Le Pen Could’ve Won Here

France provides an example of how American electoral institutions distort voter representation.

It could be said that French President Emmanuel Macron won re-election because he was a moderate candidate with broad popular appeal. That statement may come off as obvious, given that he finished first in the country’s initial round of voting and ultimately defeated his far-right challenger Marine Le Pen by a margin of roughly 17 percentage points in the runoff election on Sunday. But not every country has electoral institutions that produce winners with Macron’s particular traits. In fact, if France used the electoral institutions and processes in place in the United States, the overwhelmingly moderate French electorate would have been stuck with a democratic socialist and a far-right extremist as its final two choices. And the best evidence suggests that Le Pen would have won handily.

As a political scientist, I study how different electoral institutions can produce different political and governing outcomes. In this spirit, I ask you to join me in a thought experiment about the high-stakes French election. France uses a variation of the “top-two” electoral system that has been gaining popularity in the United States: Louisiana, Nebraska, Washington, and California each use a form of top-two. In France, if the leading candidate does not win an outright majority, the candidates with the first- and second-most votes compete in a runoff. Here’s how that transpired this time around. On the first ballot, back on April 10, Macron, Le Pen, and the left-wing Jean-Luc Mélenchon were each favored by roughly a quarter of French voters. Le Pen eked out second place over Mélenchon, sending her to the one-on-one runoff on April 24 against the top finisher Macron. What seemed to bode well for the incumbent were the preferences of voters who selected one of the other nine candidates in the race. According to polls, this group strongly preferred Macron as their second choice to Le Pen or Mélenchon—thus why Macron was favored on the second ballot and ultimately won comfortably. In short: Macron was the most broadly representative candidate of the whole French electorate. But what if we re-ran this election with American rules and systems? For many elections, including presidential elections, the United States uses single-ballot, plurality-rule—meaning whoever wins on the first pass is the victor, even if the top vote-getter receives less than 50 percent. By virtue of what political scientists call “Duverger’s law,” this has produced two major political parties: a party of the left (the Democrats) and a party of the right (the Republicans). Although state election laws vary and the parties set their own rules for nominating presidential candidates, single-ballot, plurality-rule voting is the norm in primary contests, too. If France did politics this way, it’s likely that a little more than a quarter of the French electorate would identify with each of the two major parties, and most voters (say, 40 percent) would affiliate with neither of them. Despite comprising a plurality of voters, this latter group would have little influence on which two candidates would compete in the general election, since the primary process generally shuts out independents. Imagine on top that of the 60 percent of French voters who would identify with one of the two parties, less than half of them—which is to say, less than 30 percent of the full electorate—would even show up for the primary election to determine the nominees. That’s the voter part—what about the candidate part? Instead of a first-round election, in which 12 candidates from 12 different parties compete against each other directly, the French presidential candidates would be forced to self-sort into two major parties to have a chance. Let’s assume that all candidates to the left of center are in the “left party” and all candidates to the right of center are in the “right party.” Macron, who is squarely situated at the ideological center of French politics, could potentially fit into either party—which would make him viable in neither. He would be unlikely to win this particular first-round vote—a party primary—since he does not represent the base of progressive primary voters in the left party or of conservative voters in the right party. Instead, the progressive voters in the left party would likely nominate Mélenchon and the right party would likely nominate Le Pen. And the candidate who enjoys the most widespread support among French voters would be shut out of a general election.

