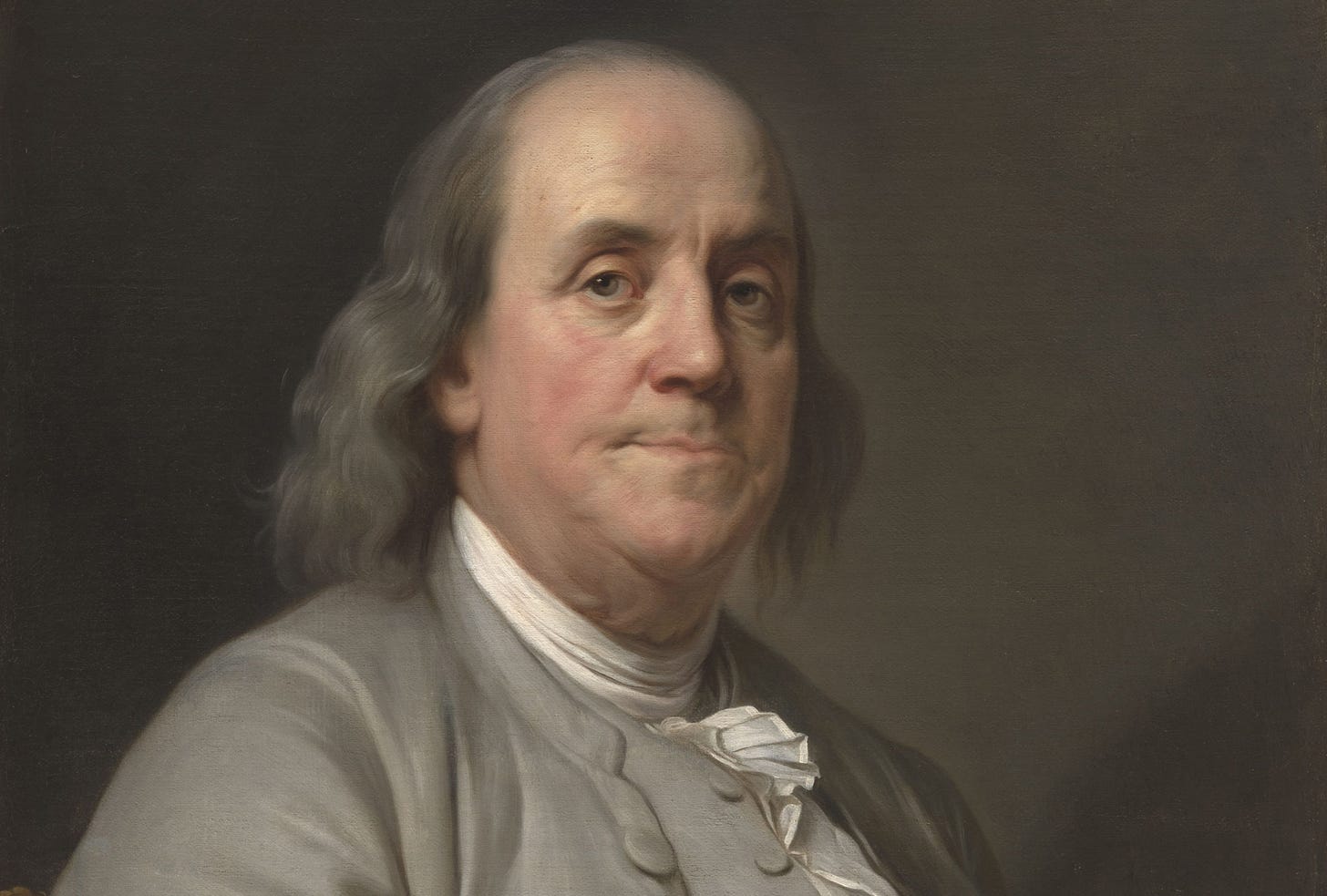

The Worldly Ben Franklin

Ken Burns on the ‘self-made man’ who helped make America.

