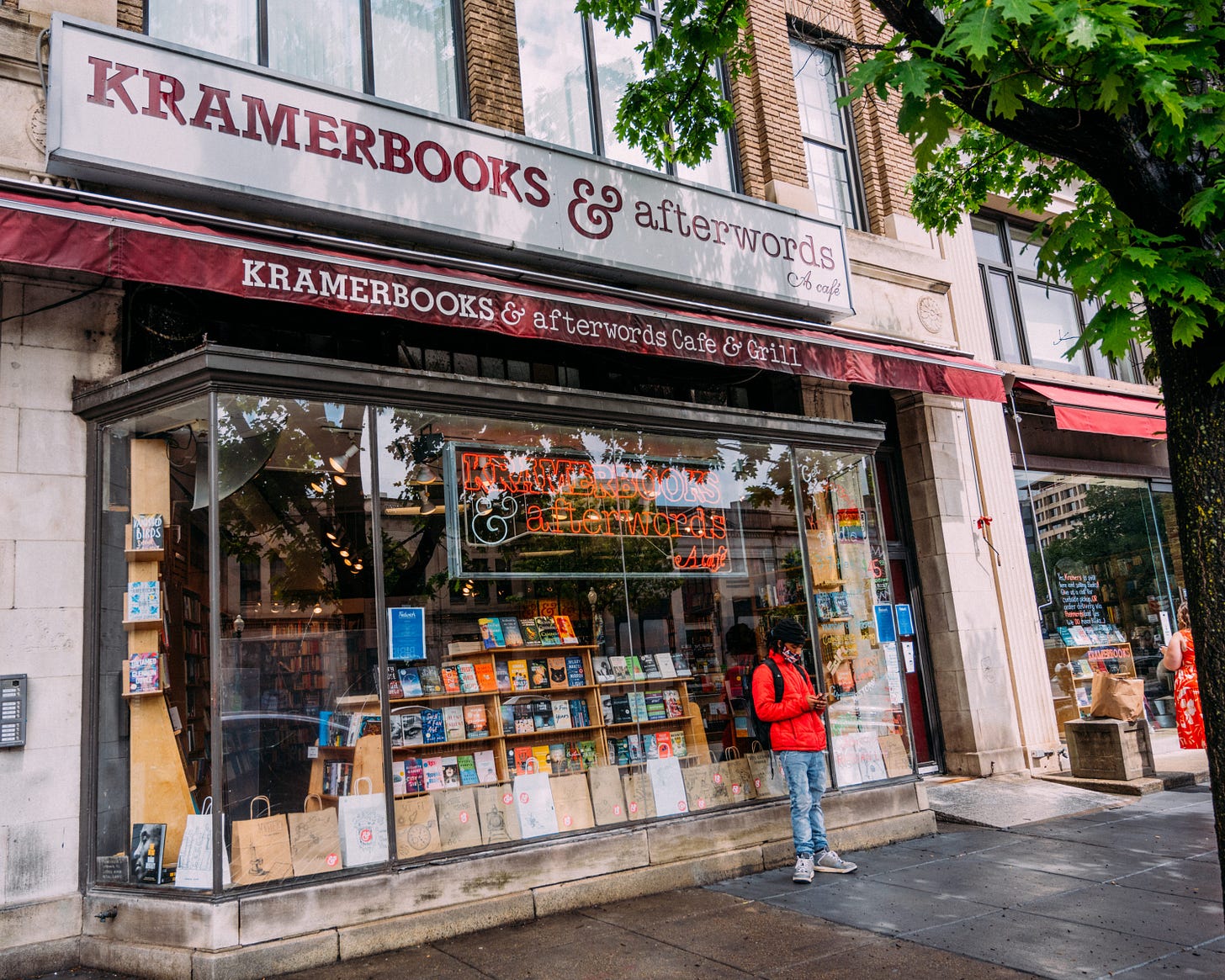

Kramerbooks, Sentimentality, and Me

Dealing with the emotional response to the prospect of losing a Washington D.C. cultural institution.

“I have heard that this pain can be converted, as it were, by accepting ‘the fundamental impermanence of all things.’ This acceptance bewilders me: sometimes it seems an act of will; at others, of surrender.”

― Maggie Nelson, Bluets

As the coronavirus reorganizes cities, the Washington Business Journal reports Steve Salis, the owner of Kramerbooks, is considering moving the bookstore from its Dupont Circle location in Washington, DC. For many this news is disappointing. There is a chorus of lamentations on Twitter. The emotional undercurrent on which many of the protestations ride is one of nostalgia and sentimentality. In De Profundis, Oscar Wilde described sentimentality as wanting “to have the luxury of an emotion without paying for it. We think we can have our emotions for nothing. We cannot.” The Washington Post has published a brief missive from Daniel Drezner expressing sorrow for the store’s potential departure. He writes that nostalgia has gotten a bad rap. The piece is a defense of the overwhelming sentimentality towards the bookstore. “Regardless of the immediate object of our sentimental gaze, the self is also sentimentalized,” wrote Joseph Kupfer in his 1995 essay The Sentimental Self, “Sentimentality is a powerful vice because it is perspectival. It shapes, colors, and conditions what we see and how we see it.” Drezner recognizes the danger of letting nostalgia distort perspective. However, he argues that those who ignore emotional responses and reactions do so in peril. He makes a fair point, but there is a difference between ignoring emotion and indulging overly-rosy sentiment. The specific nostalgia Kramerbooks inspires is dependent on its relationship to the city and the unusual transience of Washington D.C.’s middle class. New York is better acquainted with restaurants disappearing and the turnover of various storefronts. By contrast, the change in Washington is driven by the replacement of people. Washington is a company town and the company is Politics. This means politicians come and go and as they transit, so do a constant stream of schedulers and interns and policy wonks. Not to mention the tourists.

