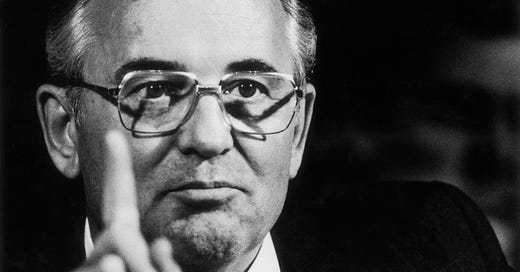

Mikhail Gorbachev, 1931–2022

The last Soviet leader’s record is more complicated than conventional wisdom suggests—but he was ultimately on the side of freedom.

Looking for symbolic meanings in current events always carries the risk of reaching for facile or far-fetched interpretations. And yet it’s difficult not to see symbolism in the fact that Mikhail Gorbachev, the first and last president of the Soviet Union, died just a few months after the final death agony of the new Russia that he had, not always willingly, midwifed: a Russia of free travel and free speech, of McDonald’s restaurants and Adidas shoes, of openness to Western culture and Western values; a Russia that aspired to join the global community of liberal democracies.

By the time of his death this week at the age of 91 following a long illness (reportedly kidney ailments), Gorbachev had become a relic of a distant past. Yet for a while, he was a global star; in 1988, he even made it on Gallup’s Top Ten Most Admired Men list, one of the very few non-American men to have that distinction and the first Soviet man to appear on it since its introduction in 1955. Rush Limbaugh coined the term “Gorbasm” to mock the transports of delight with which America’s liberal intelligentsia greeted Gorbachev, and on that occasion the right-wing radio jock was on to something. But Gorbymania was not just an American or left-wing phenomenon; it swept up even a Cold Warrior like Margaret Thatcher. (A little-known fact: the Iron Lady made her famous remark, “I like Mr. Gorbachev. We can do business together,” in late 1984, when the future superstar was only a rumored heir to the USSR’s top leadership.)

Partly, the Gorbachev love had to do with his Nobel Peace Prize-winning role in ending the Cold War during a decade when Western consciousness was haunted by fears of a nuclear holocaust. (The early 1980s were the time of nuclear terror at the movies: The Day After, WarGames, Testaments.) But Gorbachev was seen as the harbinger of freedom and change as much as peace, bringing fresh air to a country and a system that had seemed trapped in eternal moribundity. His ascent to general secretary of the Communist Party of the USSR in March 1985 came after an extended gerontocratic Weekend at Bernie’s for the country’s leadership: the pathetic final years of a visibly ill, speech-slurring, not-quite-there Leonid Brezhnev and then the quick succession of two rulers, Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko, who each died after barely a year in office. (“My problem for the first few years was they kept dying on me,” Ronald Reagan quipped—while the underground Soviet humor mill came up with a joke in which a man gets a season pass for Kremlin state funerals.)

A vigorous 54-year-old, Gorbachev not only promised change but seemed to embody it: confident, energetic, and, well, alive—and not just in the sense of being able to move and speak. Here was Soviet leadership with a human face: As Russian writer and commentator Ilya Milshtein wrote twenty years later, it still remains a mystery “how, under such a foolproof negative selection system as the Soviet Politburo, a man with such a face could come to power..” He was so human that he even had a visible wife, Raisa, an elegant and accomplished woman who openly traveled abroad with her husband, breaking the tradition of Soviet leaders’ wives staying in the shadows.

It is something of a truism that Gorbachev intended to reform and strengthen the Soviet system through his perestroika (restructuring) but in the process unchained forces that led to its collapse. And indeed, there is little doubt that he did not intend radical reform, let alone the regime’s undoing. His early moves were reminiscent of his onetime mentor Andropov, the former KGB chief whose own attempt at reform—geared toward efficiency, not liberalization—was cut short by kidney failure in 1984. Like Andropov, Gorbachev drastically curbed alcohol sales to combat rampant drinking—generating a slew of jokes and limericks that had him getting pummeled by angry boozers—and took other steps intended to boost productivity. Uskorenie (“acceleration” of economic and technological modernization) was the Gorbachev-era motto before glasnost (“openness”).

