor’s campaign if they had a specific message for these split-ticket voters. They demurred, saying simply that the “message” is Kemp’s record on COVID and “a host of issues conservatives care about.” That record has been pretty hard-line, frankly. But it has maintained appeal thanks to Kemp’s refusal to go full Trump, despite the fact that the governor bristles at the notion that he should offer even a pinky finger’s worth of difference between himself and the full-throated insurrectionist on his ticket.

I suppose that In These Polarized Times, not actually being the insurrectionist makes Kemp different.

In an alternative universe where the Republican party was looking for a model with an ability to reach crossover voters in 2024, Kemp might be the rare species that offers it. Alas, the GOP doesn’t seem to be sending any explorers to Georgia to survey the fauna. The rest of the party is happy with the snake they know.