Two Opposing Models of Leadership

In Trump’s second impeachment trial, one key senator showed why he’s a creature of the past while one congressman showed us the future we need.

At the end of it all, you just wanted to take a breath.

It’s over.

In the long-expected and yet still disappointing conclusion of the Senate impeachment trial, a bipartisan majority of 57 senators, short of the 67 needed for conviction, found Donald Trump to be the insurrection-inciting despotic demagogue the facts showed him to be.

Sure, there are those whose lips are so firmly attached to the money trench Trump has at his command they could never have voted to convict him. But they know the truth.

The world knows.

It is my belief that Trump will never be president again. He is damaged and divisive, and while his base remains loyal, he is nationally unliked and has lost the popular vote in two elections. But there are many people who supported him from within his administration (such as Mike Pompeo and Nikki Haley) and in the Senate (such as Josh Hawley and Ted Cruz) itching to try to use Trump’s base to launch a presidential run—which all but guarantees the continuing relevance of Trumpian politics.

To break out of the mindset that has dominated national politics since the Gingrich era—that politics is a hyperpartisan zero-sum game, an attitude that contributed to the rise of Donald Trump—we need politicians more dedicated to the republic than to their personal power.

Two men I’ve known the longest in Congress and who played prominent parts in the recent Senate trial and its outcome are indicative of what I mean. One represents what we can no longer tolerate. The other represents what we need.

Yes, one is a Republican and one is a Democrat. But what really separates them is where each stands in terms of caring about and acting in the public interest. They are at opposite ends of the spectrum.

At one end you have Mitch McConnell, who, though he loathes Donald Trump, voted to acquit him. He did this because he wanted to maintain control of the GOP and feared he would be minimized by Trump’s supporters if he voted otherwise.

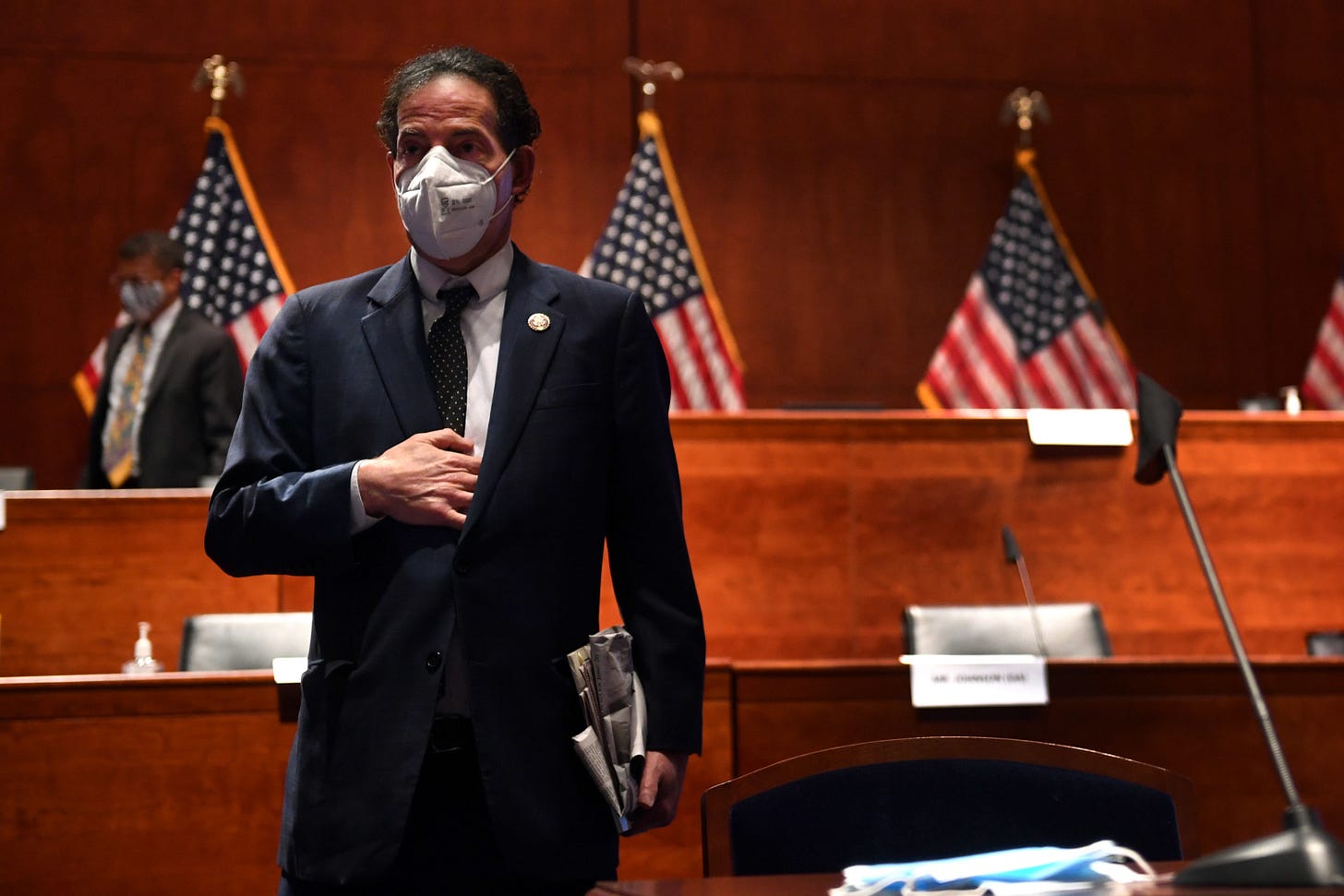

At the other end you have Jamie Raskin, a relatively new face in the House who beat the odds to become a member of Congress and then, despite an extreme personal tragedy, put together a devastating case against Trump.