Politically, Gorbachev’s beginnings weren’t particularly liberal, though one could obviously counter that he could not afford to show liberal leanings right away. Still, it took him nearly two years—until December 1986—to release the great scientist and human rights activist Andrei Sakharov and his wife, Elena Bonner, from internal exile in the city of Gorky (now Nizhny Novgorod), where they had been confined in 1980 for Sakharov’s protests of the Soviet war in Afghanistan. Around the same time, human rights activist and author Anatoly Marchenko died in a prison hospital after a three-month hunger strike seeking the release of all Soviet political prisoners. It was only six months later, in June 1987—following an international outcry over Marchenko’s death—that Gorbachev announced the first large-scale amnesty of Soviet prisoners of conscience: people sentenced for “slander against the Soviet system” or for violating laws restricting religious practices.

In the same year, glasnost and democratization became official policy. Their ostensible purpose was to enable discussions that would point the way to a better socialism and restore the “true,” lofty Leninist principles of the Bolshevik revolution. As Milshtein put it, “[Gorbachev] believed that combining the best features of Lenin's immortal teachings with the living experience of the rest of the world would get the empire out of its dead end.”

Yet keeping the conversation and debate within the narrow bounds of the permissible turned out to be an impossible challenge. While the vaunted economic and technological “acceleration” never happened, political liberalization did accelerate—at warp speed. Soon, Soviet periodicals were featuring articles that questioned socialism itself, such as “Who’s Got the Fatter Pies,” a short essay by “Lаrisa Popkova”—later identified as the free-market economist Larisa Piyasheva—published in the prestigious monthly Novy Mir in May 1987, arguing that only a market economy could ensure abundance and that it was time to give up the quest for “true” socialism. Other publications assailed the Revolution and not only documented Joseph Stalin’s monstrous crimes but stripped the halo away from Vladimir Lenin.

By 1990, literature whose possession was once enough to send a Soviet citizen to prison, such as The Gulag Archipelago, was being published and openly sold in the USSR. Russian media began to tackle once-taboo topics such as poverty, homelessness, crime, and the abysmal state of housing and medical care in the “workers’ paradise.” Hard-hitting television programs sprung up: investigative reports and live, unscripted talk shows with on-air calls from viewers. Grassroots political activism reared its emboldened head.

By the spring of 1989, there was clamor not just for reform but for regime change—and in particular, for the repeal of Article 6 of the Soviet Constitution, which stated that the Communist Party was a “governing and guiding” force in Soviet society and the “nucleus” of the Soviet political system. At first, Gorbachev adamantly opposed such a move (bitterly clashing with Sakharov, by then a member of the Congress of People’s Deputies). Then, in early 1990, he flip-flopped, very likely because of a groundswell of public protest including a million-strong rally in downtown Moscow. In March 1990, Article 6 was changed to acknowledge the role of “other” parties and organizations alongside the Communist Party; while this was obviously not an equal playing field, it was, at least, a field with more than one player.

While the clamor for radical reform, freedom, and a life of dignity was growing in Russia, other Soviet republics and Eastern bloc countries were increasingly in open rebellion against Soviet rule itself, with massive protests filling city streets. On three occasions—in Tbilisi, Georgia on April 9, 1989; in Baku, Azerbaijan on January 20, 1990; and in Vilnius, Lithuania in on January 13, 1991—Soviet troops attacked demonstrators, killing 14 people in Vilnius, 21 in Tbilisi, and 133 in Baku. But the protesters were not intimidated, and the repressions did not escalate. In Berlin, the protests led to the fall of the Berlin Wall, a little over two years after Reagan’s famous challenge: “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.”

In August 1991, Gorbachev—who by then held the newly created office of president of the USSR—was ousted by a hardliners’ coup; the plotters placed him under house arrest while he was on vacation in Crimea after he refused to cooperate with them. One often-forgotten detail of this rather farcical coup is that its goal was to prevent the replacement of the Soviet Union by a “Union of Soviet Sovereign Republics,” with a drastically downscaled but still existent federal state. Three days later, the coup was defeated, partly thanks to the leadership of Gorbachev’s protégé-turned-rival Boris Yeltsin, recently elected president of Russia. After his return to Moscow, Gorbachev was still hoping to rescue USSR 2.0. But it was too late: The new agreement of ex-Soviet republics established a Commonwealth of Independent States with no common government and no president. On December 25, 1991, Gorbachev’s post ceased to exist along with the Soviet Union.

