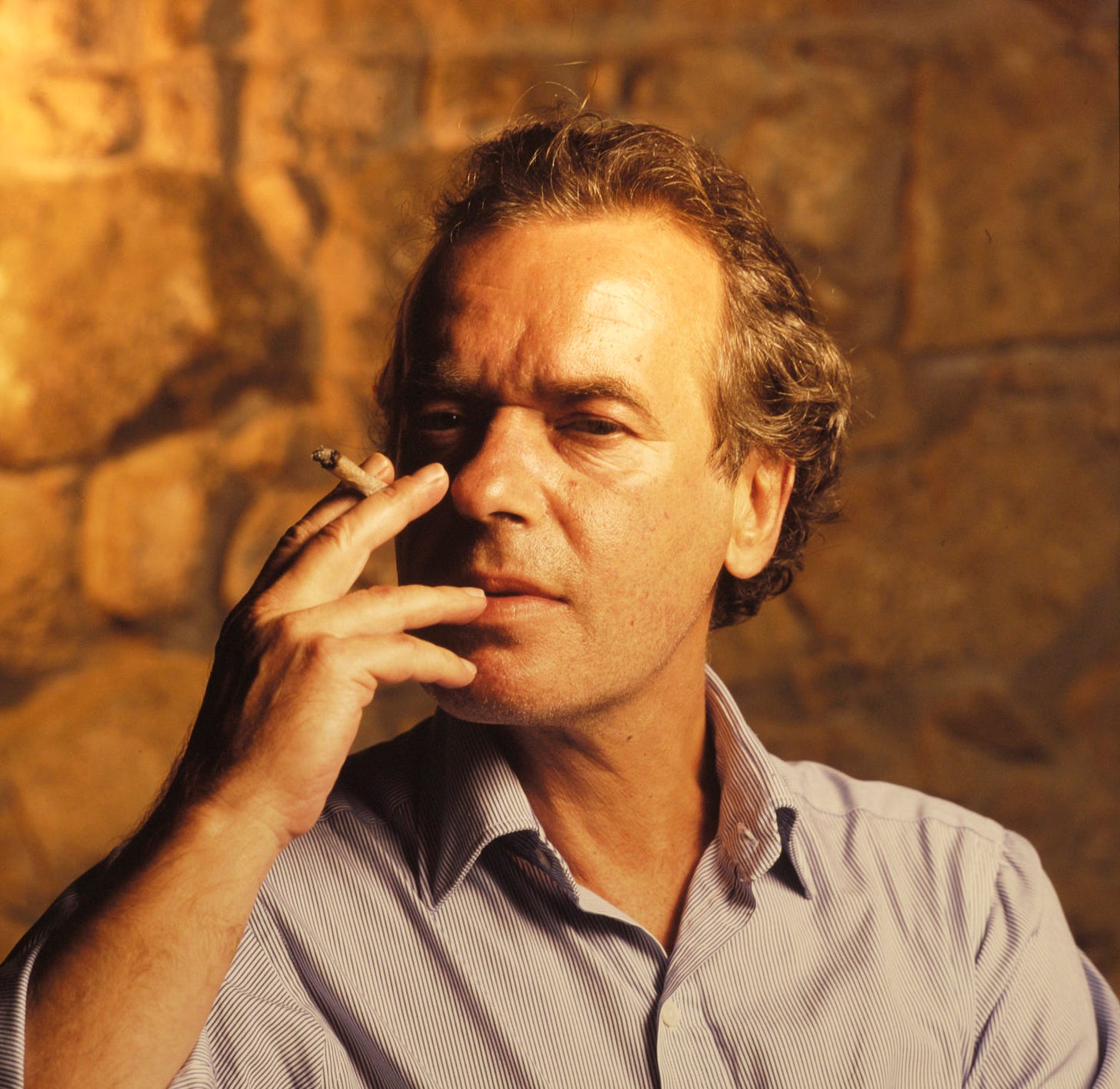

Martin Amis, 1949–2023

A craftsman whose abhorrence of cliché helped create greatness.