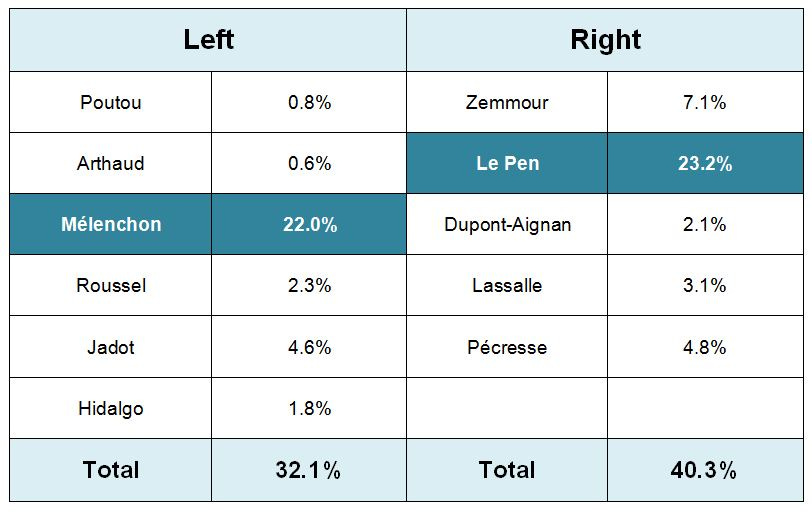

So, who would have won a head-to-head matchup between Mélenchon and Le Pen? I could not find any prominent pollsters who asked respondents for their preference between the two. However, several reliable polls asked respondents whom they would vote for if their top choice were not an option in the runoff. We can use these results to infer how Mélenchon would have fared in a race against Le Pen. First, let’s allocate to Le Pen and Mélenchon the vote share they each received in the real first-round election: rounding to the nearest percentage point, 23 percent and 22 percent, respectively. Second, let’s allocate to Le Pen the vote share of all candidates to the right of Macron, and to Mélenchon the vote share of all candidates to Macron’s left. Altogether, about 40 percent of French voters cast first-round votes for a candidate who was ideologically closer to Le Pen, and only 32 percent cast votes for candidates ideologically closer to Mélenchon. Table 1: Round 1 Actual Vote Share of Candidates

[Source: Wikipedia.]

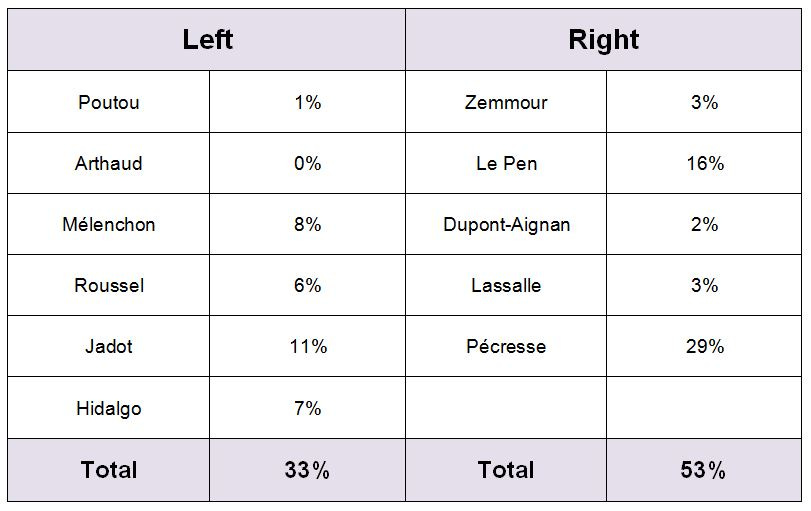

This leaves the 28 percent of French voters for whom Macron was their preferred choice. If Macron’s supporters would have broken for Mélenchon overwhelmingly, then his head-to-head matchup with Le Pen probably would have been competitive. However, an Ipsos poll conducted days before the first-round election found that Macron supporters preferred Le Pen over Mélenchon by a two-to-one margin. More generally, out of respondents for whom Macron was their first choice, 53 percent said that a more conservative candidate was their second choice, whereas only 33 percent preferred a candidate who was more progressive than Macron. These results were not an anomaly; another survey conducted in March found similar trends. Table 2: Second Choice of Respondents Whose First Choice was Macron

[Source: Ipsos poll conducted April 8, 2022.]

This analysis relies on a number of assumptions. This approach doesn’t allow us to make precise predictions about what a runoff between Mélenchon and Le Pen might have looked like—only best guesses based on our counterfactual premise. However, we can confidently say that nothing from the actual round-one results or polling data suggests that Mélenchon would have defeated Le Pen straight-up. The beauty of the French electoral system is that the general electorate could express its dissatisfaction with the political left in the first round, by rallying around a centrist candidate with broad support. This candidate has now twice prevented the election of a right-wing radical whose views are fundamentally at odds with a large majority of French voters. But if France used American electoral institutions that all but guarantee two-party rule, as well as partisan primaries to determine its head-to-head second-round elections, Le Pen would likely be the French president-elect, and the West would have just lost a crucial ally in the global battle against Putin and authoritarianism. Given our own recent experience with an illiberal right-wing president, the United States needs to continue exploring more representative electoral institutions, including the top-two system used in France, which we would generally call a “nonpartisan primary” here. Elections that reflect the will of all voters are not just fair—they safeguard the democratic experiment.