Debates over the extent to which Gorbachev deserves credit for the collapse of Soviet communism will no doubt continue for some time. Guardian columnist Jonathan Steele writes that Gorbachev “could have remained in office for years had he not chosen the path of reform” and that, while the system was not running very efficiently, it was nowhere near breaking down. People who actually lived in the Soviet Union at the time took a different view: As far back as 1970, some were wondering if the Soviet Union would survive into the mid-1980s. The satirist Viktor Shenderovich has described the late 1980s as “that time when the Soviet state still existed, but the food had already run out.” Or, as the late novelist Vladimir Voinovich wrote in a 2011 tribute to Gorbachev on the latter’s 80th birthday:

By the 1980s, life in the USSR had become unbearably squalid and dreary. Shortages of everything: sausages, laundry detergent, toilet paper, and so on. People spent as much time in lines as they do in traffic jams today. Prohibitions on everything: no jeans, no break dancing, no samizdat, no foreign radio. The realization that one could not go on living like this was taking hold of the masses and finally reached some Politburo members, including Gorbachev.

Obviously, no one will ever know what would have happened with a different leader at the helm. As per Voinovich, Gorbachev certainly wasn’t the only one who believed that change was necessary; it’s highly likely that any change which involved more decentralization and a freer exchange of information would have acquired a momentum of its own and would have eventually spun out of control. In any case, once the liberatory forces were unleashed, with demands for independence in the Soviet republics and for true democratization and economic reform in Russia, Gorbachev chose the self-defeating strategy of stubbornly opposing radical change—i.e., any change that would dismantle the power of the Communist elite—until such change could no longer be stopped, at least not without massive bloodshed. He opted against bloodshed; but he also ended up looking like a weak ruler who had tried and failed to assert his will.

Gorbachev, of course, had a much happier ending than either Nicholas II or Louis XVI, both of whom had a similar dynamic with revolutionary forces. Despite occasional slights and humiliations at the hands of the post-Soviet Russian state (at one point, he was locked out of the offices of the Gorbachev Foundation due to a dispute with the government over office space), he was treated as a respected elder statesman abroad. He was in demand as a speaker at conferences and on college campuses, published books, and made Pizza Hut and Louis Vuitton commercials. In Russia, he was generally despised by Communists, Russian nationalists, and liberals alike, for various reasons; when he tried to run for president of Russia in 1996, he got less than one percent of the vote.

Russian dissidents had a complicated relationship with him. Some, including Voinovich, believed that “Gorby” deserved great credit for his decision not to suppress popular protest by force and hold on to power through violence and terror. The same view was taken by Sakharov’s widow Bonner, with whom he had a prickly relationship, and by the late Valeria Novodvorskaya, who was once arrested during the Gorbachev era for publishing an article titled “Heil, Gorbachev!” in her party’s newsletter. “Gorby didn’t like blood, and one could buy freedom from him at a reasonable price,” Novodvorskaya wrote in 2011. “Tanks stopped and shovels dropped when he could see that people were willing to brave death.”

Others were less forgiving. The late Soviet dissident Vladimir Bukovsky tried to seek a criminal prosecution against Gorbachev during the latter’s trip to London on 2011 on charges related to the civilians deaths in Tbilisi, Riga, and Vilnius; he was unsuccessful, and even most of his fellow ex-Soviet dissidents disapproved, arguing, among other things, that it was unclear whether Gorbachev ordered or even knew about the violent crackdown in any of these instances. Gorbachev’s detractors have argued that it’s obscene to credit him for not killing more people or for giving people freedoms that were theirs by inalienable right. Which is fine from the standpoint of moral absolutism, but doesn’t work so well with regard to real life.