The thing about company towns is the people who work for the company often can’t see the world that exists outside the company. The class of temporary residents and tourists who have a finite period of contact with the city fix it in their minds as a place that once belonged to them. While the people who actually live in the District separate from the world of Capitol Hill and the Cherry Blossoms are ignored. “I only lived in Washington for a brief spell,” Drezner admits in his remembrance of Kramerbooks for the Post, “but in the decades since Kramerbooks was always my focal point for meeting friends and colleagues.” The past is a foreign country, even when you remember it as an idyll.

A message written on the storefront window, May 22, 2020. In an Instagram post the bookstore responded to concerns about the move saying: "DON’T WORRY, WE ARE NOT CLOSING. We are considering a move. We are more committed now than ever to preserve & protect Kramers for another 50 years. Unfortunately, our landlord will not allow us to do so in Dupont Circle. We hope that the situation changes. We will continue to serve the community and keep you well read & well fed, no matter what changes come our way". Photo by Carl Maynard @carlnard for The Bulwark One of the reasons people have been so distraught by the possible move of Kramers is because for decades, the book store stood apart from the carousel of turnover in the city. Its 44 year tenure might not seem as impressive compared to the Strand’s 92 years of prominence, but by Washington standards, it has been around long enough to be considered an epoch. For a sense of the bookstore’s youth, Ben’s Chili Bowl—a family-run restaurant, and probably the most iconic private business in Washington—has been around for 62 years and survived the race riots in the late ’60's that took place almost a decade before Kramers was founded. Washington has so few independent establishments that contribute to the city’s cultural identity apart from the monuments and museums that the potential loss of any seems like a tragedy. Kramerbooks isn’t just another storefront—it is integral to an idea of what the city looks like. It gives a sense of permanence to a place in constant political flux.