Martin Amis, the great British writer who died on May 19 at his home in Florida, once wrote a novel called Time’s Arrow, the premise of which is that time is moving backwards, at least for our protagonist Tod T. Friendly. Over the course of the short novel, the reader learns that Friendly was a Nazi doctor during the Holocaust, except of course in this reverse timeline, the Jews in Auschwitz begin as smoke and ash, travel down through the air into the gas-chamber chimneys, form, or are born, as human beings, who get dressed and walk to their bunks. Backwards.

Many years later, in 2014, Amis returned to the subject of the Holocaust in a novel called The Zone of Interest. Considered by many, including myself, to be one of the best books of his later years, this time Amis, leaving behind the grimly fanciful irony of the earlier book, focuses on the Sonderkommando, Jewish prisoners who were forced by the Nazis to assist in the disposal of the corpses of their fellow Jews killed in the concentration camps. About this horrifying existence—itself a kind of reverse of what one would expect if one didn’t think too hard about the camps—Amis writes, from the point of view of Szmul, a main character and Sonderkommando:

“Either you go mad in the first ten minutes,” it is often said, “or you get used to it.” You could argue that those who get used to it do in fact go mad. And there is another possible outcome: you don’t go mad and you don’t get used to it.

That passage is one of my favorites, not just by Amis, but by anybody. Although he was known for his explosive, energetic prose, those three sentences above distinguish themselves by not being, in terms of literary fireworks, all that explosive, while also sounding like no one but Amis could have written them. It lays out in plain language the three possible internal reactions for someone forced at gunpoint into the life of a Sonderkommando, with the third possibility, of being fully aware and conscious of what was happening around you and what you were doing, sounding like a bullet would be preferable. The understatement is magnificently effective, because it makes the reader stop and consider what that must be like. Martin Amis hasn’t told you anything but the basics, and now you’re forced to sit there and think about it.

One of the clichés in the life of Martin Amis is the arc of his career, from early success and recognition, until he became a “brat” who demanded too much money for his book contracts. (Worse still for some, he was the son of Kingsley Amis, who was not only a famous, and great, writer himself, but one whose politics drifted further right the older he got, thus throwing a suspicious cloud over the younger Amis’s writing.) And not only did he not deserve the money, some said, but he couldn’t even back it up with work that might meet his, apparently forgotten, former high standards. I say “Nuts!” to all of that. I will grant you that two of his worst novels, Yellow Dog and The Pregnant Widow, were written during the latter half of his career, but even those aren’t disposable. The Pregnant Widow has a great beginning, at least, and Yellow Dog is so odd that I still find myself thinking about it twenty years later and wanting to go back to it to see what I missed. Plus Amis’s later years also boast the excellent House of Meetings and Inside Story, apparently his final novel, an autobiographical work of the sort of meta-variety (all the major players—Martin and Kingsley Amis, Christopher Hitchens, Philip Larkin—appear under their own names) which is primarily about his friendship with Hitchens and the grief he felt over his friend’s death. Inside Story also features chapters about prose style, and, most entertainingly, how to write (there are some genuinely useful tips in there, by the way). He ends one such chapter, called “How to Write: Impersonal Forces,” after discussing when to use “was” or “were,” like this:

And which is it? . . . That question has inspired huge volumes of linguistic philosophy, full of graphs and equations. No doubt it is all nauseatingly complicated. I stick to a simple rule. If I’m writing in the present tense I use it, and if I’m writing in the past tense I don’t. So it’s she wishes she were and it’s she wished she was. The present can go either way. The past is settled. I really think that’s all you need to know. He wishes his friend were alive. He wished his friend was alive. Is that at least reasonably clear?

Like that passage from The Zone of Interest, this isn’t exactly funny. Perhaps as the weight of years increased, Amis found himself laughing less. But, especially now that he’s gone, Martin Amis’s reputation will primarily rest with that early rush of funny, acidic, exquisitely literate novels (I’ll leave his acting role as the kid who dies halfway through the 1965 film of A High Wind in Jamaica for another writer to deal with) that, for at least a span of several years, beat back claims of what Amis called “cronyism,” as the son of a writer who had to prove himself. This is at least mildly funny, when you consider how different Kingsley and Martin were in their subject matter, and especially their style. Kingsley once said of his son’s prose that he wished Martin would write more sentences like “Then they finished their drinks and left.” Martin, meanwhile, felt that Kingsley’s prose had altogether too much of that kind of thing, and, in any case, he, Martin, was not interested in writing a sentence, any sentence, that just anyone could write.