An article published two years ago on Gorbachev’s attempts to protect the Communist Party’s monopoly on power contained some remarkable excerpts from the minutes of Soviet Politburo meetings in February and March 1990. In those passages, Gorbachev railed against the pro-democracy opposition and complained that “scum” and “immoral people” had “seized a monopoly on TV.” He even snarked, in rather Putinesque language, that “we’re playing nice” and “we ought to smack them in the face.” And yet, for all this griping and for all his Soviet instincts, Gorbachev in fact did not lift a finger to curb the new media freedoms and deprive his “immoral” opponents of a platform. Is it wrong to praise him for that? Well, just look at the alternatives.

And so I’ll go with Bonner, who told the Russian newspaper Kommersant in 2001 that she regarded Gorbachev as the ruler who had done the most good for Russia because, in spite of all his flaws, errors and blind spots, he “succeeded in breaking up the Soviet totalitarian system which seemed eternal.”

On a personal level, I vividly remembered the energy and exuberance of the Gorbachev years that I saw on my trips to Moscow in 1990 and 1991. There were hardships, to be sure; but there was also hope and discovery. The protest marches, the conferences and meetings where people excitedly discussed political ideas, the once-forbidden books and movies, the religious and cultural freedom (there was a Jewish theater! in Moscow!); the beginnings of a consumer culture; even the fact that, strolling along Moscow’s Arbat avenue, you could run into a person fearlessly selling a typewritten booklet of Gorbachev jokes and another offering to take your picture with a very lifelike Gorby cutout. Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive, as Wordsworth once said about the French Revolution—and yes, we know how that turned out, too.

This doesn’t mean I’m on the Gorbachev adulation bandwagon. Politically, his post-presidential legacy was uneven; he backed Vladimir Putin on the Crimea annexation and sometimes seemed to blame the “arrogant” West for Russia’s intransigence, but he also repeatedly criticized the Putin regime for rolling back democratic freedoms. (He made no public comment on the invasion of Ukraine, which happened when he was no doubt already severely ill; but his longtime friend Aleksei Venediktov, until recently editor-in-chief of the now-shuttered Ekho Moskvy radio station, told Forbes Russia that he was “naturally upset” and that all of his accomplishments, especially in the area of civic freedoms for Russians, had been reduced “to zero, to dust, to smoke.” It is unclear, however, whether Venediktov was quoting Gorbachev’s actual words.)

Some of Gorbachev’s observations about the West could come across as smug: When I heard him talk at the Wilson Institute’s Kennan Center at the start of the Obama era, he asserted that America needed a perestroika of its own (which I thought was a rather facile equivalency) and also offered that he knew America “very well” from his speaking tours, mostly on college campuses—seemingly unaware of what a narrow slice of American life that was, or of how limited his communication was by the fact that he spoke no English. And yet he also came across as a man of genuinely good will, in a way that didn’t feel like an act—just as it didn’t feel like an act when he told New Times editor Yevgenia Albats in 2016 that his creed was, “No blood,” or that he was ultimately “a man of freedom”: “Freedom of choice, freedom of religion, freedom of speech; freedom, freedom—let them shoot me but I’m not going to renounce that.” Or when he wrote a warm letter to Bonner on her 85th birthday, expressing the hope that their shared ideals—“a democratic Russia, the rule of law, a more just world”—would someday be realized.

This was not mere posturing: Milshtein reports that in 2000 Gorbachev quietly, without fanfare, came to see Putin at the Kremlin to put in a word against attempts to censor the NTV television network.

His lifelong love for his wife Raisa, who died of leukemia in 1999, felt just as genuine; he spoke of her with palpable warmth and poignancy in the 2016 interview with Albats.

Gorbachev’s death underscores the passing of an era. Over the years, people who evaluated his role in Russia’s history often remarked (as did Novodvorskaya, for example) that despite Putin-era backsliding toward authoritarianism, the habits of freedom Russian people had learned during the Gorbachev years—being able to read whatever they want, for example—could not be lost. Unfortunately, in 2022, even that seems in doubt.

And yet Gorbachev’s career is also a reminder that history is unpredictable. Is this the end of the road for freedom in post-Soviet Russia—or perhaps an incredibly dark moment before a new beginning?