Mitch McConnell started his political life playing the same games he plays today. He was a ruthless opportunist who sought to overthrow the leadership in the Kentucky GOP in the 1960s, failed, and became a “moderate” Republican to win election as the county judge/executive in Jefferson County (Louisville) before he was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1984.

His shift that year was remarkable. Roger Ailes put together a duplicitous ad campaign that helped McConnell come from 40 points behind in the polls to win. His was the only Senate seat the GOP picked up in Ronald Reagan’s 1984 landslide election. Over time, McConnell dropped any pretense of being a moderate as he followed the money further and further to the right.

In 1978, the night before my first interview with McConnell, I spoke with someone who knew him well—an uncle who had worked with him in the Jefferson County Republican party. “The thing you have to remember about Mitch McConnell is he’s about only one thing,” I was told. “What’s that?” I asked.

“Mitch McConnell is always and only about Mitch McConnell.”

For nearly a half century those watchwords have helped me understand McConnell. They explain why he does what he does. Sure, he’s smart and knows how to count votes—and that explains how he can do what he has done. But to understand the why, you need to understand that for McConnell it is all about power and personal gain.

When Trump marched McConnell out to the Rose Garden in 2017 and appeared to have him on a leash, one could see the senator chafing at having to play nice. But McConnell wanted a slew of judges appointed to federal courts across the country, and to get his way he smiled at Trump.

It was never that McConnell sold his soul to Trump (he didn’t have one to sell anymore). It’s that McConnell played Trump. McConnell’s weakness has always been that he will do anything to stay in power and anything to get what he wants—even slow-walking the impeachment trial of a man he despises so it couldn’t begin until Trump was out of office, and then voting to acquit him.

Of course, McConnell tried to have it both ways. He tried to protect his reputation among Trump supporters, especially those in Congress, by voting to acquit. Then he tried to give the impression of caring about his institution by making a floor speech lambasting Trump for his actions during the insurrection. That earned him a sharp rebuke from Trump yesterday. “Mitch is a dour, sullen, and unsmiling political hack, and if Republican Senators are going to stay with him, they will not win again,” Trump declared. The cannibals have begun to devour each other.

Then there’s Jamie Raskin. When I first met him 15 years ago, he was a law professor at American University and a new member of the Maryland state legislature. Representing parts of Silver Spring and Takoma Park, he was also very active in assisting the newspaper members of the Maryland, Delaware, District of Columbia Press Association in keeping newspapers viable.

He introduced a medical marijuana bill that Governor Martin O’Malley signed into law. He fought for a variety of issues, including legalizing same-sex marriage in Maryland.

When longtime congressman Chris Van Hollen decided to run for the Senate in 2016, Raskin was one of nine Democrats vying for Van Hollen’s vacated House seat. Kathleen Matthews, formerly a fixture of local TV news, led the polls for months. Raskin was either a distant second or a close second, depending on the poll. Then David J. Trone, a Maryland businessman, entered the race and tossed enough money into it to make it the most expensive House race in history. Raskin was heavily outspent by both Matthews and Trone.

What saved Raskin was his base of supporters and his public appearances. I hosted candidate forums during this race and Raskin remained remarkably steady, calm, and rational even when others got emotional. Trone, who didn’t like how long one of the candidate forums was going, signaled to me with his watch that I should wrap it up. When the Washington Post pointed this out, Trone started to tank in the polls, but he took enough of Matthews’s votes that Raskin won.

Since then Raskin has worked across the aisle and gained a reputation in the House as professorial and collegial. In 2017, he cosponsored a bill to protect journalists (a national shield law) with Republican Jim Jordan—and Jordan, who never says nice things about Democrats, was effusive in his praise of Raskin and their collaboration.

Raskin, in short, is just the opposite of McConnell. He remains the rarest of congressmen—logical, practical, and smart.

On January 5, the day before the storming of the Capitol, Raskin faced the unthinkable task of burying his son, whom he lost to depression. Yet in the aftermath of the attack, Raskin never shied away from doing his job—even though no one would’ve faulted him had he decided to sit out the second impeachment.

He put the needs of the republic ahead of his own needs—which makes him exactly the sort of lawmaker and leader the country needs going forward.

Mitch McConnell is among the most selfish and irresponsible men ever voted into office. He is a symbol of the past, an emblem of a broken political structure—of how partisan and petty personal concerns can destroy the United States.

Raskin is the hope for the future—putting the country first, even putting it above personal concerns.

Those are the kinds of actions it will take to save our republic.