An employee hands off an order for delivery. The store also now ships orders through Bookshop.org. Photo by Carl Maynard @carlnard for The Bulwark Like so many, I have my own history with Kramerbooks. I grew up in northern Virginia and I lived in the Southeast quadrant of the District after college. I understand the outpouring of feeling and support for the store. But not the histrionic sentimentalism. This is not an effort at “hip cynical transcendence of sentiment” as David Foster Wallace put it, but a reckoning with my own habits of consumption and behavior. “Sentimentality surreptitiously shrinks our world and concerns to the circumference of ourselves.” Kupfer concluded in his essay, “The self-absorption which feeds off our direct emotional focus makes sentimentality a deceptive, dangerous vice, not something to be brushed off as little more than a genteel foible.” Still, I understand the vice. It’s hard to avoid a glut of emotion when you’re thinking about a place of personal significance. By nature, I am not a sentimental person. But I was sentimentally attached to Kramers for a very long time. Sentimentality is simple and self-reflexive. Actual mourning is complicated. For me, Kramers was a site of quiet, private humiliations. It was also a site of refuge. And disappointment. As a place, Kramers has the same emotional weight in my life as a high school bathroom where I would go to hide rather than socialize in the cafeteria. The most fitting example of Kramers's definitional role in my life is the night of the White House Correspondents’ Dinner in 2017. I was in my early 20s and getting started in journalism after a year of freelance meandering and humanitarian travel. I had a job at a doomed weekly magazine and I had just gotten out of a toxic relationship (a perennial hobby of mine). On that night a friend asked me to meet at one of the rooftop afterparties for Washington’s one night of rented glamour, “Nerd Prom.” But, I was unable to get into the party early in the evening—my friend was held up at the dinner. Growing more and more anxious waiting and feeling ridiculous with my misplaced expectations, in an evening dress and heels, I walked a mile and a half to Kramerbooks. Blistered and bleeding through my shoes when I arrived at the bookstore, I crouched down against the poetry shelf in a puddle of the dress’s sparkling translucent black fabric. I picked up Maggie Nelson’s Bluets and read and read until at last my friend texted to tell me to come back and rejoin the world. I picked up several other books and checked out. I then carried that bag of books around the party like a weighted blanket against my nearly insurmountable anxiety. Jostling through a crowd of new friends and old enemies I wondered what exactly I was hoping to gain from the experience. Why hadn’t I just stayed at the bookstore? In the catalog of liminal public spaces—gas stations and parking lots, libraries and parks, graveyards and churches, stadiums and movie theaters—restaurants and bookstores stand apart and inspire a unique emotional valence for every independent visitor. As the years passed, this is what Kramerbooks became to me: Neutral ground on the threshold of social participation. Whether it was an event or a relationship, I was convinced Kramers was the best place to begin. The best place to linger and kill time, to find and be found. For every occasion seeped in the pain and anticipation of waiting for a party—waiting to be granted admission to the world—I could give you an equal story of feeling at peace among the stacks, or thrilled by discovery. The single best memory I have of Kramers was the 50th anniversary of AWP, the Association of Writers & Writing Programs conference, when Graywolf Press, a non-profit publisher, hosted a party in the bookstore. Which, for me, represented an unsettling reversal of social kismet. Sure the store had an events space and hosted plenty of intimate gatherings and kitschy activities like paint and sip nights, but nothing on this scale, nothing with so many people I held in such high esteem. I wandered through, enthralled by seeing my literary heroes laugh and toast cheers. The store was packed and you could barely move. I was beside myself with joy, briefly happy just to be there in the midst of giants. This is the one memory that ties a knot of nostalgia in my throat, making it hard to swallow the loss of the store as I remember it then in those moments: full of writers, rapturous. https://twitter.com/kramerbooks/status/811367090775085060?s=20 There were other random encounters. I once was lost in concentration looking for something obscure when I realized I was surrounded by plainclothes bodyguards. Grasping for situational awareness I turned around to see Sasha Obama. She was taller than I’d expected, glowing with youth and happiness as she went through the shelves with a friend in cut off summer jean shorts. I remember her smiling. On another occasion I met a young member of the Explorers Club by the fountain in the circle as I was walking towards the bookstore where I had planned to meet a friend for dinner. At the light, he declared this was love at first sight, how surely I was his future wife. He was among friends as well and laughing we all made our way to the cafe where, as a group, we had drinks and told each other stories. He and I walked around the city after, but I lost my nerve and got weird—paranoid for some indiscernible reason beyond the obvious fears of being with a stranger in the night, I was very young, very naive. We parted ways, never to meet again. Then, as the memoirs and hot dish expositions of palace intrigue and the inner workings of Trump’s White House began to trickle out, for work and, sometimes play, I attended almost all of the midnight releases Kramerbooks hosted. Perhaps it was these events that began to turn away my tenderness for the establishment, the true start of a slow souring. It was disheartening, pressing against the machinations of the publishing industry—contributing to the frenzied media attention dealt to books that amounted to no more than flotsam cast off by the administration. They were marketing devices—the lowest tier of literary efforts, the most hollow and empty—yet we were helping them make the most noise. https://twitter.com/weeklystandard/status/949146471902793734?s=20 But despite creeping trepidation, I kept going back. Countless nondescript errand trips for this or that new release. Picking up the required reading with my sister for her high school English class. Shooting headshots for friends in the front window light, the shelves falling out of focus behind them. The Banned Books Week scavenger hunt hosted by the DC Public Library. Buying Christmas presents and notebooks. I even own stemless wine glasses with the Kramerbooks logo on them. And the books. How many books have I purchased from Kramers, hoping against hope they would fill me? Cookbooks, novels, biographies, art and poetry, endless non-fiction. I have collected a full rainbow of their colored card-stock bookmarks, including one of glittering gold.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Kramerbooks & Afterwords Cafe (@kramerbooks) on Jan 29, 2020 at 10:18am PST

The store’s Afterwords Cafe was the site of unsuccessful dates, secrets, and passing flirtations. Too many went poorly, amassing into a prickly backdrop of emotional defeat. The problem with vulnerability and sharing your favorite place with others is you run the risk of them ruining it. Responding to Kupfer, Deborah Knight writes: “[T]he sentimental individual takes pleasure in repeating her experiences of excessive, maudlin emotion.” My attitude towards Kramers has for the majority of my life been defined by sentimental expectation. My dependence on the store as a locus more or less proves her point. So many brushes against the possible. So many close encounters with happiness. There seems to be a rim of light around these memories, but the light never fully enters the picture. Kramers is one of the last places I visited before the lockdown. It is hard to convey how much I enmeshed my life to this place—a true third place—not by design, but by the frequency of habit, compulsion, hope. But instead of retreating to sentiment, it’s better to mourn the loss while looking to the future. For me, it’s an opportunity to look at my cyclical returning and repeated patterns of fear and avoidance. For the community, it’s an opportunity to look at the ways we ask sites to be more than they are to meet cultural needs they have no way of totally fulfilling. Change for the sake of growth can be liberating.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Kramerbooks & Afterwords Cafe (@kramerbooks) on Mar 23, 2019 at 7:57am PDT

“The bookstore is an empire of the spirit that has expanded laterally” Paris bookshop Shakespeare & Company's proprietor George Whitman, once said. Bookstores are mythologized. It is by no fault of Kramers that the store is a place I associate with longing, loneliness, and disillusionment. Taking the good and bad in equal measure there is a certain sense that rejecting the nostalgia others are so acutely experiencing is akin to apostasy. But a bookstore is not a chapel, holy or sacred. Bookstores and books are not substitute for contact, for the real thing.