And so he proved time and time again, starting right at the beginning, with his first novel The Rachel Papers. That book, the most mainstream of all his novels, came out in 1973 (and was subsequently plagiarized by Jacob Epstein, the son of one of the founders of the New York Review of Books, in his book Wild Oats; of this situation, Amis said “Epstein wasn’t influenced by The Rachel Papers, he had it flattened out beside his typewriter”) and was followed by a series somewhat mysterious but definitely Amisian novels: Dead Babies (1975), Success (1978), and Other People (1981).

And then there was Money. Until the publication of Money in 1984, Amis hadn’t had much of an impact on the Literary World, American Division (it was almost a decade before Success was published in the States), but this novel, featuring the financially obsessed John Self as our unpleasant protagonist, changed all that. Self directs commercials in England, but now finds himself directing a feature film of his own devising in New York City. He’s also a cheap little rat, wallowing in the money he has, spending it all on booze and women and things such as this. Of Self’s trip to a liquor store, Amis writes:

As I tarried in the malt-whiskey showroom an old head presaged by spores of woodrot breath came rearing up at me like a sudden salamander of fire and blood. Dah! In his idling voice he used distant tones of entreaty and self-exculpation, pointing to the recent scar that split his heat-bubbled cheek. No you don’t, pal, I thought—you can’t beg in here: it makes all kinds of unwelcome connections.

Self, you may have gathered, traipses through life at best only vaguely aware that self-awareness is a thing that one might possess. That changes a little by the book’s end, but just a little. Even so, he tries to better himself by taking up reading:

As I’ve already mentioned, 1984 and I were getting on famously. A no-frills setup, run without sentiment, snobbery or cultural favouritism, Airstrip One seemed like my kind of town. (I saw myself as an idealistic young corporal in the Thought Police.) In addition, there was the welcome sex-interest and all those rat tortures to look forward to. Stumbling into the Ashbery late at night I saw with a jolt that the room I had hired was Room 101. Perhaps there are other bits of my life that would take on content, take on shadow, if only I read more and thought less about money.

For a writer capable of coming up with the phrase “like a sudden salamander of fire and blood” to describe the appearance of an alcoholic beggar—which ends up telling us a lot more about the narrator than it does the beggar—falling back on easy prose, the comfortable cliché, must have seemed like a betrayal to his art. And at least once, Martin Amis unloaded both barrels on a popular novel that he felt was insultingly simplistic. The novel was Hannibal by Thomas Harris, and his review was published in Talk magazine back in 1999 (it is now more easily found in Amis’s nonfiction collection The War Against Cliché). And this isn’t Amis being a snob; he says in the review that he absolutely loves both Red Dragon and The Silence of the Lambs. Mainly, though acerbically, he’s mourning the apparent loss of the writer who wrote those books. Amis was especially offended by all the praise Hannibal, ultimately a rather controversial novel, initially received. “The publication of Hannibal back in June,” Amis writes, “cut the ribbon on a festival of stupidity.”

In the US the critical consensus was no more than disgracefully lenient. In the UK, though, the reviews comprised a veritable dunciad. There were exceptions. . . . Elsewhere the book pages all rolled over for Dr. Lecter. I sat around reading long lists of what Hannibal isn’t (“a great popular novel,” for instance), long lists of what it doesn’t do, long lists of what it never get close to pulling off or getting away with. The eager gullibility felt sinisterly unanimous. Is this the next thing? Philistine hip? The New Inanity?

It’s a withering review, one which I could quote from endlessly. Amis titled his review “Bob Sneed Broke the Silence,” which is a line from the novel, only because another reviewer claimed Hannibal did not contain “a single ugly or dead sentence.” So basically, Amis had had it up to here.

Martin Amis was 73 when he passed away last Friday. When Kingsley Amis died in 1995, he, too, was 73. Martin Amis’s best friend, Christopher Hitchens, died in 2011 of esophageal cancer; this same disease claimed Martin Amis. These ultimately meaningless connections still have a way of unsettling a person, troubling them needlessly. It’s the sort of state of mind that a Martin Amis character who is too foolish, or too self-absorbed, or simply unable to relax for half a second, might find themselves in. But Amis would make it funny. I can’t quite manage that today.