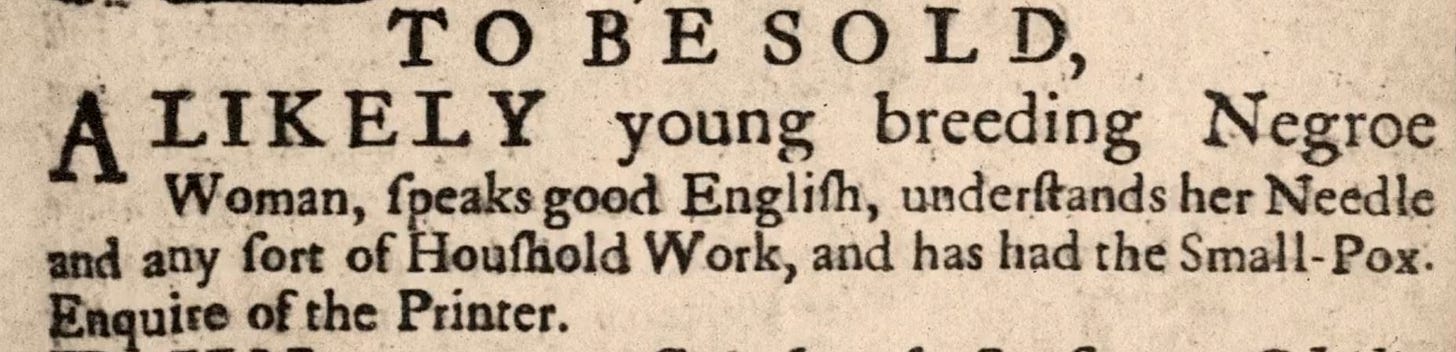

Half an hour into Ken Burns’s new documentary about Benjamin Franklin, we see a page of advertisements that the entrepreneurial polymath ran in his newspaper, the Philadelphia Gazette, in the mid-1730s. Franklin, we are told, ran ads offering rewards for runaway indentured servants, even though he had once been one himself. He also took money for ads offering rewards for runaway slaves, and ran ads offering slaves for sale. It is jarring to see these ads, because Franklin—revered as a Founder, as the “lightning tamer,” as a heroic diplomat during the Revolutionary War, as a leading abolitionist—is not usually remembered as an owner and seller and advertiser of slaves.

Burns’s four-hour, two-part documentary about Franklin is premiering this week on PBS, airing at different times across the country and streaming via PBS.org. The prolific filmmaker is known for his lengthy Civil War and Vietnam War documentaries, and for others he has made on major American innovations (baseball, jazz, national parks) and figures (Mark Twain, Huey Long, Jackie Robinson). Burns strives to portray American history in a way that is accessible to audiences of different backgrounds and ages, and although he is sometimes criticized for being too formulaic—his films do have a recognizable and often-imitated look and feel—and too saccharine, several Burns projects have become cultural touchstones.

With Burns’s customary combination of narration, expert commentators, actors providing voiceovers taken from historical writings, and closeups of archival art and texts, Benjamin Franklin follows its subject’s life chronologically, from his 1706 birth in Boston through his 1790 death as an old man in Philadelphia.

‘Young Franklin at the Press,’ by Enoch Wood Perry, 1876. (Courtesy the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York)

The documentary zips through his early life yet manages to point out most important milestones. Young Ben was indentured to his older brother James, meaning that Ben was contractually bound to work for him, in this case as a printer’s apprentice. Burns shows us some of the sorts of tools Franklin would have used in the print shop. “Printers,” says historian Joyce E. Chaplin, “are setting type upside-down and backward, and you have to be really hyperliterate to understand how language works that way.” Clearly Ben learned an enormous amount in his brother’s shop, but James, nine years his senior, was abusive, sometimes beating him. So Ben broke his indenture and ran off to Philadelphia, where he eventually established himself as a pillar of the community, an inventor, a successful publisher, and a leader in the city’s civic and political life.

Burns and his commentators show us how Franklin became internationally famous for his experiments with electricity and eventually traveled to England to represent Pennsylvania as a colonial agent. He spent most of the years from 1757 to 1774 in England. Toward the end of that period, as tensions grew between England and its North American colonies, Franklin represented three other colonies in England as well—and he found himself hindered in his goal of having Pennsylvania made a royal colony to rid the people of its proprietors, the tax-dodging Penn family. Burns does a good job of showing how Franklin, stuck between wanting to keep the colonies a part of the British Empire and wanting to support them against the growing restrictions placed on them by Parliament, coped with the crisis as it evolved—climaxing in a depiction, at the end of the first episode, of the incident in which Franklin was dressed down by a British official before the Privy Council in the Whitehall Cockpit. Forced to choose, Franklin sided with the Americans.

The Revolutionary War begins early in Burns’s second episode. “It’s hard to understand why [Franklin] even joined the Revolution,” historian Gordon Wood says—after all, Franklin was already successful and an old man: “Many of the 62 other delegates [to the Continental Congress] had not even been born when he first entered political life forty years earlier,” the narrator tells us. It’s not hard, however, to understand why Franklin joined the cause, since his Privy Council humiliation broke his last ties to the Empire. Still, it was not humanly easy: Franklin’s failure to reconcile the familial ties between England and the colonies is mirrored by Franklin’s deteriorating relationship with his son William, the royal governor of New Jersey and a Loyalist. Juxtaposing the political and the paternal in that way is a powerful narrative tool, bringing to life the difficult choices Franklin faced.

In 1776, after Franklin helped edit the Declaration of Independence, he recrossed the Atlantic, heading to France to represent his newly independent country and to secretly seek an alliance. The years in France give Burns plenty of material to work with—more on this in a moment—and make for the most entertaining part of the documentary. Franklin arrived in France the most famous American in the world; by the time he left nearly a decade later, he was the second-most-famous American, having been surpassed by the war hero George Washington.

As Franklin grows into old age—and Mandy Patinkin, the actor who provides Franklin’s voiceovers, lets himself sound gravelly and creaky—we see Franklin continue to shape the country at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 and when he forced his fellow Americans to address the issue of slavery for the first time on the floor of Congress with his Anti-Slavery Petitions in early 1790. The petitions failed, and Franklin passed away a few weeks later, aged 84.

Burns includes in the documentary the voices of experts from various backgrounds, including popular biographers such as Walter Isaacson and academic historians such as the late Bernard Bailyn. The contributions of Erica Armstrong Dunbar, in particular, seem to have significantly shaped the overall narrative of the documentary, based on her on-screen contributions, and her appearance in the credits among the film’s advisers, along with H.W. Brands, Joyce E. Chaplin, Ellen R. Cohn, William Leuchtenburg, Jean M. O’Brien, Page Talbott, and Karin A. Wulf.

While the first episode touched on how Franklin developed affectionate friendships with women, the second episode gets much deeper into the subject, which will come as no surprise to viewers familiar with the popular depiction of Franklin as a party animal and womanizer during his time in France. But they may be surprised by the film’s nuanced discussion regarding Franklin’s time among the French elite, which helps shed light on how friendships between men and women are not the same when crossing cultural boundaries.

Benjamin Franklin surrounded by members of the French court in 1778, during his time as Ambassador. Marie-Antoinette and King Louis XVI are on the right. (Library of Congress)

Unfortunately, even with the inclusion of Stacy Schiff aptly describing Franklin’s time in France, the documentary only scratches the surface of how these intimate friendships helped Franklin succeed diplomatically. Surprisingly, Madame Brillon de Jouy is mentioned only briefly, although she was one of the most valuable connections he made in Paris and contributed to the wedge between Franklin and the prickly John Adams (voiced here by Paul Giamatti, delightfully reprising the role of Adams from HBO’s 2008 miniseries). The few historians who have written on Franklin’s private life and women have either passed away, like Claude-Anne Lopez, or were not featured in the documentary. At least Sheila Skemp’s expertise on Franklin’s wife, Deborah, and son, William, is prominently included. Nonetheless, it’s refreshing to see a depiction of Franklin’s life that is not dominated by the subjects of sex and womanizing.

The way in which the documentary addresses the significance of slavery in Franklin’s daily life exceeds expectations. In the past, biographies of Franklin and relevant histories have tended to not given adequate attention to how Franklin profited from the system of slavery entrenched in all of the original thirteen colonies. Burns showcases how the Quakers, with whom Franklin had long and complicated ties in Philidelphia, viewed the practice of slavery as moral corruption and sin. One of the most powerful moments in the documentary, as noted above, comes when we see the ads for slaves that Franklin printed. “A choice parcel” of “lately Imported” “young Men and Girls, bred to Plantation Business,” says one ad. Another offers up “a likely young breeding” enslaved girl, with the words “Enquire of the Printer” front and center, illustrating that Franklin not only profited from printing the ads but had a more active involvement:

Yet even as Franklin participated in the system of slavery, he ran anti-slavery articles alongside the ads he printed, and supported the education of enslaved black children in Pennsylvania.

This aspect of Burns’s documentary will help viewers have a deeper and more balanced appreciation for how, in an era dominated by human bondage, Franklin went from slaveholder to abolitionist. The documentary doesn’t fail to teach viewers about Franklin’s monumental contributions to science and technology, politics and countless civic projects—but in reminding us that Franklin is a man of flaws, in humanizing him, Burns helps us to better understand why Franklin’s messy, brilliant, ambitious life and example remain relevant today.